Material Vernaculars

Objects, Images, and Their Social Worlds

Edited by Jason Baird Jackson

Indiana University Press, in cooperation with the Mathers Museum of World Cultures, Indiana University

Bloomington and Indianapolis

This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

Office of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

iupress.indiana.edu

2016 by Jason Baird Jackson

A free digital edition of this book is available at IUScholarWorks: http://hdl.handle.net/2022/20925.

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

Manufactured in the United States of America

DOI: 10.2979/materialvernaculars.0.0.00

Cataloging information is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-253-02293-6 (cloth)

ISBN 978-0-253-02348-3 (pbk.)

ISBN 978-0-253-02361-2 (e-bk.)

1 2 3 4 5 21 20 19 18 17 16

Jason Baird Jackson

Material Vernaculars: An Introduction

A BOOK SERIES about which I am very hopeful and a collection of scholarly essays that I hope you will engage and profit fromintroducing them both is my task. They are twin hopes twisted like two fibers wound around each other to produce what I intend as a stronger piece of string. Extending the metaphor, I can observe that the techniques by which the worlds peoples produced cordage were among the earliest and most fundamental matters that the then young fields of anthropology and folklore studies concerned themselves with. We often speak of string as a simple thing, but early work in my fields understood its production by varied means and of varied materials as a vital accomplishment and as a widespread human necessity. Around the world, string wasand isthe basis for cultural elaborations of a near infinite sort. Think about fishing nets, home building, bird cages, weaving, bridge-building the list goes on and on, but think also, for instance, of string figuresa classic ethnographic topic if there ever was onewhich can underpin such arts as storytelling and can contribute to such crucial dynamics as the socialization, and the amusement, of children. While my own children are more likely today to be amused by a game or story presented on a mobile phone, theymiddle-class children from the middle of the United Statescan still make a cats cradle, and they learned how to do so informally from peers. That this is so points to one intended purpose for this series devoted to understanding material and visual culture within particular social worlds. Older concerns in the older fields of material culture studies have not stopped being relevant in a world of mobile phones, server farms, and genetically modified salmon. While I have no particular author in mind, the Material Vernaculars series will, I hope, be the perfect series in which a careful, thoughtful, sophisticated study of handmade (perhaps soon, we might say artisanal) string might be published. More generally, the series is intended to extend and renew traditions of material culture study that reach back to the beginnings of the fieldparticularly as manifest in the disciplines of ethnology, cultural anthropology, and folklore studies.

If the series is to be a good home for long-form scholarship on, for instance, local weaving markets or regional vernacular building practices or the making and uses of kites, the series editorial board and I intend though for the opposite to also be true. While there are societies today where locally produced string is made according to local techniquesand the same is true of so many other thingsstring bags, hoop nets, hammocks, woolen blankets, cotton fabric, and so onwe, the people of the twenty-first century, do live in changed material circumstances from those encountered by the ethnographers of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The way that my children can huddle in culturally specific ways with their friends around a mobile phone to play a video game according to informally transmitted norms and in light of local social dynamics is a token of the fact that material vernaculars are by their nature ever changing and thus continuously open to new kinds of investigation and interpretation. Much of the most exciting work in the fields of material culture studies over the past two decades has sought to approach innovative and, in some measure, new material culture values, forms, and practices through innovative research strategies, such as through multi-sited fieldwork, through the study of commodity chains, and through attention to new media, new manufacturing techniques, and new consumption habits. A full accounting of trends and approaches in contemporary material culture studies is beyond the scope of this introduction (Berger 2009; Geismar 2011; Glassie 1999; Lfgren 2012; Miller 2010; Shukla 2008, 383429; Tilley et al. 2006). It is possible to note though that there is something of a disconnect between scholarshipcentered in museums, for instancethat builds on the older scholarly traditions of studying what are now older material forms and their resonances and newer research lines that do not stress these continuities but instead endeavor to find new approaches to the study of new phenomena. This distinction is drawn too starkly, and admirable workers who defy this binary can readily be foundconsider, for instance, Smithsonian curator Joshua Bells work on my two iconic examples: string figures (Bell 2010) and mobile phones (Kemble et al. 2015). But I trust that the distinction and the isolation of these scholarly worlds will be recognizable to my colleagues in ethnology, cultural anthropology, and folklore studies.

