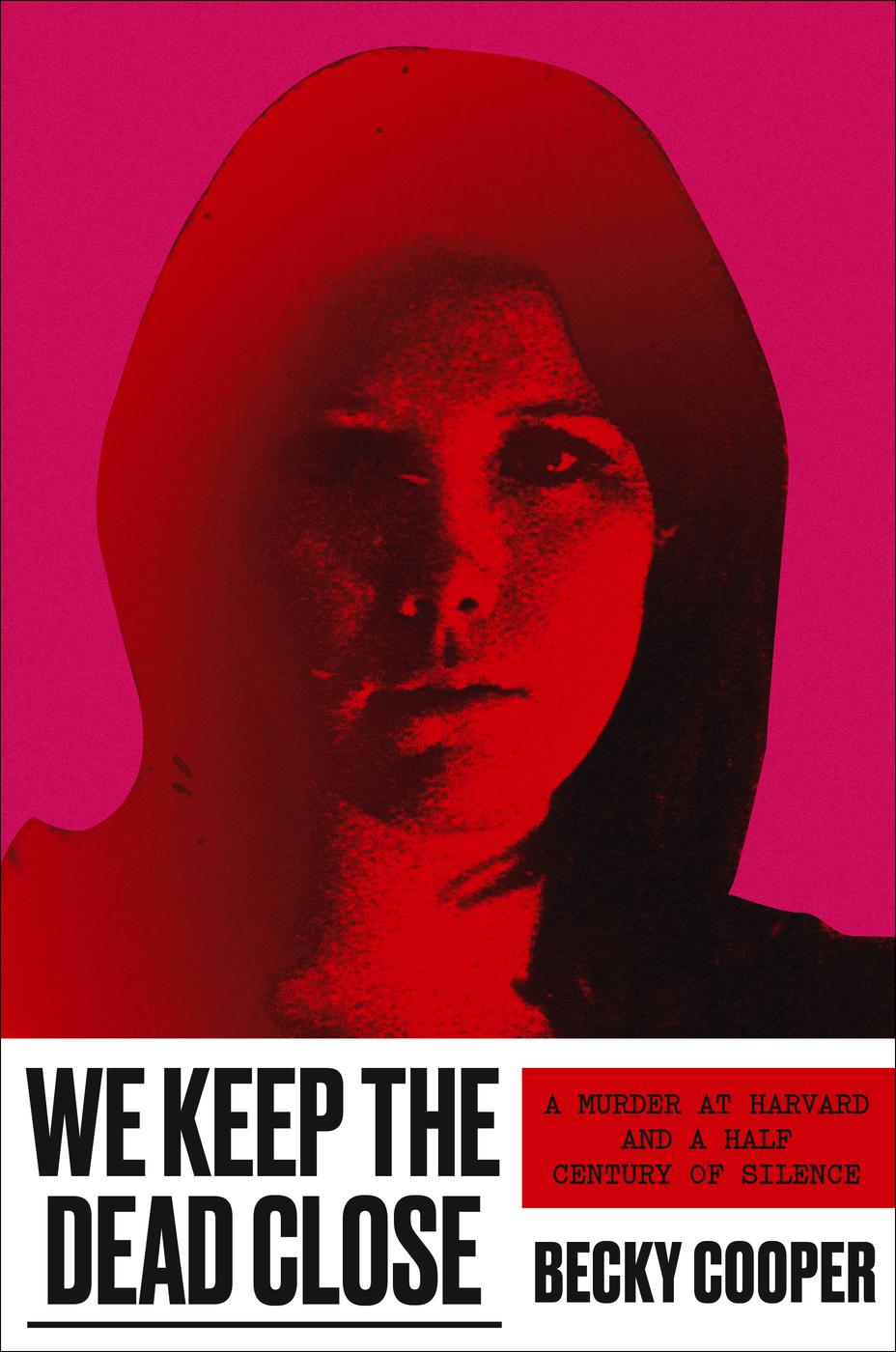

Copyright 2020 by Becky Cooper

Cover design by Alex Merto. Cover photo by Don Mitchell. Cover copyright 2020 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Grand Central Publishing

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

grandcentralpublishing.com

twitter.com/grandcentralpub

First Edition: November 2020

Grand Central Publishing is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Grand Central Publishing name and logo is a trademark of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data has been applied for.

ISBNs: 978-1-5387-4683-7 (hardcover), 978-1-5387-4684-4 (ebook)

E3-20200908-DA-PC-ORI

For my parents

Explore book giveaways, sneak peeks, deals, and more.

Tap here to learn more.

For we live in several worlds, each truer than the one it encloses, and itself false in relation to the one which encompasses it. [] Truth lies in a progressive dilating of the meaning [] up to the point at which it explodes.

