Mayen Beckmann

Politics is a subordinate matter; its form of appearance constantly changes depending on the needs of the masses, the same way cocottes adjust to the needs of men by transforming and masking themselves. Because of that it is not fundamental. That is about what endures, what is unique, what is in the stream of illusions what is eliminated from the workings of the shadows, wrote Beckmann to Stephan Lackner on 29 January 1938 when Lackner invited him to take part in an exhibition in Paris which, like the London exhibition in the New Burlington Galleries, aimed to show people outside Germany what the politics of Nazi Germany would no longer tolerate.

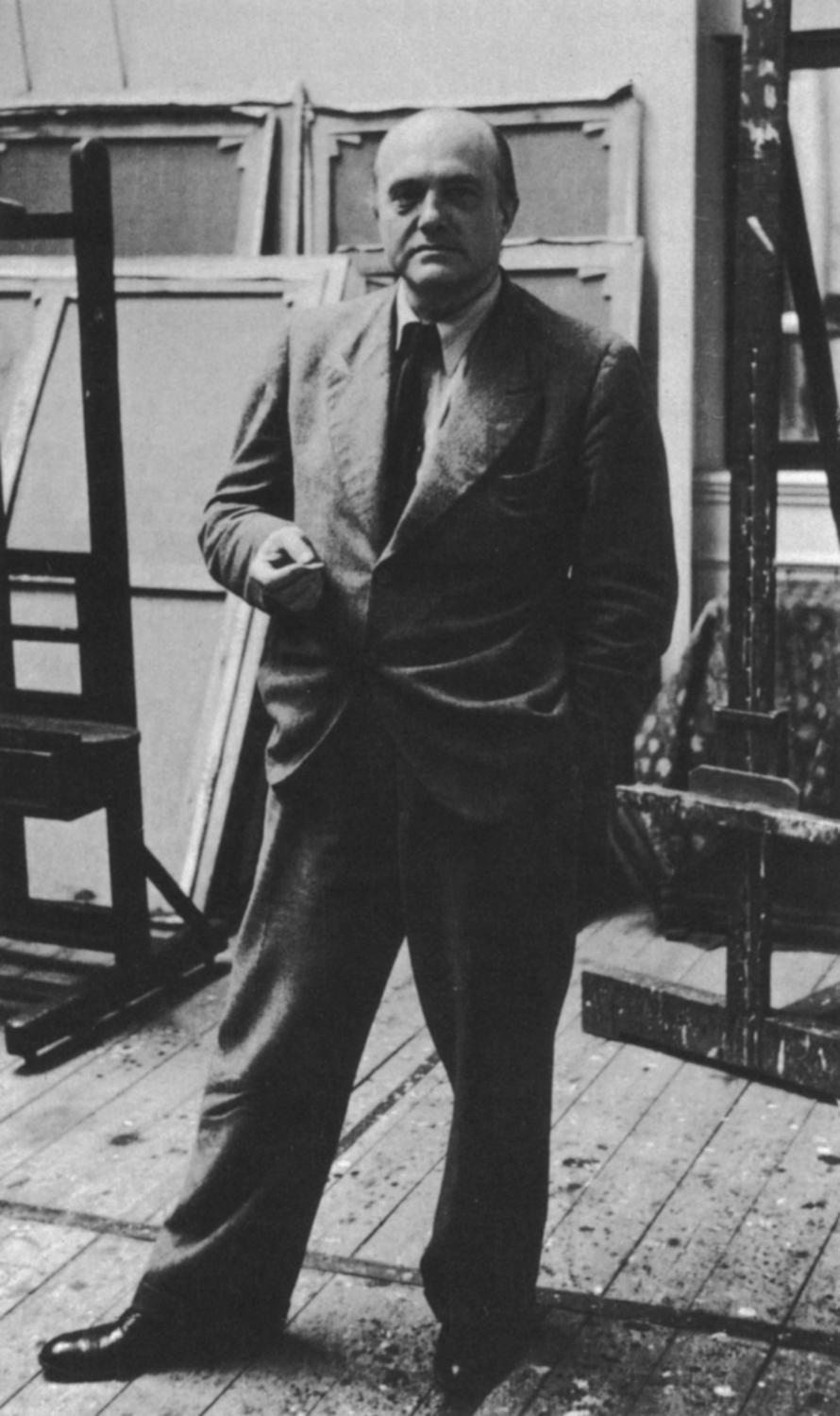

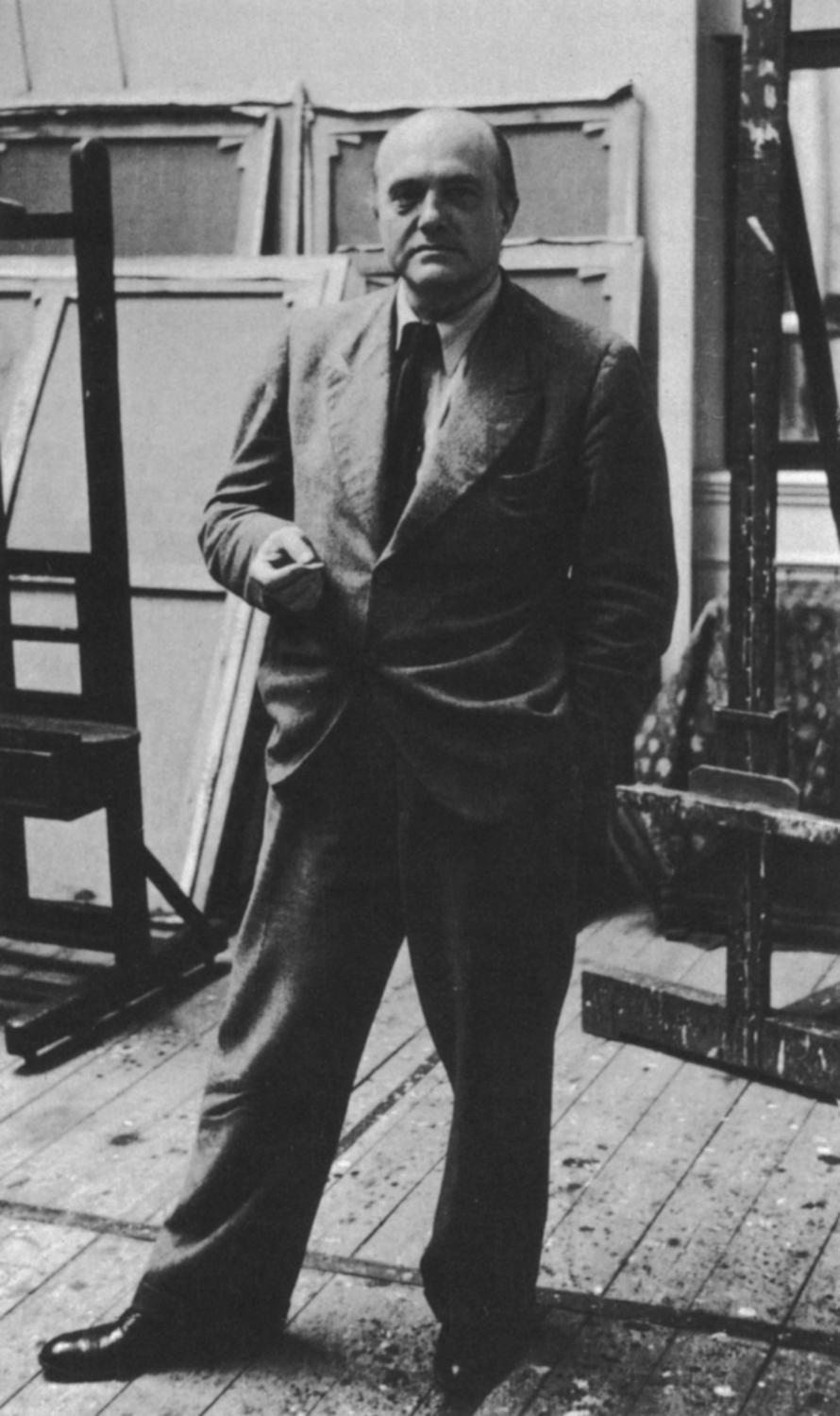

Political change had robbed Beckmann of his sphere of artistic activity in Germany. In 1937, after the Degenerate Art exhibition opened in Munich with a programmatic speech given by Hitler and which toured Germany thereafter, circumstances became so threatening that Beckmann and his wife fled immediately to Holland. In Amsterdam they soon found a tiny flat with a large tobacco storeroom to use as a studio, where the figures of Beckmanns imagination henceforth met and thrust themselves onto canvas or paper.

Without any doubt, Beckmann did not believe that this place of passage would, for the next ten years, become his home and refuge and that all attempts to move on to France or America would be hindered at the last minute by the negative stance of those countries, and would then be thwarted by German troops marching into the Netherlands. For Beckmann, who since the 1920s had always stressed that he was a European rather than a German artist and whose artistic antecedents were the great painters of the European tradition, the unheated tobacco storeroom would for ten years become the sole space of freedom.