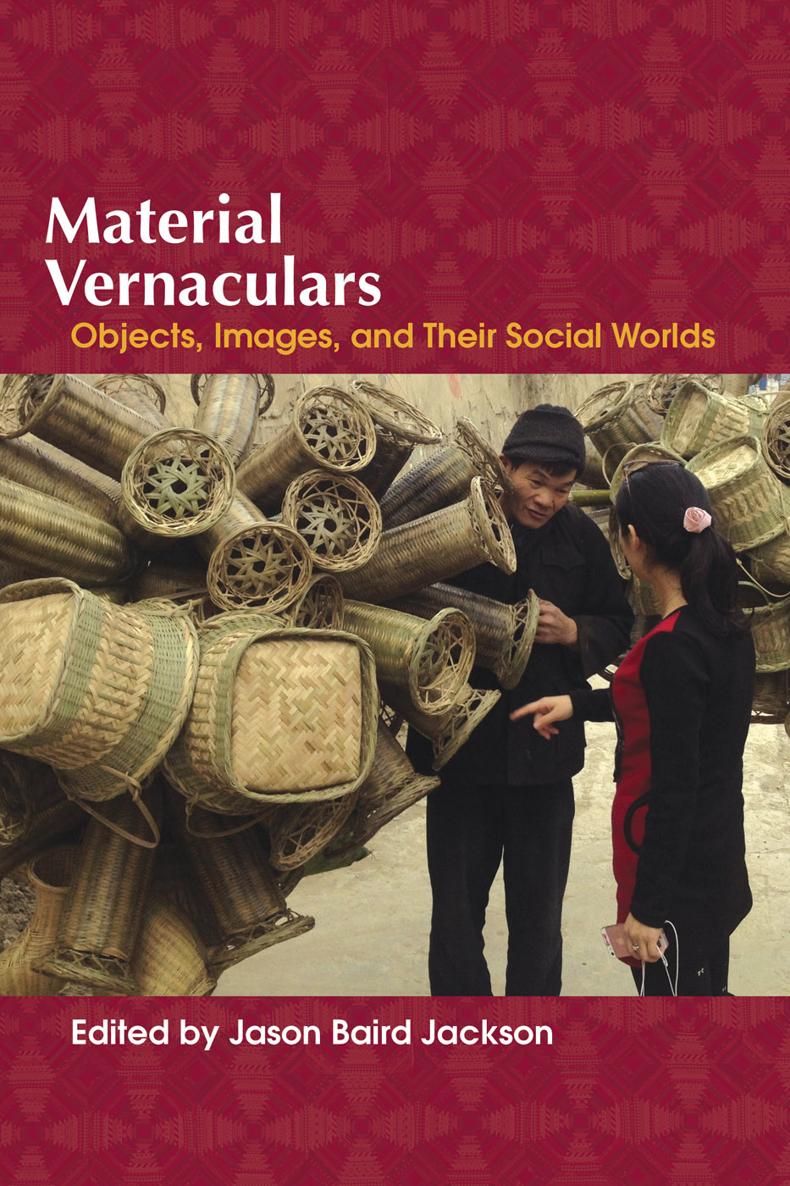

It is my hope that the Material Vernaculars series will not only serve as a robust publishing venue for work on either end of this continuum but that it will successfully cultivate work that brings them together, expanding the space of overlap in a Venn diagram that I have tried to draw here in words. It is my aspiration that the spirit of the old and the new, and their integration, is captured in the cover image selected for this volume. That photograph, of a basket seller encountered in a small city in a rural district of Guizhou province in Southwest China, brings together handmade bamboo baskets intended for use in everyday labor (a classic old topic) with the ubiquitous multifunction mobile phone (a classic new topic). Some of the baskets shown were reroutedthrough my collectinginto the holdings of the Mathers Museum of World Cultures (setting up their study as a classic old topic), but this encounter took place in the context of a large, multinational, multi-museum project aimed at grappling with the new roles played by museums in local, regional, national, and international heritage regimes (a classic new topic).