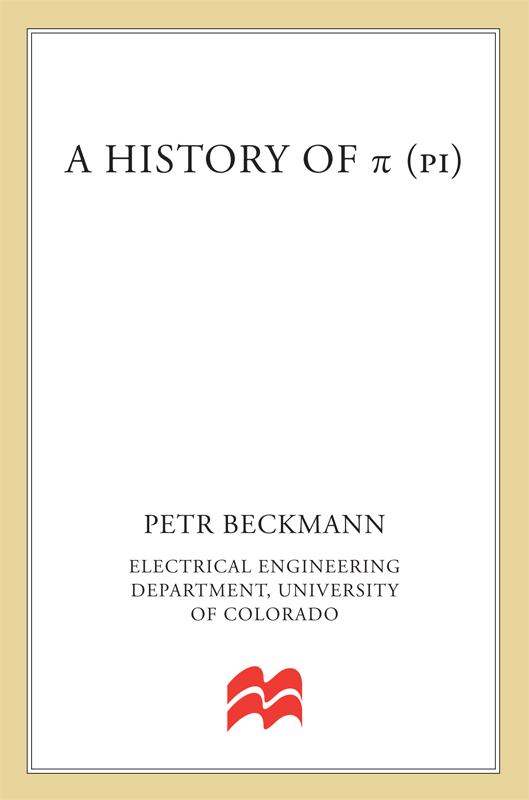

Petr Beckmann - A History of Pi

Here you can read online Petr Beckmann - A History of Pi full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1976, publisher: St. Martins Press, genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:A History of Pi

- Author:

- Publisher:St. Martins Press

- Genre:

- Year:1976

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A History of Pi: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "A History of Pi" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The history of pi, says the author, though a small part of the history of mathematics, is nevertheless a mirror of the history of man. Petr Beckmann holds up this mirror, giving the background of the times when pi made progress -- and also when it did not, because science was being stifled by militarism or religious fanaticism.

A History of Pi — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "A History of Pi" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

TO SMUDLA,

who never doubted the success of this book

The history of is a quaint little mirror of the history of man. It is the story of men like Archimedes of Syracuse, whose method of calculating defied substantial improvement for some 1900 years; and it is also the story of a Cleveland businessman, who published a book in 1931 announcing the grand discovery that was exactly equal to 256/81, a value that the Egyptians had used some 4,000 years ago. It is the story of human achievement at the University of Alexandria in the 3rd century B.C.; and it is also the story of human folly which made mediaeval bishops and crusaders set the torch to scientific libraries because they condemned their contents as works of the devil.

Being neither an historian nor a mathematician, I felt eminently qualified to write that story.

That remark is meant to be sarcastic, but there is a kernel of truth in it. Not being an historian, I am not obliged to wear the mask of dispassionate aloofness. History relates of certain men and institutions that I admire, and others that I detest; and in neither case have I hesitated to give vent to my opinions. However, I believe that facts and opinion are clearly separated in the following, so that the reader should run no risk of being overly influenced by my tastes and prejudices.

Not being a mathematician, I am not obliged to complicate my explanations by excessive mathematical rigor. It is my hope that this little book might stimulate non-mathematical readers to become interested in mathematics, just as it is my hope that students of physics and engineering might become interested in the history of the tools they are using in their work. There are, however, two sure and all too well tried methods of how to make mathematics repugnant: One is to brutalize the reader by assertions without proof; the other is to hit him over the head with epsilonics and proofs of existence and unicity. I have tried to steer a middle course between the two.

A history of containing only the bare facts and dates when who did what to tends to be rather dull, and I thought it more interesting to mix in some of the background of the times in which made progress. Sometimes I have strayed rather far afield, as in the case of the Roman Empire and the Middle Ages; but I thought it just as important to explore the times when did not make any progress, and why it did not make any.

The mathematical level of the book is flexible. The reader who finds the mathematics too difficult in some places is urged to do what the mathematician will do when he finds it too trivial: Skip it.

