Come with me to the University of Essex; round the endless ring road encircling Colchester (Britains oldest town). Turn a sharp right along the lane into the green fields of the campus, past the sign that says access only beyond this point, and into the kind of underground parking area that seems specifically designed to host a dourly climactic shoot-out in The Sweeney although the speed bumps are set just too high for a Ford Granada to get over in safety.

The university building is celebrated for being made from six different kinds of concrete, each of which seems to be engaged in a race to prove it can decay the fastest. Slowly keep on going up the gentle incline into the very furthest reaches of this unabashedly municipal space, and park in the final loading bay on the left. Here the obliging caretaker will kindly let you into the crisply temperature-controlled environment of the Albert Sloman Library Special Collections rooms.

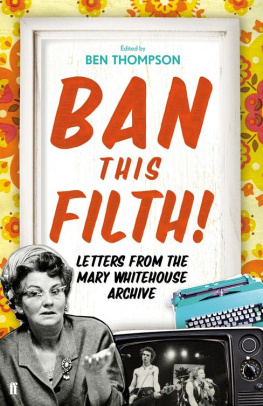

As you turn the lights on and walk through the closely packed book-stacks full of unread volumes of German sociology and back copies of the West Mercia Gazette, the atmosphere is three parts Wernham Hogg (The Offices fictional antiseptic workspace ) to two parts Borgesian labyrinth. When you reach the final compartment at the far end, known as The Cage, theres an incongruous heavy-duty metal door to be opened. Beyond its thick steel grille lies the collection of three hundred large box files which constitute the Mary Whitehouse archive.

Preserved in this sarcophagus of respectable fears are nearly all of the thousands of letters this redoubtable campaigner sent, and most of the many thousands more she subsequently received (some of impassioned support, but others of vehement opposition). The records of Whitehouses National Viewers and Listeners Association include endless newspaper clippings, handbills, mail-outs, legal documents, monitoring forms, draft speeches and completed book manuscripts, all tied up in carefully knotted pink ribbons.

Every now and then, as you open up these Pandoras box files, an artefact of a rather less respectable nature will fall out; perhaps a set of saucy miniature playing cards, or a seven-inch vinyl copy of Alice Coopers Schools Out. There are also an inexplicably large number of photostatted printouts of the lyrics to the Anti-Nowhere Leagues So What, and a hardcore porn handbill that was once posted through the letter box of an eighty-six-year-old woman.

Bridging the gap between these two warring sides filth and anti-filth are the poignant physical traces of the domestic environment Marys letters were written in. One half-finished missive is scrawled on the back of a receipt for the anti-anxiety medication Declinax, another decorates an oatmeal pancake recipe from a fellow churchgoer who had recently recovered from cancer. Then theres the yellowing invitation long ago pressed into service in defence of the nations morals to a Barbecue Cheese and Wine Party: Swimming, dancing, sideshows bar licence applied for, proceeds to Claverly Village Hall rebuilding fund.

Did they barbecue the cheese and the wine, I wonder? Theres no way of knowing, but hopefully this book will be the next-best thing to actually going to that party. And whether the Britain that swims into bleary focus through the Mary Whitehouse archives evangelical Hipstamatic App looks more or less appealing than the one we currently inhabit will be very much in the eye of the beholder.

Ben Thompson, September 2012

Women of Britain manifesto frontispiece

Anyone who grew up in the UK in the 1960s, 70s or 80s will have clear childhood memories of Mary Whitehouse. At once reassuring and slightly scary, she was both the butt of endless jokes and someone adults had good cause to take seriously: a stringent moralising voice in an age when those whose traditional function had been to deliver such improving messages from politicians to churchmen seemed reluctant to take on that role.

