Copyright 2014 by Dayo Olopade

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhco.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN 978-0-547-67831-3

e ISBN 978-0-547-67833-7

v1.0314

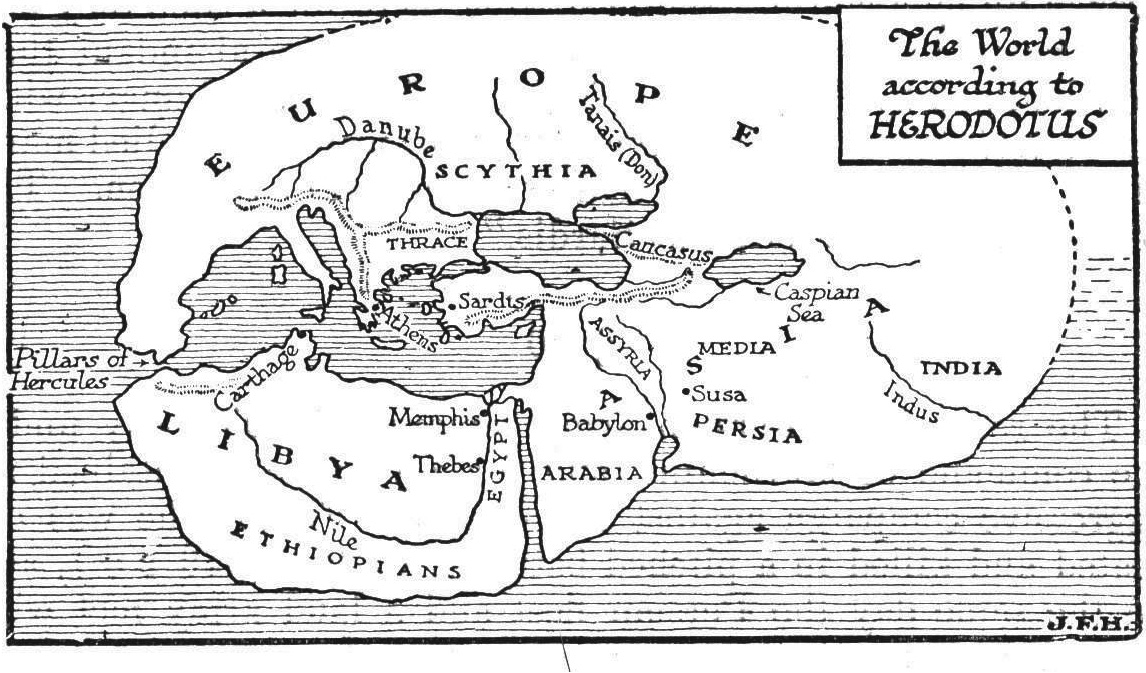

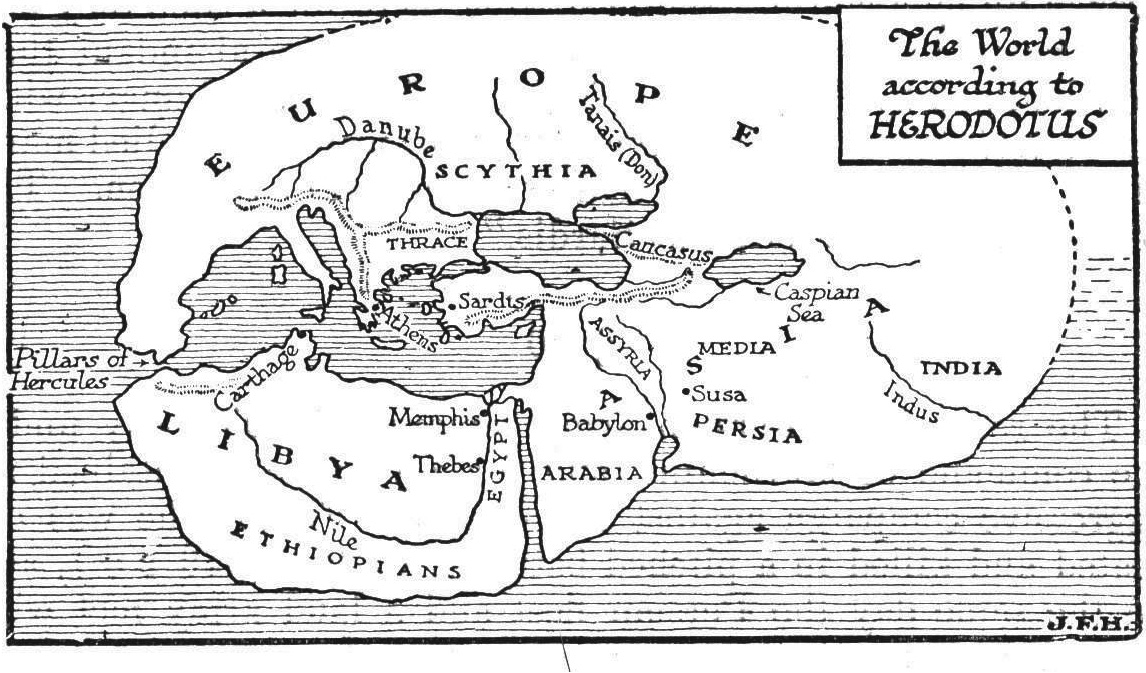

All photographs courtesy of the author, with the following exceptions: Herodotuss map of the world, , openstreetmap.org contributors, available under an Open Database License, with cartography licensed as CC-BY-SA.

This book is for Olufunmilayo Falusi Olopade and

Christopher Olusola Olopade, also known as Mom and Dad.

A man who uses an imaginary map thinking that it is a true one, is likely to be worse off than someone with no map at all.

