STANFORD STUDIES IN JEWISH HISTORY AND CULTURE

EDITED BY Aron Rodrigue and Steven J. Zipperstein

Jewish Spain

A Mediterranean Memory

Tabea Alexa Linhard

STANFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

STANFORD, CALIFORNIA

Stanford University Press

Stanford, California

2014 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University.

All rights reserved.

This book was published with support from the Department of Romance Languages and Literatures and the Program in International and Area Studies at Washington University in St. Louis.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system without the prior written permission of Stanford University Press.

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, archival-quality paper

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Linhard, Tabea Alexa, 1972 author.

Jewish Spain : a Mediterranean memory / Tabea Alexa Linhard.

pages cm (Stanford studies in Jewish history and culture)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8047-8739-0 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. Jews, SpanishHistoriography. 2. SephardimHistoriography. 3. JewsSpain History20th century. 4. Collective memorySpainHistory20th century. I. Title. II. Series: Stanford studies in Jewish history and culture.

DS135.S7l73 2014

946'.004924dc23

2013047791

ISBN 978-0-8047-9188-5 (electronic)

Typeset by Bruce Lundquist in 10.5/14 Galliard

To Adolf Linhard, 19021954,

Melanie Linhard, 19051979,

and Karin Linhard, 19442007

In Memoriam

Contents

Acknowledgments

Like the stories that families tell over and over again, this book came together with the help of many voices; like the stories that families tell, the book has many flaws. I was only able to complete this work thanks to all those who helped me finish it; the responsibility for its shortcomings is mine alone.

My gratitude goes to my colleagues who read earlier and much rougher versions of the different chapters: Nancy Berg, Erin McGlothlin, Rebecca Messbarger, Joseph Schraibman, Michael Sherberg, and Harriet Stone. Daniela Flesler and Adrin Prez Melgosa have been amazing collaborators and wonderful readers. I am especially grateful for Andrew Bushs generous, intelligent, and thorough reading of the entire manuscript.

At Washington University, I would like acknowledge the support I received from the Department of Romance Languages and Literatures and the Program in International and Area Studies. Tim Parsons provided invaluable advice and support on all things international and interdisciplinary, and beyond.

Generous grants for summer research from Washington University have helped me complete my research. Collaboration with different working groups has greatly enriched and invigorated my work over the years, especially the Mediterranean Studies research group at Duke University and, at Washington University, the reading group on Transnational Approaches to Postmemory and the Research Cluster on Migration and Identity. Beyond my home base in St. Louis, I need to thank Sebastiaan Faber, Dalia Kandiyoti, Jo Labanyi, Jordana Mendelson, and Teresa Vilars. My students, who provided me with insightful questions and fresh perspectives, have been a great source of inspiration.

In 2010 I had the good fortune of participating in the Summer Research Workshop on Sephardic Jewry and the Holocaust at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museums Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies, which contributed significantly to the development of the research presented in this book. I would like to thank USHMM, especially Leah Wolfson; the seminar leaders, Aron Rodrigue and Daniel Schroeter; and the seminar participants for helping me think about parts of the world I barely knew how to place on a map before our seminar.

I am very grateful to Norris Pope, Stacy Wagner, Friederike Sundaram, Laura Kenney, and Carolyn Brown at Stanford University Press for helping me make this book a reality, and to Aron Rodrigue and Steven Zipperstein for believing in this project and making it part of the Stanford Studies in Jewish History and Culture series.

The years since I first started thinking about this book have been tumultuous, filled with moments of both immense joy and profound sadness that I shared with Silvia Ayuso, Cindy Brantmeier, Amy Sara Carroll, Daniel Chvez, Mara Devant, Jutta Gsoels-Lorensen, Asimina Karavanta, Anthony Kirk, Stephanie Kirk, Mara Fernanda Lander, Desire Martn, Nina Masot, Laura Medem, Margarita Muoz, Derek Pardue, Mauricio Tenorio, and Selma Vital. Sat Inder Singh Khalsa, Numancia Rojas, and Gigi Werner, my gifted teachers, have helped to keep things in perspective.

I would not have been able to complete even a single sentence without Guillermo Rosas, Emilio Rosas Linhard, and Aitana Rosas Linhard. Aitana told me recently that she did not understand why I was thanking her and her brother in the books acknowledgments, because, so she claimed, I did not do anything. I trust that one day she will understand how much she and Emilio do for me every day. Guillermo helped me in more ways that can ever be put into words, and I need to thank him for so much more than his tolerance for my obstinate use of inferior software products. But la nit es morta i ja s fa clar.... Thank you.

