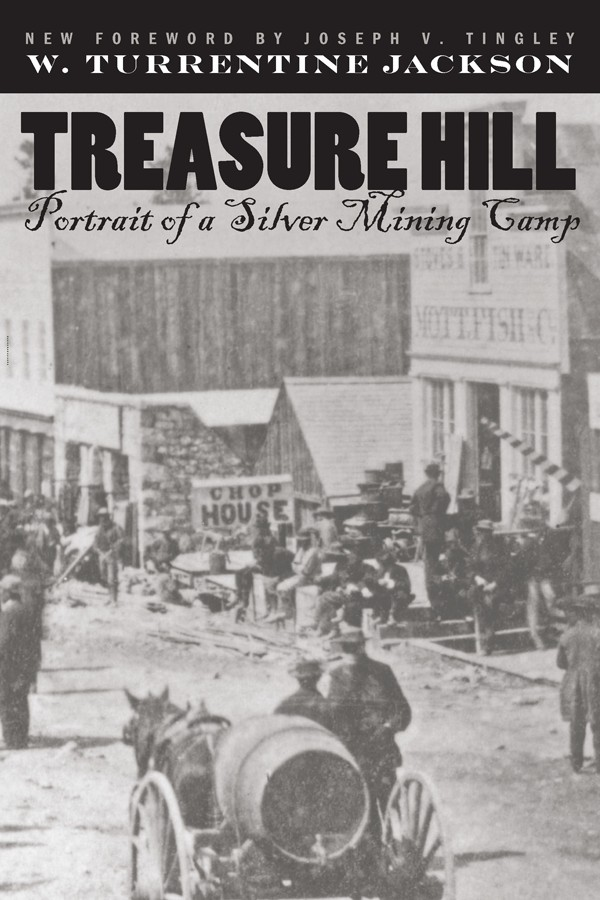

Treasure Hill: Portrait of a Silver Mining Camp was first published by the University of Arizona Press in 1963.

It is reprinted by arrangement with the author.

University of Nevada Press, Reno, Nevada, 89557 USA

Copyright 1963 by The Board of Regents of the Universities and State College of Arizona

Foreword copyright 2000 by University of Nevada Press

Manufactured in the United States of America

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Jackson, W. Turrentine (William Turrentine), 1915

Treasure Hill : portrait of a silver mining camp / W. Turrentine Jackson ; with a foreword by Joseph V. Tingley.

p. cm.

Originally published: Tucson : University of Arizona Press, 1963.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN: 978-0-87417-361-1

1. Frontier and pioneer lifeNevadaWhite Pine County. 2. Mining campsNevadaWhite Pine CountyHistory. 3. Silver mines and miningNevadaWhite Pine CountyHistory. 4. White Pine County (Nev.)History, Local. 5. White Pine County (Nev.)Social life and customs. 6. White Pine County (Nev.)Social conditions. I. Title.

F847.W5 J3 2000 979.315dc21

00-008004

This book has been reproduced as a digital reprint.

ISBN-13: 978-1-943859-16-0 (electronic)

FOREWORD

W. Turrentine Jacksons Treasure Hill is more than the story of a solitary mining camp; it is the account of the short life-span of an entire mining district. Jacksons work was the first historical account of the White Pine rush, and it remains today the only study of the frantic activity set into motion by the silver discovery high in Nevadas White Pine Range. There are a few descriptions of the mines and the geology of the district in technical publications, but these by their very nature do not tell the human side of the White Pine story. Jackson makes heavy use of contemporary newspaper accounts to tell his story, and he methodically covers each aspect of mining-camp life, from community water problems to competition between rival stage lines to provide passenger and freight service to the isolated communities of the district. He tells of visiting theatrical troupes, camp-wide epidemics, and the constant search for more silver ore. Jackson documents this search for ore, the sad endpoint of almost every mining camp anywhere, in his account of the Eberhardt and Aurora Mining Company, the London company that entered the district in 1870 after the boom was over and for the next fifteen years persistently invested in a fruitless search for ore.

