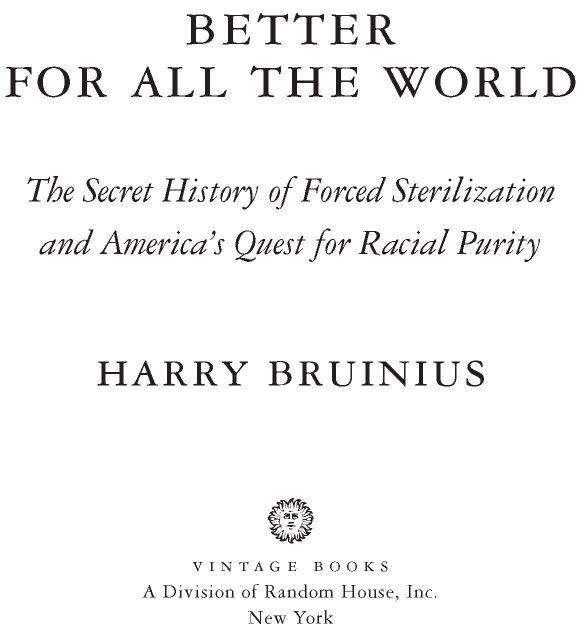

Bruinius deftly combines analysis of how the American quest for moral and social purity prepared people to accept pseudoscience as a basis for national policy with an account of the personal and intellectual development of eugenics most influential American advocates Charles Davenport and Harry Laughlin. The New Yorker

Highly readable.... His story is one worth hearing, and heeding.

Brilliant.... A masterpiece of American cultural history.

Bruinius takes full advantage of his journalistic talents.... Well-written and well-researched. The American Prospect

Eloquent and troubling.... Better for All the World deserves to be closely read. Jerusalem Post

Stephen King, meet your nonfiction counterpart. Some of the scariest things that one can read these days come straight from the history books, including this comprehensive look at the eugenics/racial purity movement. The Washington Times

In his engaging, often moving story, [Bruinius] brings to life an extensive and colorful cast of characters, especially the men (and the occasional woman) who energetically applied English scientist Francis Galtons vision of a scientifically organized Utopia to American society. Chicago Tribune

Mr. Bruinius reminds us of a historical irony we are generally happy to forget: that in the early twentieth century, sterilization joined Prohibition and suffragism as one of the favorite causes of the progressive movement. The New York Sun

Harry Bruinius was born in Chicago and attended Yale University, where he studied theology, and Columbia University, where he studied journalism. He is a frequent contributor to The Christian Science Monitor , a professor of journalism at Hunter College, and the founder of The Village Quill. He lives in Manhattan.

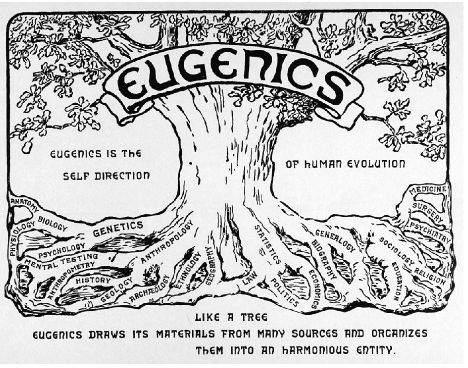

A eugenics leaflet prepared by Harry Laughlin, director of the Eugenics Record Office, ca. 1931.

For My Mother

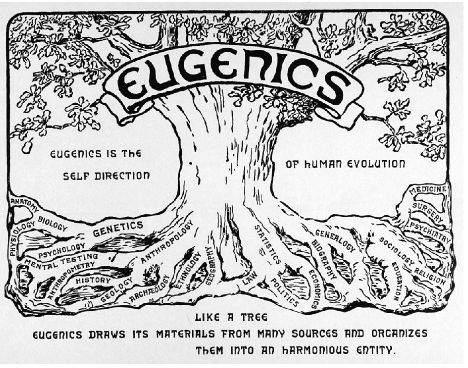

ILLUSTRATIONS

BOOK ONE

INTRODUCTION

The buds unfit to mature, fall; and the weaklings of the flock must perish.

