Editor: LAURA DOZIER

Designer: SARAH GIFFORD

Production Manager: ERIN VANDEVEER

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

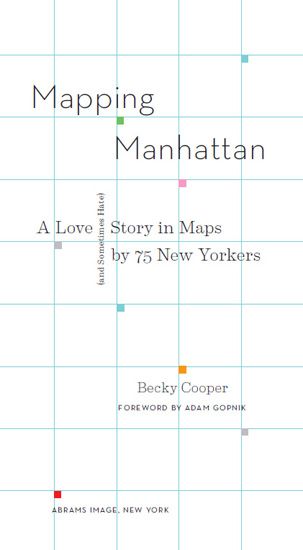

Cooper, Becky.

Mapping Manhattan: a love (and sometimes hate) story in maps by 75 new yorkers/

Becky Cooper.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-4197-0672-1

1. Manhattan (New York, N.Y.)Social life and customsAnecdotes. 2. New York (N.Y.)Social life and customs--Anecdotes. 3. New York (N.Y.)BiographyAnecdotes. 4. Manhattan (New York, N.Y.)Maps. 5. New York (N.Y.)Maps. I. Title.

F128.36.C66 2013

974.71dc23

201203316

Text, maps, and illustrations copyright 2013 Rebecca Cooper

Illustrations by Bonnie Briant

Published in 2013 by Abrams Image, an imprint of ABRAMS. All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher.  Portions of this book originally appeared in different form in the spring 2010 issue of The Harvard Advocate.

Portions of this book originally appeared in different form in the spring 2010 issue of The Harvard Advocate.

Abrams Image books are available at special discounts when purchased in quantity for premiums and promotions as well as fundraising or educational use. Special editions can also be created to specification. For details, contact specialsales@abramsbooks.com or the address below.

115 West 18th Street

New York, NY 10011

www.abramsbooks.com

Contents

Foreword BY ADAM GOPNIK

Maps and memories are bound together, a little as songs and love affairs are. The artifact envelops the emotion, and then the emotion stores away in the artifact: We hear All the Things You Are or Hey There Delilah just by chance while were in love, and then the love is forever after stored in the song. (Someone mentioned this once to Marcel Proust, and he said there might be an idea for a book in it.) So with maps: We go to live somewhere, and then we see a schematic representation of it, and superimposing our memories upon it, we find that it becomes peculiarly alive.  This attachment requires no particular creative energy. It just happens. Even a map of the most ordinary found kindthat map of Schenectady you needed when you went on a bus tripbecomes filled with a particular times particular pleasure. And (this is the truly weird thing) the more limited the map, the bigger the feelings it evokes. I cant see the mtro map of Paris, or hear the roster of its stopsChteau Rouge, Gare de lEst, Chteau dEauwithout feeling myself in Paris on a summer Sunday on the way to the flea market. The map is a stronger version of the trip than a video might be; it is almost a stronger version of the trip than the trip is. Whats more, I look at the subway map of New York, see the dull line of New York numbers33, 42, 51, 59and they fill up at once with memory. Maps, especially schematic ones, are the places where memories go not to die, or be pinned, but to live forever.

This attachment requires no particular creative energy. It just happens. Even a map of the most ordinary found kindthat map of Schenectady you needed when you went on a bus tripbecomes filled with a particular times particular pleasure. And (this is the truly weird thing) the more limited the map, the bigger the feelings it evokes. I cant see the mtro map of Paris, or hear the roster of its stopsChteau Rouge, Gare de lEst, Chteau dEauwithout feeling myself in Paris on a summer Sunday on the way to the flea market. The map is a stronger version of the trip than a video might be; it is almost a stronger version of the trip than the trip is. Whats more, I look at the subway map of New York, see the dull line of New York numbers33, 42, 51, 59and they fill up at once with memory. Maps, especially schematic ones, are the places where memories go not to die, or be pinned, but to live forever.

Whats true even of the utilitarian map is still more true of the purpose-made poetic map. Of all artists, Saul Steinberg is the greatest and wittiest poet of the relation between the made map and memories. The most famous of his maps, of course, is of the relation between the New Yorkers mind and the map he makes of the world, with Tenth and Eleventh Avenues looming vast in the foreground and then the rest of America a vaguely sketched-in space, half the size of Manhattan. But this is only one of a hundred equally beautiful maps Steinberg made of his New York, all turning on his own home, on East 75th Street, as the citys natural center. His essential conviction was that we can only live within mapsand that every good map is oriented around our own hearth.  Its no accident that Steinberg never drew a landscape, except as nostalgic parody or kitsch pastiche, because the landscape is the antithesis of the map. The usual way of writing the history of images is to insist that the map comes first and the landscape is the escape from it: We start with stylized, conceptual depictions of our worldthe ocean chart for the Phoenician sailor showing the way home, the quick charcoal sketch of the bisons location drawn on the side of the caveand slowly begin to see, and then show, the elements that maps cant capture, the irreducible optical presence of the world as it really is; this leaf, this shadow, this morning, this one animal.