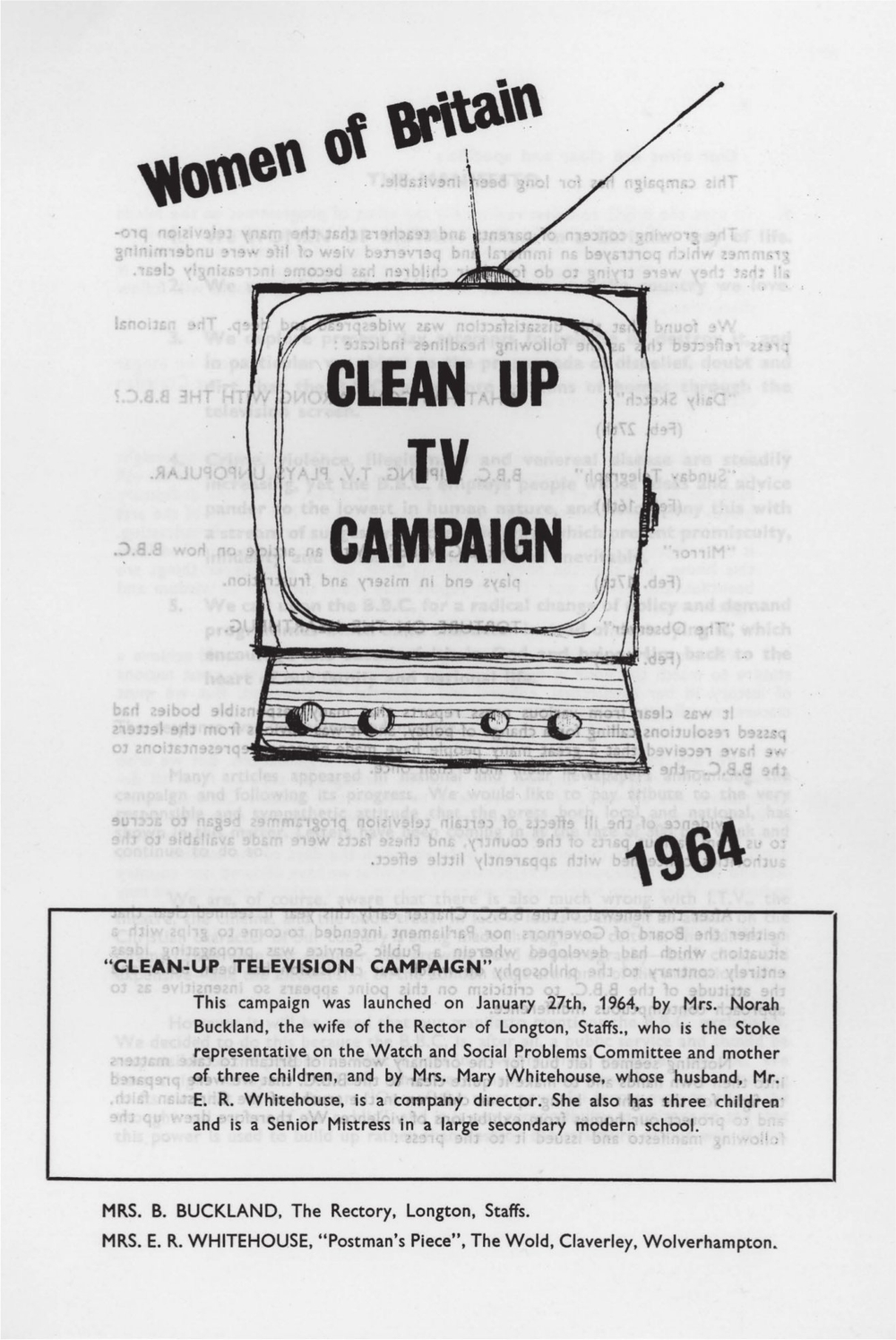

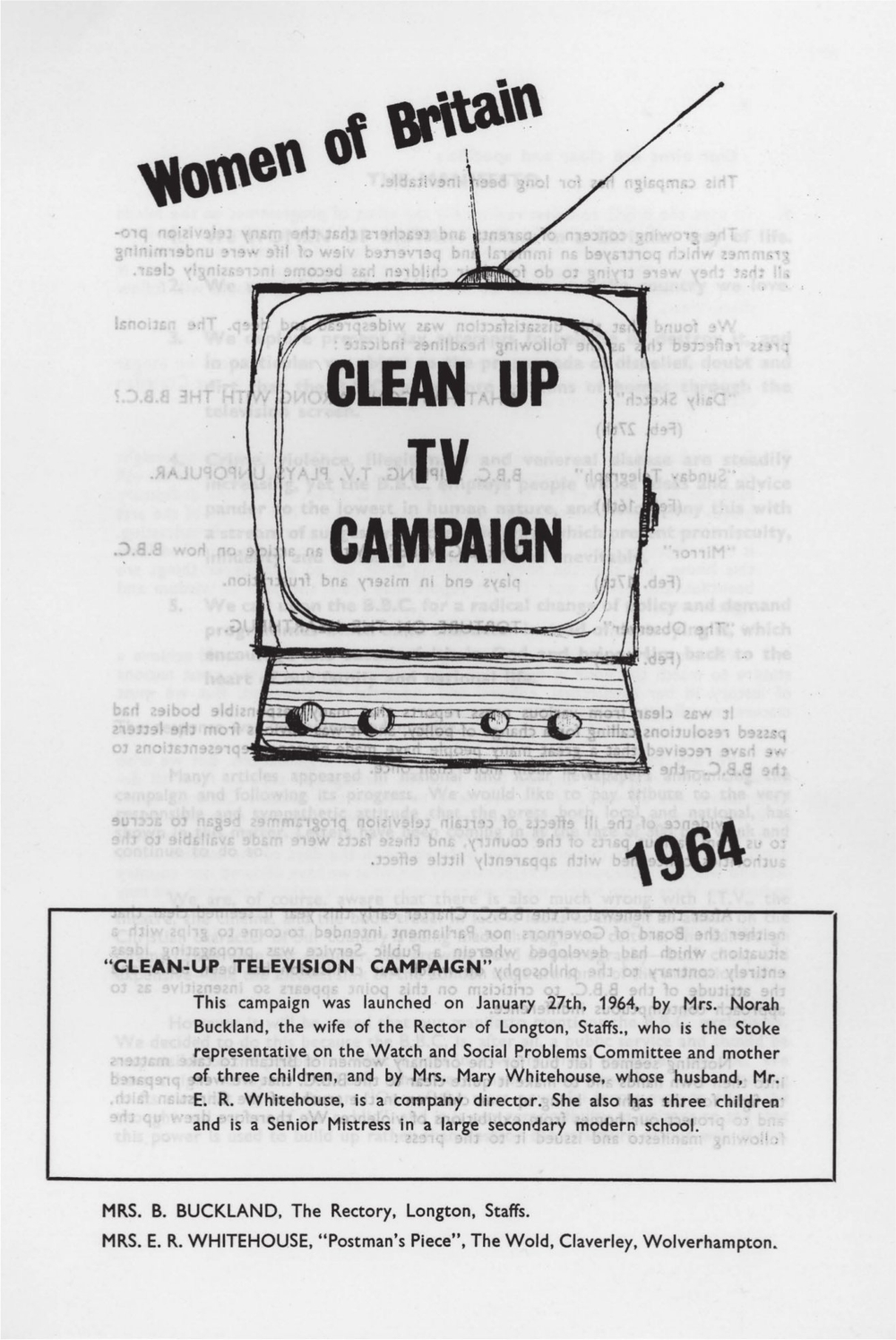

The launch of the Clean Up TV Campaign which she co-founded in early 1964 made this devoutly Christian Shropshire schoolteacher a media star overnight. Over the next three and a half decades, her name became a byword for affronted decency. A one-woman anti-permissiveness SWAT team, she was lampooned by comedians and rock stars, yet feared by liberal churchmen, playwrights, politicians and TV programme-makers alike.

The following crisp early-seventies exchange perfectly encapsulates one aspect of Mary Whitehouses reputation.

Letter to Lord Hill of Luton, then chairman of the BBC

16 June, 1972

Dear Lord Hill,

I understand that the new Rolling Stones record, Exile on Main Street is being played on Radio 1.

This record uses four-letter words. Although they are somewhat blurred, there is no question about what they are meant to be.

I feel sure you will understand the concern felt about this matter, for it is surely no function of the BBC to transmit language which, as shown in a recent court case, is still classed as obscene. The very fact that this programme is transmitted primarily for young people would, one would have thought, have demanded more, not less, care about what is transmitted.

We would be grateful if you would look into this matter.

Yours sincerely,

(Mrs) Mary Whitehouse

Reply from Lord Hill

20th June, 1972

Dear Mrs. Whitehouse,

Thank you for your letter of June 16th in which you state that the tracks from the Rolling Stones record Exile on Main Street, played on Radio I use four-letter words.

I have this morning listened with great care to the tracks we have played on Radio I. I have listened to them at a fast rate, at a medium rate, at a slow rate. Though my hearing is excellent, I did not hear any offending four-letter words whatever.

