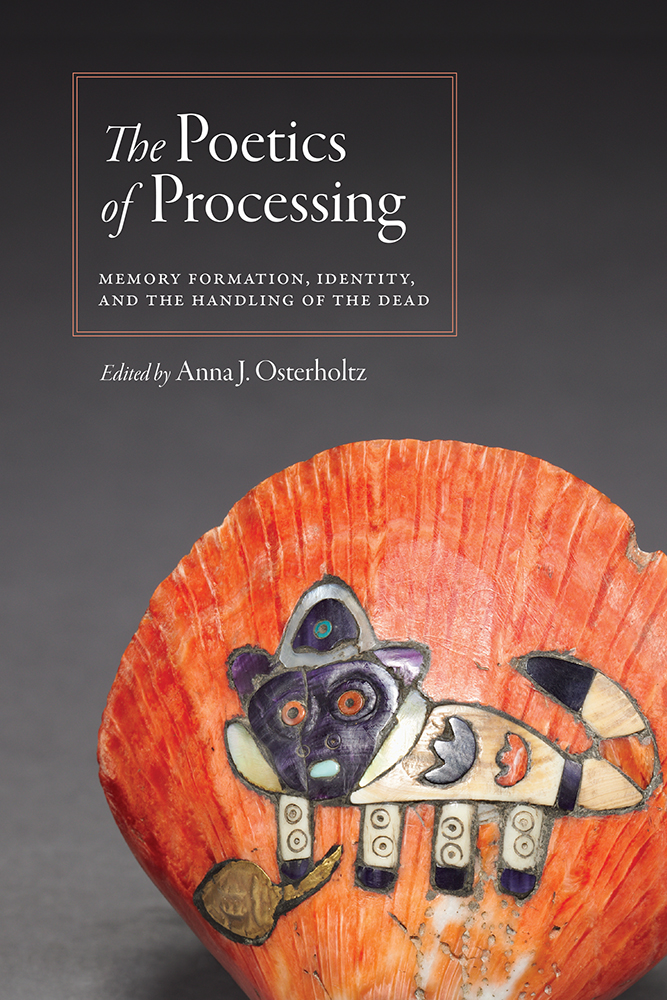

The Poetics of Processing

Memory Formation, Identity, and the Handling of the Dead

EDITED BY

Anna J. Osterholtz

U NIVERSITY P RESS OF C OLORADO

Louisville

2020 by University Press of Colorado

Published by University Press of Colorado

245 Century Circle, Suite 202

Louisville, Colorado 80027

All rights reserved

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of the Association of University Presses.

The University Press of Colorado is a cooperative publishing enterprise supported, in part, by Adams State University, Colorado State University, Fort Lewis College, Metropolitan State University of Denver, Regis University, University of Colorado, University of Northern Colorado, University of Wyoming, Utah State University, and Western Colorado University.

ISBN: 978-1-64642-060-5 (hardcover)

ISBN: 978-1-64642-061-2 (ebook)

https://doi.org/10.5876/9781646420612

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Osterholtz, Anna J., editor.

Title: The poetics of processing : memory formation, identity, and the handling of the dead / edited by Anna J. Osterholtz.

Description: Louisville : University Press of Colorado, [2020] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020028107 (print) | LCCN 2020028108 (ebook) | ISBN 9781646420605 (cloth) | ISBN 9781646420612 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Whitehead, Neil L. | Human remains (Archaeology) | DeadSocial aspects. | Funeral rites and ceremonies, Ancient. | DeathSocial aspects. | Violence.

Classification: LCC CC79.5.H85 P64 2020 (print) | LCC CC79.5.H85 (ebook) | DDC 930.1dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020028107

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020028108

Cover illustration courtesy of The Cleveland Museum of Art

For those whose bodies we excavate,

Whose bodies we learn from,

Whose names are lost,

May your stories be told.