Its no accident that Steinberg never drew a landscape, except as nostalgic parody or kitsch pastiche, because the landscape is the antithesis of the map. The usual way of writing the history of images is to insist that the map comes first and the landscape is the escape from it: We start with stylized, conceptual depictions of our worldthe ocean chart for the Phoenician sailor showing the way home, the quick charcoal sketch of the bisons location drawn on the side of the caveand slowly begin to see, and then show, the elements that maps cant capture, the irreducible optical presence of the world as it really is; this leaf, this shadow, this morning, this one animal.  But there is another way of thinking about this: The landscape may be the artificial, warped, artistic visionearned by hard mental work on the part of creator and beholder bothwhile the map is the real thing, the way we see, the way we store, and the way we keep it safe for good. Unroll the canvases lined up, without their stretchers, from the artistic attic of our minds, and what we find are not pictures but depictions, not snapshots but, if you like, map-shots, graphic studies of the relationships forged in memory that let us go on, and move on. This is not a conceit, or not merely one, nor even a metaphor. Cognitive science now insists that our minds make maps before they take snapshots, storing in schematic form the information we need to navigate and make sense of the world. Maps are our first mental language, not our latest. The photographic sketch, with its optical hesitations, is a thing we force from history; the map, with its neat certainties and foggy edges, looks like the way we think.

But there is another way of thinking about this: The landscape may be the artificial, warped, artistic visionearned by hard mental work on the part of creator and beholder bothwhile the map is the real thing, the way we see, the way we store, and the way we keep it safe for good. Unroll the canvases lined up, without their stretchers, from the artistic attic of our minds, and what we find are not pictures but depictions, not snapshots but, if you like, map-shots, graphic studies of the relationships forged in memory that let us go on, and move on. This is not a conceit, or not merely one, nor even a metaphor. Cognitive science now insists that our minds make maps before they take snapshots, storing in schematic form the information we need to navigate and make sense of the world. Maps are our first mental language, not our latest. The photographic sketch, with its optical hesitations, is a thing we force from history; the map, with its neat certainties and foggy edges, looks like the way we think.

Between the found descriptive map we share and the poetic map of the artist lie the smaller improvised personal maps that fill this bookthe maps we cant help but make in our heads, even if we dont always draw them with our hands.  Manhattan is a particularly fit, rich subject for the mental map. Though big in area, it is small, compressed in articulation. More than almost any other city, it was made on purpose. London is a collection of villages drawing ever more tightly together over timeShoreditch, where Shakespeare lived, and Southwark, where he worked, about two miles away, were once felt to be as far apart as Montauk and Westhampton, which have some forty miles separating them; Paris, despite the broad boulevards that cut across it, is still an organic web of small streets that seem to supply an overcharge of memory in themselves.

Manhattan is a particularly fit, rich subject for the mental map. Though big in area, it is small, compressed in articulation. More than almost any other city, it was made on purpose. London is a collection of villages drawing ever more tightly together over timeShoreditch, where Shakespeare lived, and Southwark, where he worked, about two miles away, were once felt to be as far apart as Montauk and Westhampton, which have some forty miles separating them; Paris, despite the broad boulevards that cut across it, is still an organic web of small streets that seem to supply an overcharge of memory in themselves.  New York offers instead a rectilinear grid of numbers and minimal descriptors, a cookie cutter laid down upon a green island. Its most emotive locales are laconically named: Say, Central Park West and 72nd Street. Manhattan is so like the abstract, modernist grid on which Cubist painters were expected to hang their emotions, or objects, in fact, that it isnt an accident that great Cubist paintings, though made in gray Parisian garrets, always put us (as they put their painters) in mind of New York: Song lyrics and old guitars and breakfast tabletops appear through the rigid conceptual scheme of straight verticals and horizontals. And no accident, either, that the New York paintings of Cubist-minded Piet Mondrian, after his immigration here in the 1940s, are among the best mental maps we have of the city, with their perfect evocation of the collision of a high modern sensibility, their taste for geometric abstraction, and a just-off-the-boat arrivals excitement at the blinking, boogie-woogie energy of New York.