Claude Lvi-Strauss, Tristes Tropiques

The primary characteristic of the deepest reaches of the past, especially for the sort of observer whose paramount concerns are those of the present, is the accommodating silence found there. The quieter an epoch on its own terms, the more loudly it can be made to speak, in the way of a ventriloquists dummy, for ours.

Gideon Lewis-Kraus, Is Ancient DNA Research Revealing New Truths

or Falling into Old Traps,

New York Times Magazine

IT WAS THE WARMEST IT had been in more than a week, but Bostonians turning on their morning radio broadcast woke up to gale warnings along the coast. In Cambridge, across the Charles River, the day was equally grim. A wintry mix of fog and rain and snow hung over the city, and the streets of Harvard Square were quiet.

A delivery person piled stacks of that days Harvard Crimson inside the undergraduate houses. The front page was a black-and-white picture of a girl curled up in fetal position on the floor of one of the campus libraries. Her head was propped on a book. Her feet were bare. She had on jeans and a sweater and looked more like a body than a person. The caption read, There was the girl who fell asleep on her book and dreamed, and there was the boy who dreamed of the girl asleep on her book, andDont let the times get you down.

January 7, 1969, was the second day of reading period. For most students, with eleven anxious, prolonged days to study before finals, those first mornings were for sleeping. But for a subset of the anthropology doctoral students, that morning was the most nerve-racking one all year.

By 9 a.m., they were packed into a lecture hall at the top of the Peabody Museum. The five-story red-brick building with its grand European-style black doors served as home base for the universitys Anthropology department. Founded in 1866, the museums history as an institution, its docents proudly remind visitors, is the history of American anthropology.

The students were there to take the first of three parts of their general exams. They had been studying for months, and the stakes were high. If they failed, they risked getting moved off the PhD track into a terminal masters, a gloved way of saying kicked out.

The museum sometimes smelled like the mummies casually stored on its fourth floor: spicy and musty, though not altogether revolting. But that winter morning, all the smells had stilled. Now it was just elbows propped on desks, hands moving across blue books, pens filling in short-answer essays. Between the nerves and the number of students, only a few people noticed that one student had failed to show up: Jane Britton.

MY ROOM IS ON THE third floor of a mansion called Apthorp House, a part of Harvards Adams House dorms. Apthorp, shaped like a wedding cake, is jonquil, that distinctly New England shade of daffodils and buttercream. My bedroom is a cross between a bunker and a tree house, and the ceilings are so low I regularly hit my overhead lamp when I throw my hands up excitedly. From the front door, I can see the room I lived in my sophomore year, as well as the fire escape I used to climb when I locked myself out of that room. Its the same rickety ladder a crush surprised me by scaling that fall. The same landing I sat out on and listened to sad Bob Dylan and wished I smoked when things ended a month later. Some days I catch myself forgetting that ten years have gone by.

Apthorp, everyone agrees, is haunted, and were pretty sure the ghost is General Burgoyne, a British officer who was held captive in the house during the Revolutionary War. We have, inexplicably, a life-size cutout of him in the basement. I cant decide whether its a joke or an educational toolAnd here you have the boots that make those clomping soundsbut theres a touch of cruelty in his continued entrapment.

I share Apthorp with the faculty deans of Adams House who are in charge of house lifedances, the housing lottery, the annual Winnie-the-Pooh Christmas readas well as three recent Harvard graduates. The four of us are called Elves, which means we get room and board in exchange for baking cookies for the undergraduates monthly teas. It makes about as much sense to me as it does to you, but its one of those quirks you get used to at Harvard. Like Norm the French translator with a cotton-candy puff of hair who graduated from Harvard in 1951 and never really left Adams House; or Father George, a fixture in the dining hall for reasons I dont quite understand, who seems to have as many degrees in the hard sciences as he has jokes. Of course, you quickly learn you have to say.

Elves are usually students straight out of graduation. So when Lulu, one of the other Elves, heard I was turning thirty this year, she looked at me like a messenger from the other side. Is it true, she started in her super-earnest tone, that when you turn thirty, all your friends leave you because they get married, and your body falls apart? I hugged my knees, bandaged from a fall that afternoon, to my chest. Mhmm, I nodded to Lulu.

Boston, especially Harvard Square, is a transient place, remade every fall when a new wave of people washes through. The heavy brick of the buildings only emphasizes the impermanence of everything here but the institution itself. When I told friends in Brooklyn that I was moving back to Boston, one quipped, Does anyone do that voluntarily?

I hadnt. When the undergraduates ask, I tell them that Im here writing a book about archaeology in the 1960s. Anything in particular, they ask, eager to make some kind of connection. Not really, I say. Oh, cool, they say, meaning,