Contents

Anna J. Osterholtz

Beth Koontz Scaffidi

Kyle D. Waller and Adrianne M. Offenbecker

Kristin A. Kuckelman

Debra L. Martin and Anna J. Osterholtz

Dilpreet Singh Basanti

Roselyn A. Campbell

Marin A. Pilloud, Scott D. Haddow, Christopher J. Knsel, Clark Spencer Larsen, and Mehmet Somel

Megan Perry and Anna J. Osterholtz

Christina J. Hodge and Kenneth C. Nystrom

Carlina de la Cova

Eric J. Haanstad

Grave of Susan B. Anthony the day after the 2016 election

Uraca site location relative to Nasca and Huari cultural centers

Petroglyphs from Uraca

Trophy-head fractures

Retouching and reuse

Removal of the ocular tissues

Re-creation of the eyes

Abnormal dental wear

Cloth with procession of figures

Spondylus shell with inlaid feline

Location map of Paquim

Schematic of Burial 44-13

Cut marks on 44H-13 left radius

Cut marks on 44L-13 right radius

Cut marks on 44K-13 left ulna

Cut marks on 44J-13 left clavicle

Pot polish on 44I-13 right femur

Burning on acromion process from adult individual in Burial 44-13

Burning on 44L-13 femur

The northern San Juan region

Three-dimensional reconstruction of Goodman Point Pueblo

Map of Goodman Point Pueblo

Map of Sand Canyon Pueblo

Reconstruction of Castle Rock Pueblo

The Four Corners region

Articulated elbow from Sacred Ridge

Aksum, northern Ethiopia

Stela 2, an Aksumite storied stela

Plan map of Stela Park area

Plan and profile of the Mausoleum tomb

Plan map of the Tomb of the False Door

Sarcophagus burial in the Tomb of the False Door

Hieroglyph depicting an individual being impaled

Location map of sites discussed in text

Group burial from atalhyk

Tombs excavated, 2012 and 2014 seasons, Petra North Ridge Project

Plan and sections of Tomb B.5

Ward hierarchical cluster analysis: carpals, tarsals, phalanges, and patellae

Holden Chapel, Harvard University

Holden Chapel, floor plan prior to 1850 renovations

Sex and age-at-death estimates, Paquim

Domestication and mortuary practices of Neolithic Anatolian sites

MNI for each context, Petra North Ridge tombs

Introduction

Processing and Poetics, Examining the Model

Anna J. Osterholtz

Just as the dead do not bury themselves (Parker Pearson 1999), the dead also do not manipulate or process their own mortal remains. The manipulation of human remains can be seen as a discursive act, communicating cultural information through actions that create social identity and memory. Manipulation of the body embodies symbolism relating to the construction of society, bringing order to the disorder of death, and giving meaning to the change symbolized by death. Though he was discussing violence, Whiteheads poetics model can be applied to this process as well, particularly when we examine processing and body manipulation as socially constructive cultural performance (Whitehead 2004b, 60). This volume arose out of a session organized by Anna Osterholtz and Debra Martin at the 2016 Society for American Archaeology in Orlando, Florida. For the session, we asked the contributors to consider postmortem treatment of the physical body through a poetics lens, to examine body-processing as a mechanism for the recreation of cosmology events and the creation of memory. The creation of processed bodies has the capacity to transform space, ritually close and open spaces, and reinforce relationships between the living and the dead. The session and this volume are focused on the processing of the body, in what ways it occurs, and how the physical body (and its manipulation) is used as a social tool. The contributors also focus on how the living manipulate the dead both literally and figuratively, using the physical and metaphorical transformation of their remains as a mechanism for the creation of social stratification and power.

Whitehead himself examined the role of manipulation of the body as poetic with his exploration of the kanaim complex in Amazonia (Whitehead 2004b), the difference being that his focus is on the violence of the act, not the nature of the body (in that it is dead when the violence happens). This is a shamanistic process involving mutilation of the body. The fluids associated with putrefaction take on specific social meanings depending on the orifice from which they issue. That the victim of this violence is dead is seen as passivity, a lack of desire to stop the violence or mutilation. As Whitehead (2004b, 71) notes, the poesis involved in the idea of kanaim thus refers to the way in which knowledge of and ideas about kanaim are creatively entangled in a wide variety of indigenous discourse-sexuality and gender, modernity and tradition, Christian religion and native shamanism, interpersonal antagonism and kin relationships, and ultimately human destiny and the cosmos.

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of the Association of University Presses.

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of the Association of University Presses.