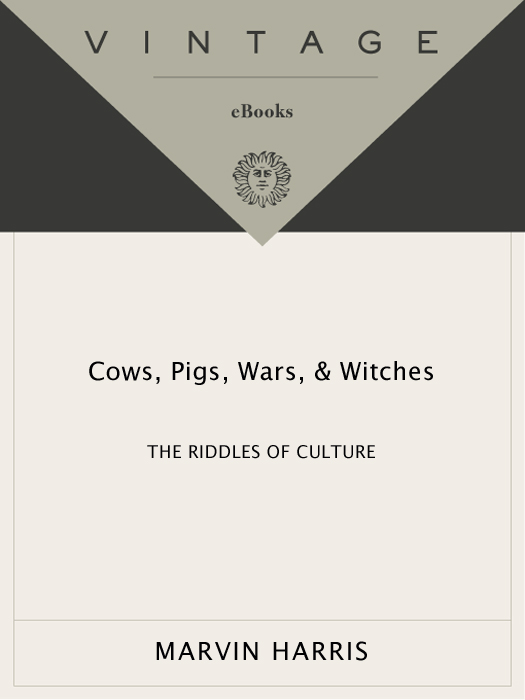

V INTAGE B OOKS E DITION , N OVEMBER 1989

Copyright 1974 by Marvin Harris

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published by Random House, Inc., in 1974.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Harris, Marvin, 1927

Cows, pigs, wars, and witches.

Includes biographical references.

1. EthnologyMiscellanea. 2. Witchcraft.

I. Title.

[GN320.H328 1975] 392 7416455

eISBN: 978-0-307-80122-7

The Song of Victory from The Essene Writings from Qumran by A. Dupont-Sommer, translated by G. Vermes. Translation copyright 1962 by The World Publishing Company. Reprinted by arrangement with The New American Library Inc., New York, N. Y.

v3.1

Preface

I HAD JUST finished trying to convince a class of undergraduates that there was a rational explanation for the Hindu taboo on cow slaughter. I was certain that I had anticipated every conceivable objection. Beaming with confidence, I asked if anyone had any questions. An agitated young man raised his hand. But what about the Jewish taboo on pork?

Some months later I began to do research aimed at explaining why both the Jews and Moslems abhor pork. It took me about a year before I was ready to try out my ideas on a group of colleagues. As soon as I stopped talking, a friend of mine who is an expert on South American Indians said, But what about the Tapirap taboo on venison?

And so it has gone with each of these riddles for which I have tried to find a practical explanation. As soon as I finish explaining one previously inscrutable custom or lifestyle, someone counters with another.

Well, maybe that holds true for potlatch among the Kwakiutl, but how do you explain warfare among the Yanomamo?

I think there may be a shortage of protein there

But what about the cargo cults in the New Hebrides? Explanations of lifestyles are like potato chips. People insist on eating them until the whole bagful is gone.

Thats one of the reasons why this book keeps moving from one subject to another. From India to the Amazon and from Jesus to Carlos Castaneda. But there are some differences as compared with the average bag of potato chips. For one thing, I advise against pulling out the first morsel that strikes your fancy. My explanation for witches depends on the explanation for messiahs and the explanation for messiahs depends on the explanation for big men which depends on the explanation for sexism which depends on the explanation for pig love which depends on the explanation for pig hate which depends on the explanation for cow love. Not that the world began with cow love, but in my own attempt to understand the causes of lifestyles, thats where I began. So please dont grab at random.

Its important that the chapters in this book be seen as building on each other and as having a cumulative effect. Otherwise, I will have no defense against the pummeling that experts in a dozen fields and disciplines will surely want to give me. I respect experts and want to learn from them. But they can be as much of an encumbrance as an asset if you have to depend on several of them at once. Have you ever tried to ask a specialist in Hinduism about pig love in New Guinea, or an authority on New Guinea about pig hate among Jews, or an expert on Judaism about messiahs in New Guinea? (It is in the nature of the beast to crave only one potato chip for its entire life.)

My excuse for venturing across disciplines, continents, and centuries is that the world extends across disciplines, continents, and centuries. Nothing in nature is quite so separate as two mounds of expertise.

I respect the work of individual scholars who patiently expand and perfect their knowledge of a single century, tribe, or personality, but I think that such efforts must be made more responsive to issues of general and comparative scope. The manifest inability of our overspecialized scientific establishment to say anything coherent about the causes of lifestyles does not arise from any intrinsic lawlessness of lifestyle phenomena. Rather, I think it is the result of bestowing premium rewards on specialists who never threaten a fact with a theory. A proportionate relationship such as has existed for some time now between the volume of social research and the depth of social confusion can mean only one thing: the aggregate social function of all that research is to prevent people from understanding the causes of their social life.

The pundits of the knowledge establishment insist that this state of confusion is due to a shortage of studies. Soon there will be a seminar in the sky based on ten thousand new field trips. But we shall know less, not more, if these scholars have their way. Without a strategy aimed at bridging the gap between specialties and at organizing existing knowledge along theoretically coherent lines, additional research will not lead to a better understanding of the causes of lifestyles. If we genuinely seek casual explanations, we must have at least some rough idea about where to look among the potentially inexhaustible facts of nature and culture. I hope that my own work will someday be found to have contributed toward the development of such a strategytoward showing where to look.

Contents

Prologue

T HIS BOOK is about the causes of apparently irrational and inexplicable lifestyles. Some of these enigmatic customs occur among preliterate or primitive peoplesfor example, the boastful American Indian chiefs who burn their possessions to show how rich they are. Others belong to developing societies, my favorite being the Hindus who refuse to eat beef even though theyre starving. Still others have to do with messiahs and witches who are part of the mainstream of our own civilization. To make my point, I have deliberately chosen bizarre and controversial cases that seem like insoluble riddles.

Ours is an age that claims to be the victim of an overdose of intellect. In a vengeful spirit, scholars are busily at work trying to show that science and reason cannot explain variations in human lifestyles. And so it is fashionable to insist that the riddles examined in the chapters to come have no solution. The ground for much of this current thinking about lifestyle enigmas was prepared by Ruth Benedict in her book Patterns of Culture. To explain striking differences among the cultures of the Kwakiutl, the Dobuans, and the Zuni, Benedict fell back upon a myth which she attributed to the Digger Indians. The myth said: God gave to every people a cup, a cup of clay, and from this cup they drank their life They all dipped in the water but their cups were different. What this has meant to many people ever since is that only God knows why the Kwakiutl burn their houses. Ditto for why the Hindus refrain from eating beef, or the Jews and Moslems abhor pork, or why some people believe in messiahs while others believe in witches. The long-term practical effect of this suggestion has been to discourage the search for other kinds of explanations. For one thing is clear: If you dont believe that a puzzle has an answer, youll never find it.

To explain different patterns of culture we have to begin by assuming that human life is not merely random or capricious. Without this assumption, the temptation to give up when confronted with a stubbornly inscrutable custom or institution soon proves irresistible. Over the years I have discovered that lifestyles which others claimed were totally inscrutable actually had definite and readily intelligible causes. The main reason why these causes have been so long overlooked is that everyone is convinced that only God knows the answer.