E. F. Schumacher

Orientation

A New Map of Africa

T HE SEARCH FOR the Nile River took two thousand years too long. The idea of searching is itself crazy: as far as human primates are concerned, the flat pan of water stretching from eastern Uganda to the vast Delta of Egypt has always been there. And yet the first foreign correspondents in Africawhite men from Europewere caught in an amazing race to map the river from tip to tail. Their tales of travel on Africas waterways and into its dense forests sailed back to newspapers in 1850s London, Brussels, and New York. Sending word of new tribes in Ethiopia, or safe passage to the interior lakes of central Africa, these men laid the foundation for a tradition of sensationalist writing about Africa. It was Henry Morton Stanley, in his 1878 account of his travels in the Congo, who coined the term dark continent.

The misunderstanding began before Christ. Herodotuss fifth-century map of Africa left the cradle of civilization looking like an afterthought. (Later, the Mercator Projection sold Africa literally short.) He wrote, I am astonished that men should ever have divided [Africa], Asia and Europe as they have, for they are exceedingly unequal. Europe extends the entire length of the other two, and for breadth will not even (as I think) hear to be compared to them.

In the fifth century BCE, Herodotus created a map of the world as he knew it.For the next millennium, the northward-flowing river puzzled European cartographers. A Greek merchant named Diogenes began a rumor that the source of the Nile lay among the so-called Mountains of the Moon, somewhere in the wilds of Nubia. As trade suffused the continents west coast, existing tribes and landmarks were inked with the exquisite penmanship of eighteenth-century European trade schools. But it was not until 1858 that John Hanning Speke discovered that the longest river in the world begins not on the moon, but at Lake Victoria.

As news of the White Niles source rippled through Europe, Major R. E. Cheesman, the British consul to Ethiopia, remarked, It seemed almost unbelievable that such a famous river... could have been so long neglected. Like Herodotus, Cheesman exposed his Western bias. After all, the Nile bridges languages and climates, north and south of the Sahara. It has fed and ferried millions of people since the days of Moses. At the time of Spekes trip, the population living and trading near the source of the Nile numbered almost three million. It might have been easier for the frantic searchers to ask locals where the big river began. A few could have advised them: here.

The search for an omnipresent river was not merely inefficient; it charts the dynamic that has defined modern African history. Despite centuries of contact (based largely on slave trading), ignorance and hubris long governed Western impressions of what was seen as an impenetrable unknownJoseph Conrads heart of darkness.

So it was not without precedent that European powers, led by the Portuguese, French, British, and Germans, decided to carve up the African continent using maps and borders of their own creation. At the Berlin Conference in 1884, they drew boundaries that had never existed on the continent, scrumming for natural resources from tobacco to peanuts to gold (oil would soon follow). Their borderlines preserved the gap between foreign perception and African reality that has been difficult to close ever since.

More than a century later, Google showed up. Since 2007, the American Internet giant has opened offices in Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, Senegal, South Africa, and Uganda and begun translating its most popular American applications to Africa. Maps were a top priority. Googles team of digital cartographers fanned out across the continent, knitting African streets and cities into the fabric of the World Wide Web. The Americans spared no extravagance: a fleet of red Toyota Priuses mounted with cameras circled cities in South Africa to localize Googles Street View projectjust in time for the 2010 World Cup.

Like the ancient geographers in search of the Nile, the modern Google mappers imported a Western notion of orientation. As anyone who has taken directions in Africa can tell you, were running a different kind of software. In a developed country, a charming female robot might read out clear directions to a numbered street address. In Africa, however, heres what you get:

If you are approaching from the Tuskys roundabout, stay on Langata Road till you have passed the entrance on Langata Road that would get you to Carnivore. Take the first right turn off Langata Road after this point. Drive down Langata Road for approximately half a second, and take the left turn right before the petrol station next to Rafikiz. Drive down this road for half a minute. When you see Psys Langata on your right, take that left.

Confused? These are realand typicaldirections for Nairobi, the Kenyan capital where I lived while reporting this book. Of course, Nairobi and many other cities in Africa have roads and districts with formal names, and some buildings with assigned numbers. But even in the most cosmopolitan cities, the address is beside the point.

Locals use businesses, billboards, bus stops, and hair salons as a dynamic, alternative framework for navigation. We rely on time, relative distance, egocentric directions (right or left), and shared knowledge. In Khartoum, the North Sudanese capital, one prominent local landmark is a building where a Chinese restaurant used to be. In the six months until it was repaired, I gave directions to my home based on a particularly cavernous pothole. Frequently, the final direction is just ask someone.

Anthropologists would call Nairobi streets a high-context environment. Such navigation is a holdover from a time when centralized systems were absent (which, as well see, is often still the case). More importantly, a high-context route from point A is no proof that point B doesnt existit just means you need a different map to find it.

The same goes for modern Africa. Whether youre working for an American tech giant struggling to standardize navigation, an entrepreneur from Brazil looking for new business opportunities, a French tourist in search of adventure, a nonprofit trying to improve lives, or a curious global bystander, you probably dont have a very good map of life south of the Sahara.

In fact, it amazes me how little the world thinks of Africa. I mean this in terms of time and of reputation. As a first-generation Nigerian American, I have personal reasons for paying attention; but what we all think of Africa when we do is very revealing. In 2010, the United Nations celebrated the tenth anniversary of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs)eight ambitious targets, from fighting HIV transmission to improving education around the world. To mark the occasion, the UN sponsored a poster design competition. The winning entry juxtaposed power (leaders of the Group of 8) and poverty (young Africans in line at a refugee camp). The work may be clever graphic design, but the tagline is heartbreaking. Dear world leaders: We are still waiting. A panel of UN judges validated the biggest lie in modern history: that poor and passive Africans exist only in the shadow of Western action.

Next page