Could it be that, believing offending words to be there and zealous to discover them, you imagined that you heard what you did not hear?

Yours sincerely

Ally Luton

Mary Whitehouses most readily mockable incarnation was as an indefatigable seeker after offence where none need have been taken a tendency with which this valiant attempt to discern non-existent four-letter outrages would seem to fall neatly into line (excepting the diplomatic veil Lord Hill draws over the song title Turd on the Run). And yet as anyone who has read any of the various forensic retrospective accounts of the abyss of drug-fuelled degradation from which the album in question is now known to have crawled will be obliged to admit in this case the superficial absurdity of the critique did not preclude the possibility that her hypersensitive moral smoke alarm had detected a real fire.

Nor does the Exile on Main St. episode turn out to be an isolated incidence of Mary Whitehouse missing the trees but seeing the wood. Sifting through the vast compendium of outrage that is her correspondence from her exquisitely testy entanglements with successive generations of BBC top brass, to the often less eloquent but sometimes even more heartfelt expressions of shock and horror penned by her sofa-bound army of TV and radio vigilantes a startling new perspective on Whitehouses public life soon begins to reveal itself.

As divisive a figure as Mary Whitehouse undoubtedly was, in one respect the campaigning career of this famously prim and proper polemical powerhouse has been the subject of a rare degree of consensus. Friend and foe alike have generally agreed that her ultimate objective was to shore up the belief systems of the past in the face of a threatening and uncertain future.