Curiosity about the lives of Melanie and Adolf Linhard inspired this book, and I thank Isabel Linhard de Hoffmann, Mirjam Mahler, and Jos Linhard for their stories, their relentless support for all my endeavors, and their love. And finally, I thank Karin Linhard, for everything.

appeared in the articles The Maps of Nostalgia: Juana Salaberts Veldromo de invierno, Revista Hispnica Moderna 60:1 (June 2007): 7293, and Surviving the Holocaust in Sepharad: Trudi Alexys Story, History & Memory 22:2 (FallWinter 2010): 97126. I am grateful to the journals anonymous readers and editors.

Introduction

Ask the Mediterranean

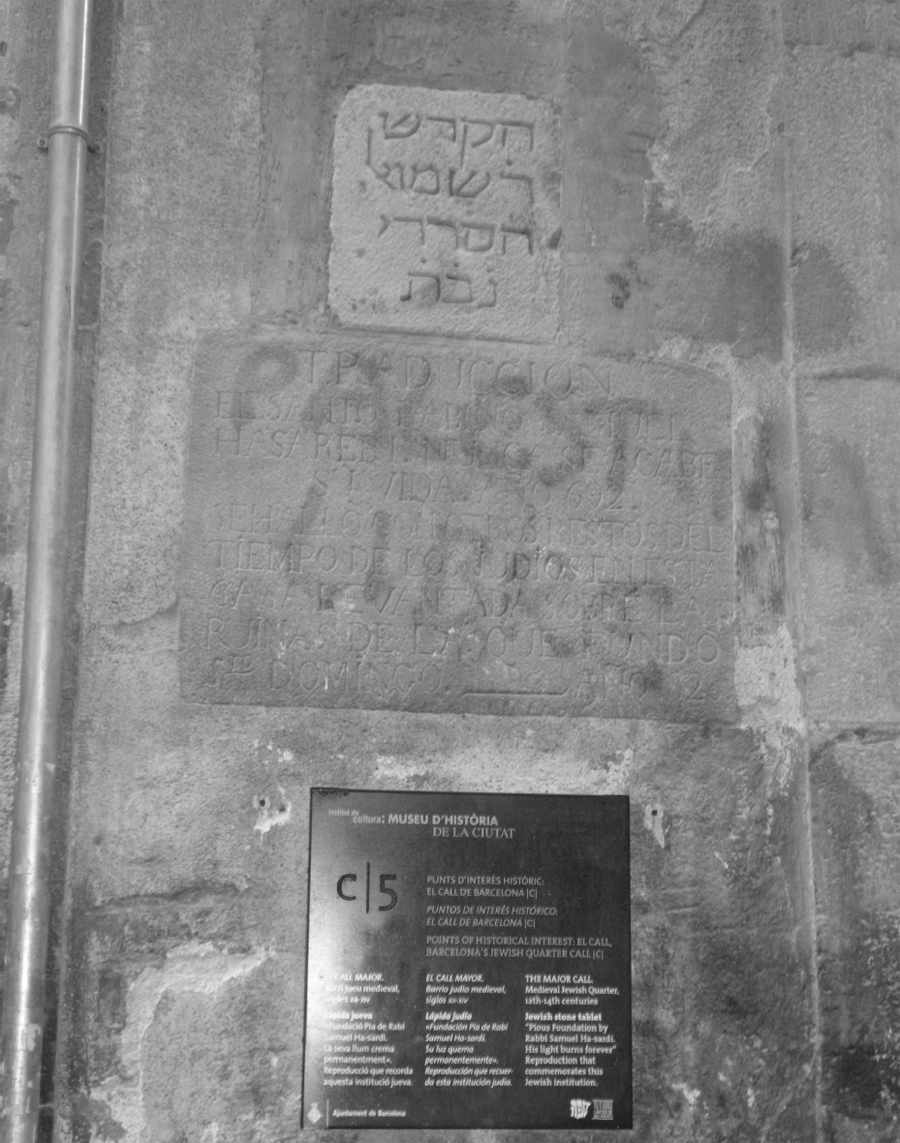

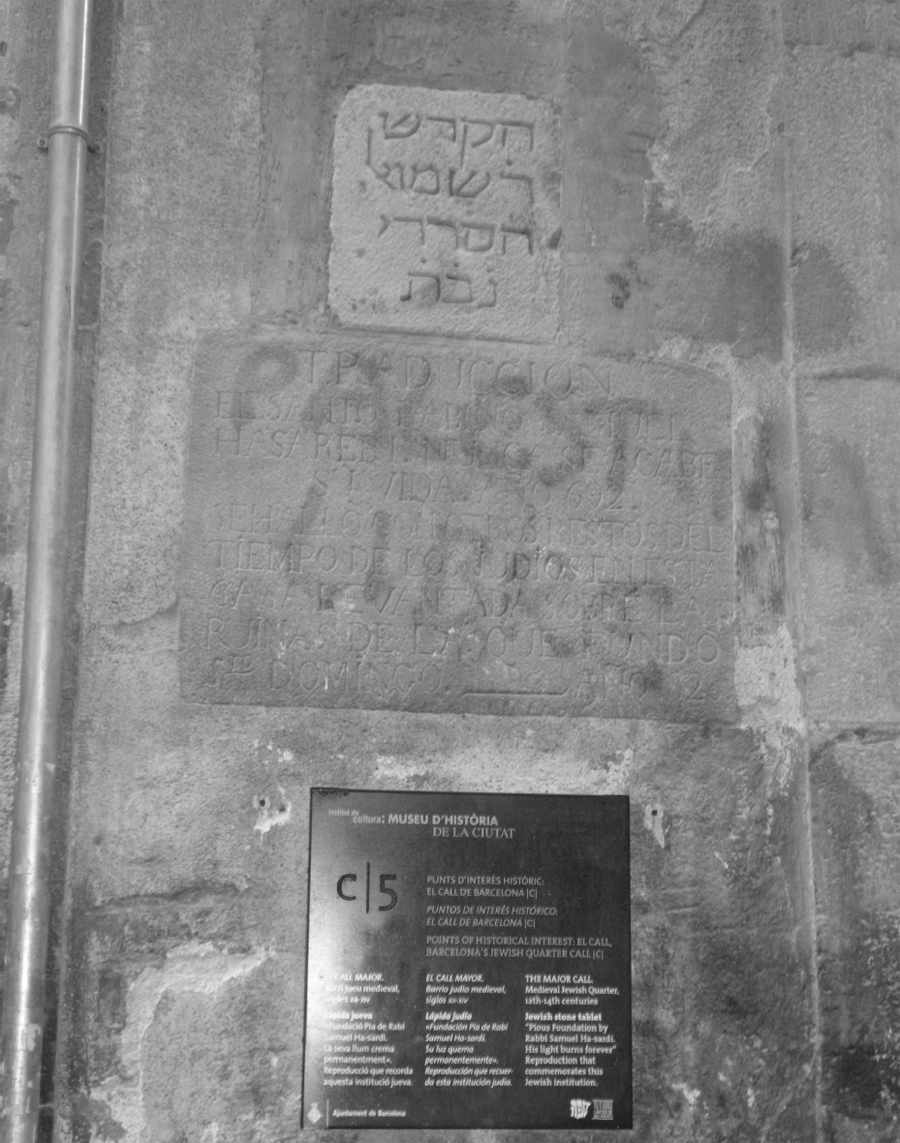

One of the most emblematic locations in Barcelonas medieval Jewish quarter, El Call, can be found at the corner of Marlet and Sant Ramon in the heart of the citys Gothic quarter. Three plaques are affixed to the walls of the house located at 1 Carrer de Marlet, a building that was restored in 1820. The first plaque, with a Hebrew inscription, is a copy of a plaque from the early fourteenth century, now kept in Barcelonas history museum, Museu dHistria de Barcelona (MUHBA). The second features an inaccurate translation of the Hebrew inscription. The owner who commissioned the nineteenth-century restoration was probably responsible for encasing the original plaque inside the outer wall of the building and placing the panel that contains the translation.

The replica of the original plaque from the fourteenth century was vandalized: a close look at the plaque with the translation reveals traces of the words Palestina Libre, written diagonally across the text. Even though the graffito has been removed and the words are now barely visible to the naked eye, their presence can still be detected in

Figure 1.1 Carrer de Marlet, Barcelona 2009. Courtesy of Tabea Alexa Linhard.

Figure 2.1 Carrer de Marlet, Barcelona 2013. Courtesy of Jos Linhard.

The different forms of writing and rewriting on these plaquesincluding the actual fourteenth-century inscriptions, the attempts to recover the memory of a population absent in the nineteenth century, the protection of Jewish heritage with the help of historical markers, and even the defacement of symbols of the past in a present-day struggleconjure up the main themes of this book.

Next page