New York offers instead a rectilinear grid of numbers and minimal descriptors, a cookie cutter laid down upon a green island. Its most emotive locales are laconically named: Say, Central Park West and 72nd Street. Manhattan is so like the abstract, modernist grid on which Cubist painters were expected to hang their emotions, or objects, in fact, that it isnt an accident that great Cubist paintings, though made in gray Parisian garrets, always put us (as they put their painters) in mind of New York: Song lyrics and old guitars and breakfast tabletops appear through the rigid conceptual scheme of straight verticals and horizontals. And no accident, either, that the New York paintings of Cubist-minded Piet Mondrian, after his immigration here in the 1940s, are among the best mental maps we have of the city, with their perfect evocation of the collision of a high modern sensibility, their taste for geometric abstraction, and a just-off-the-boat arrivals excitement at the blinking, boogie-woogie energy of New York.

Next page

Foreword BY ADAM GOPNIK

Foreword BY ADAM GOPNIK Its no accident that Steinberg never drew a landscape, except as nostalgic parody or kitsch pastiche, because the landscape is the antithesis of the map. The usual way of writing the history of images is to insist that the map comes first and the landscape is the escape from it: We start with stylized, conceptual depictions of our worldthe ocean chart for the Phoenician sailor showing the way home, the quick charcoal sketch of the bisons location drawn on the side of the caveand slowly begin to see, and then show, the elements that maps cant capture, the irreducible optical presence of the world as it really is; this leaf, this shadow, this morning, this one animal.

Its no accident that Steinberg never drew a landscape, except as nostalgic parody or kitsch pastiche, because the landscape is the antithesis of the map. The usual way of writing the history of images is to insist that the map comes first and the landscape is the escape from it: We start with stylized, conceptual depictions of our worldthe ocean chart for the Phoenician sailor showing the way home, the quick charcoal sketch of the bisons location drawn on the side of the caveand slowly begin to see, and then show, the elements that maps cant capture, the irreducible optical presence of the world as it really is; this leaf, this shadow, this morning, this one animal.  But there is another way of thinking about this: The landscape may be the artificial, warped, artistic visionearned by hard mental work on the part of creator and beholder bothwhile the map is the real thing, the way we see, the way we store, and the way we keep it safe for good. Unroll the canvases lined up, without their stretchers, from the artistic attic of our minds, and what we find are not pictures but depictions, not snapshots but, if you like, map-shots, graphic studies of the relationships forged in memory that let us go on, and move on. This is not a conceit, or not merely one, nor even a metaphor. Cognitive science now insists that our minds make maps before they take snapshots, storing in schematic form the information we need to navigate and make sense of the world. Maps are our first mental language, not our latest. The photographic sketch, with its optical hesitations, is a thing we force from history; the map, with its neat certainties and foggy edges, looks like the way we think.

But there is another way of thinking about this: The landscape may be the artificial, warped, artistic visionearned by hard mental work on the part of creator and beholder bothwhile the map is the real thing, the way we see, the way we store, and the way we keep it safe for good. Unroll the canvases lined up, without their stretchers, from the artistic attic of our minds, and what we find are not pictures but depictions, not snapshots but, if you like, map-shots, graphic studies of the relationships forged in memory that let us go on, and move on. This is not a conceit, or not merely one, nor even a metaphor. Cognitive science now insists that our minds make maps before they take snapshots, storing in schematic form the information we need to navigate and make sense of the world. Maps are our first mental language, not our latest. The photographic sketch, with its optical hesitations, is a thing we force from history; the map, with its neat certainties and foggy edges, looks like the way we think. Manhattan is a particularly fit, rich subject for the mental map. Though big in area, it is small, compressed in articulation. More than almost any other city, it was made on purpose. London is a collection of villages drawing ever more tightly together over timeShoreditch, where Shakespeare lived, and Southwark, where he worked, about two miles away, were once felt to be as far apart as Montauk and Westhampton, which have some forty miles separating them; Paris, despite the broad boulevards that cut across it, is still an organic web of small streets that seem to supply an overcharge of memory in themselves.

Manhattan is a particularly fit, rich subject for the mental map. Though big in area, it is small, compressed in articulation. More than almost any other city, it was made on purpose. London is a collection of villages drawing ever more tightly together over timeShoreditch, where Shakespeare lived, and Southwark, where he worked, about two miles away, were once felt to be as far apart as Montauk and Westhampton, which have some forty miles separating them; Paris, despite the broad boulevards that cut across it, is still an organic web of small streets that seem to supply an overcharge of memory in themselves.