Acknowledgments

I am honored to have had many fine mentors who have nurtured my passion for evolution, ecology, conservation, and the biological diversity of California. In no particular order these friends and mentors include George Corson, Doug Alexander, J.P. Smith, Bob Patterson, Ledyard Stebbins, Richard Mack, Rebecca Sharitz, Steve Edwards, Frank McKnight, Howard Latimer, Norm Ellstrand, Phyllis Faber, Jim Hamrick, Colin Hughes, Roger Lederer, and Wilma Follette. The friendships of Lily and Kader Anouche, Carla DAntonio, Debra Ayres, Sue Jensen-Pollard, Kate McDonald, Charli Danielsen, Barbara Leitner, Deborah Jensen, Laura Morelli, Ann Bernadette, Chris Lozano, Marilyn Tierney, Tim Messick, Adrienne Edwards, Dawn Wilson, Doug Kain, Cindy Phelps, Ray Carruthers, Ellen Clark and the Third Avenue and Bunco gangs have benefited me greatly at various points in my life and in one way or another helped me to finish this book. Nothing I do would be possible without the unending support of my husband, Jim Eckert. Thanks go to my many family members for supporting my academic endeavors but especially Mary Huff and Nellie Huff, without whom I would have not been able to attend college. William G. Huff instilled in me an appreciation for Californias rich history at a young age and provides some of the illustrations here. I thank the many enthusiastic and insightful students with whom I have been fortunate to interact over the past twenty years but particularly the dedicated graduate students; all have enriched my life and understanding of the biology of California.

Special thanks to those brave souls who provided comments on earlier versions of this work: Jay Bogiatto, Don Miller, Bruce Baldwin, Karen Burow, Andy Simpson, and especially John Avise, Peter Raven, and Arthur Shapiro. Chuck Crumly and Blake Edgar provided encouragement to complete this project and are much appreciated. California State University, Chico provided support to complete this work via a sabbatical.

PART I

Geologic And Organismal History

1

Introduction

What can we do with the western coast, a coast of 3,000 miles, rockbound, cheerless, uninviting, and not a harbor on it? What use have we for such a country?

Daniel Webster, 1845

The geographic province we now call California was and in some places remains every bit as rugged and inhospitable as Webster described. The geographic parameters preventing extensive European expansion before the nineteenth century are also the landscape on which the diverse flora and fauna of this region have evolved. The goal of this book is to examine and interpret the evolutionary history of the biota in California in a geologic context, as well as subsequent patterns in regional diversity that have emerged across combined phylogenies. A number of phylogeographic patterns have indeed emerged; some previously identified are expanded here in depth, and some new patterns are recognized. A survey of the phylogeography of the flora and fauna of Californias diverse biota is organized by major organismal groups, and these patterns provide the context in which to ask further questions about evolutionary diversification in an area defined by both physical and political boundaries. Comparing patterns of many organisms provides the evidence needed to construct questions that are narrower than those previously posed about the colonization of taxa extant in California. Ultimately, this review provides a context for landscape-level conservation efforts throughout the biogeographic provinces that roughly define the state of California.

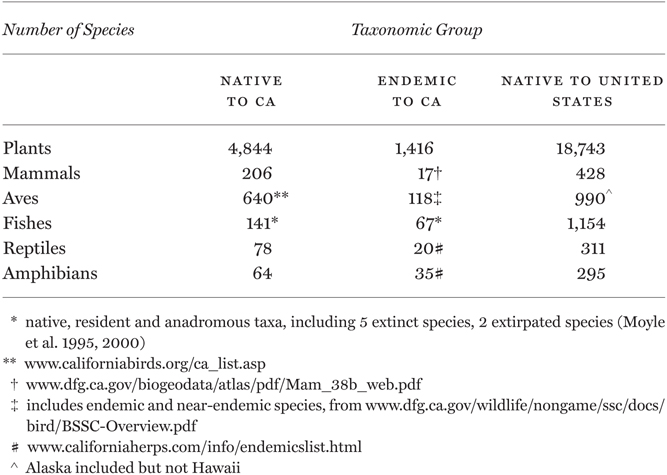

Table 1.1 Number of species native and endemic to California (~411 k km2) compared to number of species native to the United States (9.83 M km2) All 50 states included

There are few places in the world that rival California in both topographic and biological diversity over similarly sized geographic areas. The state of California encompasses 411,015 km2 and is 1,326 km long from corner to corner (Donley et al. 1979; Kreissman 1991). Plant communities range from Mesozoic coniferous forests along the north coast with rainfall of over 2,500 mm/year to halophytic communities in Death Valley with less than 3 mm/year of rain. In the northern Coast Ranges, an additional 200 mm/year of precipitation is added in the form of fog drip (Azevedo and Morgan 1974). California contains the highest peak in the conterminous United States (Mount Whitney, 4,406 m) and the lowest elevation in North America at Death Valley (-86 m), not more than 129 km apart. Each biogeographic region is remarkably heterogeneous in terms of topography, climate, and biological and geologic history. The diversity of species occurring within the political boundary of California cannot be rivaled in North America (Table 1.1), and Conservation International has recognized California as a globally important biodiversity hotspot (Myers et al. 2000).

Biogeographic studies of California are often focused on the California Floristic Province; however, for the purposes of colonization history from the south, north, east, and west, the biogeographic boundaries that define the California Floristic Province are expanded here to include areas beyond the states political boundaries: the Mojave Desert to the south and southeast; the western Sonoran (Colorado) Desert and northern Baja California; the Transverse and Peninsular Ranges and Channel Islands to the southwest; the Sierra Nevada and western Great Basin to the east; the Cascade and Klamath-Siskiyou Ranges to the north and northwest, including southern parts of Oregon; the Modoc Plateau to the northeast; and the Coast Ranges, Pacific Ocean, and continental shelf to the west and northwest. Because of migration patterns, marine mammals and migratory birds and fishes are included if the breeding portion of their life cycle occurs in the California area. Somewhat arbitrarily, groups not included in this monograph are molluscs, noninsect arthropods, algae, fungi, and members of the Archaea and Bacteria domains. Although there is some literature on these groups, in particular arthropods other than insects and other marine invertebrates, it was not feasible to include the entire biota. Organization within each chapter is roughly from north to south and old to young, dependent on the literature available for each clade.