Abel Ferrara

Contemporary Film Directors

Edited by James Naremore

The Contemporary Film Directors series provides concise, well-written introductions to directors from around the world and from every level of the film industry. Its chief aims are to broaden our awareness of important artists, to give serious critical attention to their work, and to illustrate the variety and vitality of contemporary cinema. Contributors to the series include an array of internationally respected critics and academics. Each volume contains an incisive critical commentary, an informative interview with the director, and a detailed filmography.

A list of books in the series appears

at the end of this book.

Abel Ferrara

Nicole Brenez

Translated from the French by

Adrian Martin

UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS PRESS

URBANA AND CHICAGO

2007 by Nicole Brenez

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

1 2 3 4 5 C P 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Brenez, Nicole.

[Abel Ferrara. English]

Abel Ferrara / Nicole Brenez ; translated from the French by Adrian Martin.

p. cm. (Contemporary film directors)

Filmography: p.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-252-03154-0 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-252-03154-7 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-252-07411-0 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-252-07411-4 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Ferrara, Abel, 1951Criticism and interpretation.

I. Title. II. Series.

PN1998.3.F465B7413 2007

791.4302'33092dc22 [B] 2006011276

Maybe it comes from being brought up in America and idolizing Patrick Henry and all these guys. Its about freedom of speech and will.

Abel Ferrara (2002)

Give me liberty or give me death.

Patrick Henry (1775)

Contents

Acknowledgments

I warmly thank Bernard Benoliel, Emmanuel Bonin, Charles-Antoine Bosson, Stphane Delorme, Philippe Delvosalle, Ivora Cusak, Fergus Daly, Agathe Dreyfus, Pierre Hecker, Alexander Horwath, Kent Jones, Bernd Kiefer, Maria Klonaris, Solange Marcin, Gabriela Trujillo, and Galle Vidalie for their help with this book. Special thanks go to Thanas husband, Robert Lund.

Several parts of this book were encouraged and supported by commissions, some from eminent Ferrarans: Aim Ancian (Sofa), Raymond Bellour (Trafic), Alain Bergala, Carole Desbarats, David Dessites (Dreamlight Entertainment), Catherine Gillet (Muse du Cinma de Bruxelles), Danielle Hibon (Muse du Jeu de Paume), Luc Lagier (Court-Circuit), Jean-Pierre Moussaron (Why Not?), Olivier Pierre (lEcran de Saint-Denis), Muriel Thom (Court-Circuit), Jean-Baptiste Thoret (Simulacres), Genevive Troussier (Caf des Images), Philippe Truffaut (Court-Circuit), and Jean-Pierre Vasseur (Opening).

This book originated in a course I taught at Universit Paris I (Institut dArt et dArchologie), directed by Professor Jean Gili. I fondly thank all my friends and students who attended this course so early on a Saturday morning; for their remarkable contributions, I would like to acknowledge Xavier Baert, Briana Berg de Marignac, Laure Bergala, Laurent Champoussin, Cassandra Cuman, Marc Dante, Sverin de Lajarte, meric de Lastens, Vincent Deville, Jean-Marc Elsholz, Yann Gonzalez, Florent Guzengar, Jrme Momcilovicz, Pascal Snequier, Seung-hee Seo, and Vivien Villani. In this context, Adrian Martin and Brad Stevens camefrom Melbourne and London, respectivelyto offer us magnificent seminars.

Thanks to Lionel Soukaz for his crucial remarks on The Addiction, which more than any other commentary prompted my reflections on this film.

Without the daily support of Michelle Brenez, Pierre-Jacques Brenez, and Titus Brenez-Michaud, I would not have been able to write a single line of this book.

The manuscript benefited from indispensable rereadings by Ferraran experts, whom I can never thank enough: Acha Bahcelioglu, Sbastien Clerget, Stphane du Mesnildot, Sylvain George, Pierre Gras, David Matarasso, Alberto Pezzotta, and Louis-George Schwartz. Special thanks to David Pellecuer for his inexhaustible kindness.

Adrian Martinwith the invaluable help of Helen Bandis and Grant McDonald, his comrades at Rougestrengthened the content of the book by carefully verifying every shot and phenomenon described (as well as finding every citation) for the English translation. Raymond Bellour scrutinized the original manuscript with incomparabale care. I thank them all affectionately for the time they devoted to this project and for the rigor that is directly proportionate to their sensitivity and intellectual generosity.

At the origin of this book, as with so many others, there was an initiative by Jonathan Rosenbaum, without whom international cinephilic life would not be as living, fluent, and fertile as it currently is.

I warmly thank James Naremore, director of the Contemporary Film Directors series at the University of Illinois Press, for his trust and patience.

I dedicate this work to Brad Stevens, a true cinema historian, with affection, gratitude, and admiration.

Abel Ferrara

A Cinema of Negation

Some Ethical Stakes in Ferraras Cinema

To represent is already a murder.

Georges Bataille (1952)

American Boy, European Friends

Abel Ferrara is to cinema what Joe Strummer is to music: a poet who justifies the existence of popular forms. Without them, the genre film or the pop song would be no more than objects of cultural consumption. In this material world run on injustice and terror, where popular is confused with industrial, any cultural expression that does not hurl an angry cry or wail a song of mad love (often one and the same) merely collaborates in the regulation and preservation of this world. Is Ferrara, along with Jim Jarmusch, Tsui Hark, and Kinji Fukasaku, right to (even accidentally) redeem genre cinema? Would it not be preferable for them to desert the dirty terrain of what Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer named the culture industry and, like Jonas Mekas or Stan Brakhage, invent their own territories, forms, and artistic gestures?

Ferraras films offer an answer. How could anyone except a melancholic criminal speak to us in the name of the good (King of New York; 1990)? Who but a paranoid cop could make us believe for a second in the virtues of forgiveness (Bad Lieutenant; 1992)? Who today could bear to listen to a moral lesson if it was not acted out by a drug-addicted, leprous vampire (The Addiction; 1995)? Who could interest us, even for a moment, in the tired old questions of the family unit or the individual? Who could continue to arouse in us a desperate faith in sacrifice and love, unless they were almost autistic, completely crazed, haunted figures within films that cultivate advanced arguments concerning the need to destroy all filmic forms?

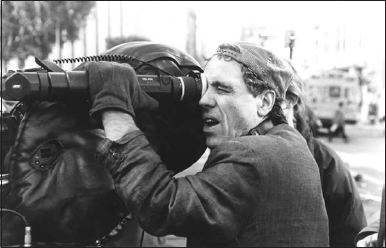

Ferrara was born on 19 July 1951 to an Italian American father (who turned from being a bookmaker to a stockbroker) and an Irish American mother. He is the youngest of six children, with five sisters. The Esposito family (renamed Ferrara by Abels grandfather after he emigrated to the United States) originates in Salerno, south of Naples. Ferrara studied at the Sacred Heart Catholic School in the Bronx: You were in, like, the front row and there was this giant crucifix, about eight feet tall, dripping blood. Ferrara returned to New York to study cinema at the State University of New York at Purchase and made a series of very short films (one or two minutes each) on Super 8 and sixteen-millimeter, devised as protests against the Vietnam War. As part of his studies he spent a year in Britain, where he participated in his first professional thirty-five-millimeter shoot for the BBC. Then he returned to New York and reunited with St. John; together they started writing and making films and playing music.

Next page

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.