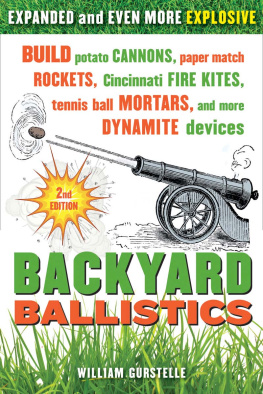

Also by William Gurstelle

Adventures from the Technology Underground

Backyard Ballistics

The Art of the Catapult

Building Bots

To Karen, my helper, consultant, and inspiration.

She makes my heart go whoosh and boom.

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

The instructions and information herein are provided for your use without any guarantee of safety. Each project has been extensively tested in a variety of conditions. But variations, mistakes, and unforeseen circumstances can and do occur. Therefore all projects and experiments are performed at your own risk! If you dont agree with this caveat, then put this book down; it is not for you.

There is no substitute for your own common sense. If something doesnt seem right, stop and review whats going on. You must take responsibility for your personal safety and the safety of others around you.

The author and the publisher expressly disclaim any liability, loss, or risk, personal or otherwise, which is incurred as a consequence, directly or indirectly, of the use and application of any of the contents of this book.

Introduction

S ince my first book, Backyard Ballistics, was published, a couple of things have happened. First, the number of books in my library devoted to researching things that go whoosh, boom, and splat has grown enormously. Concomitantly, the bookshelf holding biographies of inventors has also grown quickly.

Many of the scientists and practical philosophers associated with this field of study are pretty well known. For example, books about Alfred Nobel (the inventor of dynamite), Robert Goddard (the father of liquid fuel rocketry), and Archimedes (the greatest of the ancient Greek scientists and discoverer of the principle of buoyancy) are easy to find. But many more scientific innovators are not as well known as they should be. In this book you will meet several scientists and historical figures who perhaps should be more famous, considering how adept they were at making things go boom and how the events that followed their work changed the course of history.

The names Urban of Hungary, Federico Gianibelli, and Waldo Semon are just about forgotten, and more important, world-changing scientists like Alexander von Humboldt and Count Rumford are familiar to only a few. These men were able experimenters and terrific scientists who shaped wood, cut metal, mixed chemicals, and occasionally got into trouble. But they also did great things.

The other thing thats happened since the publication of Backyard Ballistics is that people often ask me, Are you the fellow who wrote that book about blowing things up?

Well, gollyno, Im not.

I never really think of Backyard Ballistics as being about blowing things up. It is not a cookbook for anarchists, and there are no recipes in it for making bombs. The projects in Backyard Ballistics do result in things going boom, at least occasionally. But is that a good thing? Is there anything inherently good and noble about experimentation and fabrication, when the desired result is nothing more than a really good bang? I myself wasnt sure until I recalled something a friend told me several years ago.

This particular friend, Jim, is a tall, laconic electrical engineer, a product of the northern plains. He grew up in a rural area in northwestern Minnesota, around the towns of Red Lake, Fertile, and Climax. As a boy, he spent his free time taking apart farm machinery and gadgets and then putting them back together. When he was old enough, he joined the air force, hoping to see the world. In the irony of military life, Jim actually wound up seeing more of the northern prairie, since he was assigned to a program targeting instructions for the nuclear missiles that were then hidden underneath North Dakota.

During the 1960s Jim tinkered on the hundreds of Minuteman intercontinental ballistic missiles buried in pop-top tombs under the Dakota winter wheat fields. At the time of his enlistment there were so many rockets up there that if North Dakota had seceded from the Union, it would have become the worlds second-largest nuclear power.

Jims work involved targeting nuclear missiles by straddling the nose cone at the tip of the rocket and shooting the coordinates of visible landmarks through a transitlike device called a theodolite. Then he fed a metal punch tape into the tape-reader fronting the missile guidance system in the communications bay of the rocket. The tape provided the exact coordinates of that weeks top Cold War targetsay, the Soviet Strategic Rocket Force bases at Tatischevo, or the Northern Fleet Command bunker at Severomorsk. This told the sleeping Minuteman exactly where it should head, should the go-code arrive from the Pentagon to wake it up.

From this background of agrarian and military tinkering, Jim took the logical step of enrolling in college after his discharge. Because he enjoys tinkering, he earned his degree in engineering.

The love of tinkering and a concomitant affection for making things go whoosh, or zoom, or even boom, should be the identification badge by which modern engineers are recognized. The greater a persons tinkering skills, Jim told me, the greater the engineer.

In Jims youth, way up there on the rural northern plains, there werent many things to fill the leisure time of teenage boys. Two of the most popular pastimes were drinking and tinkering. While some misspent their youth throwing back beers in ice-fishing shacks on frozen lakes, others tinkered. To certain boys, the long, icy nights and the scarcity of outside stimuli werent privations. They were gifts of time: the cold, clear, and quiet air of the prairie served as a lens to focus their attention. Myriad projects invariably pose themselves to a plains state tinkerer with time on his hands.

Jim observed that those rural and small-town boys (they were mostly boys back then) in the mid-twentieth century who filled their free time with tinkering got good at it. Many who left the farmlands followed the very same path to study engineering as my friend Jim did. They had a practical basis for their knowledge and study, rooted in long hours of advanced tinkering and, occasionally, blowing something upnot violently, not dangerously, but on purpose and with care. They became good, even great engineers.

These engineers looked at themselves not just as technicians or professional designers but as engineer-artists whose creations were both mechanical art and extensions of themselves.

To predict the adult engineering success of a youth, look to his or her propensity for making things go whoosh, boom, or splat. Thomas Edisons childhood chemistry experiments, performed in the baggage car of the train on which he worked, resulted in the accidental destruction of the railroad car. B. F. Skinner, the great social scientist, was proud of the steam cannons and catapults he built as a youngster. Homer Hickam, the NASA engineer who wrote the best-selling book Rocket Boys, predictably enough burned down part of his yard with primitive rocket experiments. A certain Thomas Shelton, of whom well learn more, accidentally demolished his parents kitchen with an experiment gone wrong. And a young engineer named Jack Welch burned down one of his employers factories, yet managed to retain his job. He went on to become the CEO of General Electric.