DR. J. H. BELL

I. PROLOGUE

A Simple and Painless Procedure

On a cloudy afternoon on October 19, 1927, as a chilly autumn wind swept down off the Blue Ridge Mountains, rattling the windows of the infirmary at the Virginia Colony for Epileptics and Feeble-minded, Dr. John H. Bell jotted a few notes about an operation he had performed earlier that day. He was the superintendent of this sprawling institution, a campus of regimented brick dormitories and rolling farmland set amid the bluffs overlooking Lynchburg, and one of the countrys finest. The mornings procedure was simple, and dozens of such operations had taken place here over the years. But for this patient he wrote with particular care, since it was a case that might draw a bit of attention.

Patient sterilized this morning under authority of Act of Assembly in 1926, providing for the sterilization of mental defectives, and as ordered by the Board of Directors of this institution, he wrote. She went to the operating room at 9:30 and returned to her bed at 10:30, recovered promptly from the anaesthesia with no untoward after effects anticipated. One inch was removed from each Fallopian tube, the tubes ligated and the ends cauterized by carbolic acid followed by alcohol, and the edges of the broad ligaments brought together with continuous suture. Abdominal wound was united with layer sutures and the approximation of the closure was good. 1

The patient lying before him on the operating table that morning was Carrie Buck, a plump, twenty-one-year-old woman who had been under his care at the Colony for over three years. He knew her well. On the day she was admitted, he had been the first to examine her, and he took special note of her dark eyes and slight features, her low, narrow forehead and high cheekbones. He would see her in the Colonys cafeteria, where she was assigned to work, and his words to her were usually cordial and kind. Yet during most of this time, Dr. Bell and Carrie Buck had been, in name at least, legal adversaries.

So, as he finished his surgical report, he decided to add another formal comment: This is the first case operated on under the sterilization law, and the case was carried through the courts of the State and the United States Supreme Court to test the constitutionality of the Virginia act, and an appeal before the Supreme Court for a rehearing recently having been denied. 2

It was a momentous day. It had taken over three years to test and litigate Carries case, but less than an hour to cut and ligate her Fallopian tubes. But for Dr. Bell, this operation was far more than a legal victory. As a test case, it had been a carefully orchestrated lawsuit meant not only to sterilize Carrie against her will, but also to protect a bold but controversial social policy he believed would improve the welfare of the nation. Today was the beginning. It was cold, but outside the window, beyond the white, two-tiered veranda on the front faade of the infirmary, Dr. Bell could look out over the Colony and consider the long battle he and other reformers had been fighting for decades.

Beyond the veranda, the parallel rows of austere brick dormitories made this state-run institution look something like a military camp, its geometric precision imposing order on a vast Virginia wilderness, even as magnolias and elms gave the Colony the gentle, pastoral feel of a Southern plantation, peaceful and decorous, like Jeffersons Monticello just hours to the north. Dr. Bell, too, had devoted his life, both as a physician and a scientist, to building a more perfect land. Sterilizing Carrie just may have been one of the most important things he had ever done, and as he considered her surgery he may have even dared to think, as a colleague would later tell him, that a hundred years from now you will still have a place in this history of which your descendents may well be proud.3

Yes, our descendants may well be proud. In the end, real progress in this history, in this quest to battle disease and human suffering, will be found in our descendants, Dr. Bell believed. This was why he had to sterilize Carrie, and this was why he was dedicated to the care of epileptics and feebleminded. To those not familiar with the recent discoveries of geneticsa new term in scienceCarrie might have seemed a normal girl, if sassy and simple and even a little slow. But Dr. Bell knew she carried within her, like the taint of original sin, the defective germ-plasm she would pass on to her children. A defect in her genes made her unusually promiscuous, unable to control herself, and prone to bear a child out of wedlock without shame. It kept herand her mother Emma before herfrom being a productive, law-abiding citizen. And he could say with all confidence, too, that Carries illegitimate daughter Vivian, not quite three years old, would follow the same wanton path.