The text republished here is one of four programmatic speeches that Beckmann, scarcely able to speak English, gave in England and America: it is the first, and the longest and most fundamental. In the middle of his life he was 54 years old robbed of the network of dealers, museum directors, critics , collectors and friends, and living in a country where he could not speak the language, he was commissioned to examine the sources of his art using the spoken word. He was called upon to say which formal questions occupied him and how he responded to other stylistic innovations of the time such as Cubism, abstract painting or Surrealism.

Intellectual formulation was not his habit, neither as painter nor as an artist who expressed himself in words. So he wrote a speech, with long dashes to give the spoken rhythm, in which he addressed the full spectrum of his professional concerns, from sober description of life events and work processes, painterly technique and the importance of seeing, right through to his artistic vision. A figure comes into being in his speech, created by the artist, who sings a hymn to the images we see in his own pictures. William Blake appears to Beckmann in a dream and promises solace in the recognition of the beauty of creation in the higher spheres of perception.

In this moment Beckmann appears to decide in favour of sleeping and dreaming, like Kundry at the crossroads between good and evil, black and white, history and transcendence in Richard Wagners Parsifal. Put the picture away or, preferably, send it back to me, dear Valentin. If people cannot understand it based on their inner engagement with these matters , then there is no point in showing the thing at all. This comment, from a letter to his dealer Curt Valentin of 11 February 1938, reveals Beckmanns attitude to the language of explanation, only half a year before he wrote the text published in the present volume.

It almost seems that it was only when all established possibilities for expression were lost that Beckmann could attempt to convey in words what he would otherwise have painted.

Berlin, January 2003

Beckmann in his studio in Amsterdam 1938

Max Beckmann Archive, Berlin

Max Beckmann

Before I begin to give you an explanation, an explanation which it is nearly impossible to give, I would like to emphasize that I have never been politically active in any way. I have only tried to realize my conception of the world as intensely as possible.

Painting is a very difficult thing. It absorbs the whole man, body and soul thus I have passed blindly many things which belong to the real and political life.

I assume, though, that there are two worlds: the world of spiritual life and the world of political reality . Both are manifestations of life which may sometimes coincide but are very different in principle. I must leave it to you to decide which is the more important.

What I want to show in my work is the idea which hides itself behind so-called reality. I am seeking for the bridge which leads from the visible to the invisible , like the famous cabalist who once said: If you wish to get hold of the invisible you must penetrate as deeply as possible into the visible.

My aim is always to get hold of the magic of reality and to transfer this reality into painting to make the invisible visible through reality. It may sound paradoxical , but it is, in fact, reality which forms the mystery of our existence.

What helps me most in this task is the penetration of space. Height, width and depth are the three phenomena which I must transfer into one plane to form the abstract surface of the picture, and thus to protect myself from the infinity of space. My figures come and go, suggested by fortune or misfortune. I try to fix them divested of their apparent accidental quality.

One of my problems is to find the Ego, which has only one form and is immortal to find it in animals and men, in the heaven and in the hell which together form the world in which we live.

Space, and space again, is the infinite deity which surrounds us and in which we are ourselves contained.

That is what I try to express through painting, a function different from poetry and music but, for me, predestined necessity.

When spiritual, metaphysical, material or immaterial events come into my life, I can only fix them by way of painting. It is not the subject which matters but the translation of the subject into the abstraction of the surface by means of painting. Therefore I hardly need to abstract things, for each object is unreal enough already, so unreal that I can only make it real by means of painting.

Often, very often, I am alone. My studio in Amsterdam, an enormous old tobacco store-room, is again filled in my imagination with figures from the old days and from the new, like an ocean moved by storm and sun and always present in my thoughts.

Then shapes become beings and seem comprehensible to me in the great void and uncertainty of the space which I call God.

Sometimes I am helped by the constructive rhythm of the Cabala, when my thoughts wander over Oannes Dagon to the last days of drowned continents . Of the same substance are the streets with their men, women and children; great ladies and whores; servant girls and duchesses. I seem to meet them, like doubly significant dreams, in Samothrace and Piccadilly and Wall Street. They are Eros and the longing for oblivion.

All these things come to me in black and white like virtue and crime. Yes, black and white are the two elements which concern me. It is my fortune, or misfortune , that I can see neither all in black nor all in white. One vision alone would be much simpler and clearer, but then it would not exist. It is the dream of many to see only the white and truly beautiful, or the black, ugly and destructive. But I cannot help realizing both, for only in the two, only in black and in white, can I see God as a unity creating again and again a great and eternally changing terrestrial drama .