The boom-bust cycle of mining was played and replayed throughout the American West in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Discoveries were made and mining camps grew up around them in California, Nevada, Idaho, Montana, Colorado, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, and even in Alaska and Canadas Yukon. Some of these camps, like Virginia City, Nevada, grew into permanent towns, while othersmost othersflashed up for a few years, then passed on to be forgotten. At even the best of the camps, the mines didnt last that long. The best ore found on Virginia Citys Comstock Lode was mined out within twenty years of the Lodes discovery in 1859. Mining limped on at Virginia City until the mid-1900s, but the town was really in decline after 1880. Other Nevada camps suffered similar fates. Austin, in the Reese River District, flourished between 1863 and 1887, a period of only twenty-four years. Unionville, in the Humboldt Range, was discovered in 1861, peaked in 1864, and was on its way out by 1880. Pioche and Bristol in Lincoln County, Belmont in Nye County, Tuscarora in Elko County, and Taylor in White Pine County all flourished during the short period between 1860 to 1870 and 1880. Records of the time show that each of these camps produced silver for fifteen to twenty-five years, then faded.

Some mines closed because of the low price of silver. Priced at about $1.33 per ounce since 1850, silver in 1873 began a slide that took it below $1.00 per ounce by 1886 and down to 60 cents per ounce by the turn of the century. This caused economic crises in mining camps throughout the West.

The most commonly recurring theme of decline in the mines, however, was simply the lack of ore. The high-grade, enriched silver ore found near the surface in many of the camps was quickly mined out, leaving only subeconomic roots to be followed by die-hard miners. Rarely could these low-grade remains be mined profitablyat that time, equipment and mining techniques had not been developed for what we now refer to as bulk mining, and open-pit mines were not known.

White Pine, the isolated mining district located on the side of Treasure Hill in a still-remote area of east-central Nevada, perhaps best represents the mining camp of the nineteenth-century West. Even in a time of boom camps with short life-spans, White Pine was an anomaly. It could have been like any other camp in the Mountain West, but it turned out to be one of the richest and shortest-lived of them all. The entire community structure was built in a little over one year, as if the rarified air at the near-9,000-foot elevation of White Pine caused the progression of life in the camp to accelerate. Discovered in 1867, the best was all over by the end of 1869. During those first three seasons, over $6 million in silver was dug from White Pines mines. The deposits were fabulously rich, most lying within five to sixty feet of the surface. The mineral did not extend to depth, but as in many other western camps, hopeful miners kept searching and digging for years after the bust set in. Nothing like the original bonanza ore was again found, and White Pine quietly died.

When W. Turrentine Jacksons Treasure Hill was published in 1963, the camps of the White Pine District had been ghost towns for almost eighty years. Just the previous year, however, in 1962, a gold discovery was made near Carlin in northern Nevada that set off a new prospecting wave across the state. The Carlin deposit was large, and the gold was invisiblethat is, it could not be seen with the eye or recovered in a gold pan and had been missed by the nineteenth-century prospectors. In the frenzy that followed, every historic gold and silver camp in Nevada was looked over and re-evaluated. White Pine did not escape. A modern geologic study of the district had been published in 1960, and supplemental work in 1970 pointed out that the miners of the 1860s may have looked in the wrong place for more ore. If there were undiscovered silver deposits remaining to be found at White Pine, the deposits would be shallow, hidden under barren rock off to the side of the old mines rather than beneath them where all of the searching was done previously. Also fueling interest, metal prices began to rise. Except for two years during World War I, silver had remained below $1.00 per ounce from the beginning of the century until 1962, when the price rose to $1.09 per ounce. Silver topped $5.00 per ounce by 1978, and during 1980 it averaged slightly over $20.00 per ounce. The price did not stay at that level for long, but it was long enough to bring miners back to White Pine.

By 1977, Treasure City Mines, Inc., had put together over three hundred mining claims in the center of the White Pine District and announced plans to construct a mill to treat eight hundred tons of ore per day from two underground mines and an open pit. Mindful of the water problems that the earlier miners had faced, the new company constructed a 950,000-gallon reservoir at Hamilton to support their planned milling operation. Since only scattered shacks and crumbling foundations remained at the historic camp, an area was cleared above the old Hamilton townsite to park mobile homesthe modern version of a mining campfor company workers. In 1979, the holdings of Treasure City Mines were acquired by the Gold Creek Corporation of Ely, Nevada. The Gold Creek Corporation produced about 1 million ounces of silver from White Pine during 1979 and 1980, almost entirely from old dumps left from the historic mines. Very little of this silver came from new mining. During the same time, Silver King Mines, Inc., another Ely-based company with holdings in White Pine, hauled a few truckloads of dump material to its silver mill at Taylor, east of Ely. In 1983, more work was planned for White Pine by a Canadian company. This time, a heap-leaching operation was visualized that would recover about 250,000 ounces of silver a year from dumps, tailings, and some new ore. Nothing came of this venture, and another company faded from the White Pine scene.