This book, small as it is, would not have been possible without the wholehearted cooperation of the staff of Golem Press, and I take this opportunity to express my gratitude to every one of them. I am also indebted to the Archives Division of the Indiana State Library for making available photostats of Bill 246, Indiana House of Representatives, 1897, and to the Cambridge University Press, Dover Publications and Litton Industries for granting permission to reproduce copyrighted materials without charge. Their courtesy is acknowledged in the notes accompanying the individual figures.

I much enjoyed writing this book, and it is my sincere hope that the reader will enjoy reading it, too.

Petr Beckmann

Boulder, Colorado

August 1970

PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION

After all but calling Aristotle a dunce, spitting on the Roman Empire, and flipping my nose at some other highly esteemed institutions, I had braced myself for the reviews that would call this book the sick product of an insolent ignoramus. My surprise was therefore all the more pleasant when the reviews were very favorable, and the first edition went out of print in less than a year.

I am most grateful to the many readers who have written in to point out misprints and errors, particularly to those who took me to task (quite rightly) for ignoring the recent history of evaluating by digital computers. I have attempted to remedy this shortcoming by adding a chapter on in the computer age.

Mr. D.S. Candelaber of Golem Press had the bright idea of imprinting the end sheets of the book with the first 10,000 decimal places of , and the American Mathematical Society kindly gave permission to reproduce the first two pages of the computer print-out as published by Shanks and Wrench in 1962. A reprint of this work was very kindly made available by one of the authors, Dr. John W. Wrench, Jr. To all of these, I would like to express my sincere thanks. I am also most grateful to all readers who have given me the benefit of their comments. I am particularly indebted to Mr. Craige Schensted of Ann Arbor, Michigan, and M. Jean Meeus of Erps-Kwerps, Belgium, for their detailed lists of misprints and errors in the first edition.

P.B.

Boulder, Colorado

May 1971

PREFACE TO THE THIRD EDITION

Some more errors have been corrected and the type has been re-set for the third edition.

A Japanese translation of this book was published in 1973.

Meanwhile, a disturbing trend away from science and toward the irrational has set in. The aerospace industry has been all but dismantled. College enrollment in the hard sciences and engineering has significantly dropped. The disoriented and the gullible flock in droves to the various Maharajas of Mumbo Jumbo. Ecology, once a respected scientific discipline, has become the buzzword of frustrated housewives on messianic ego-trips. Technology has wounded affluent intellectuals with the ultimate insult: They cannot understand it any more.

Ignorance, anti-scientific and anti-technology sentiment have always provided the breeding ground for tyrannies in the past. The power of the ancient emperors, the mediaeval Church, the Sun Kings, the State with a capital S, was always rooted in the ignorance of the oppressed. Anti-scientific and anti-technology sentiment is providing a breeding ground for encroaching on the individuals freedoms now. A new tyranny is on the horizon. It masquerades under the meaningless name of Society.

Those who have not learned the lessons of history are destined to relive it.

Must the rest of us relive it, too?

P.B.

Boulder, Colorado

Christmas 1974

History records the names of royal bastards, but cannot tell us the origin of wheat.

JEAN HENRI FABRE

(1823-1915)

A million years or so have passed since the tool-wielding animal called man made its appearance on this planet. During this time it learned to recognize shapes and directions; to grasp the concepts of magnitude and number; to measure; and to realize that there exist relationships between certain magnitudes.

The details of this process are unknown. The first dim flash in the darkness goes back to the stone age the bone of a wolf with incisions to form a tally stick (see figure ). The flashes become brighter and more numerous as time goes on, but not until about 2,000 B.C. do the hard facts start to emerge by direct documentation rather than by circumstantial evidence. And one of these facts is this: By 2,000 B.C., men had grasped the significance of the constant that is today denoted by , and that they had found a rough approximation of its value.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «A History of Pi»

Look at similar books to A History of Pi. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book A History of Pi and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.