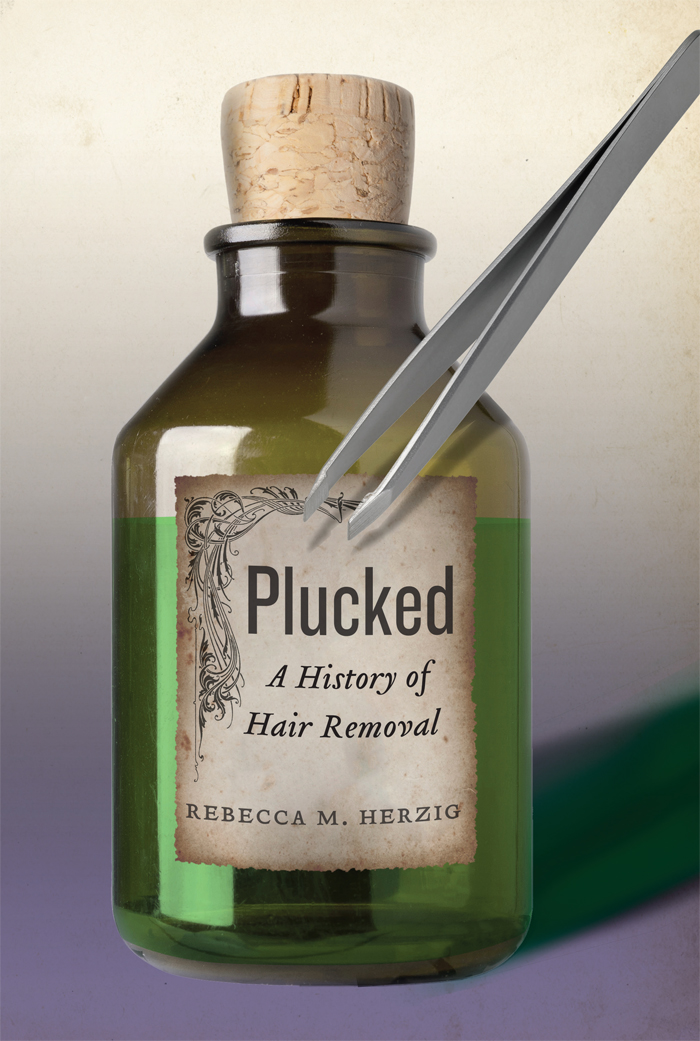

PLUCKED

PLUCKED

A History of Hair Removal

REBECCA M. HERZIG

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York and London

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York and London

www.nyupress.org

2015 by New York University

All rights reserved

References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Herzig, Rebecca M., 1971

Plucked : a history of hair removal / Rebecca M. Herzig.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4798-4082-3 (hardback)

1. HairRemovalUnited StatesHistory. 2. HairSocial aspectsUnited StatesHistory. 3. Body hairSocial aspectsUnited StatesHistory. 4. Human bodySocial aspectsUnited StatesHistory. I. Title.

RL92.H49 2015

617.4779dc23

2014027535

New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. We strive to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the greatest extent possible in publishing our books.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Also available as an ebook

For Jill Hopkins Herzig

Contents

INTRODUCTION: NECESSARY SUFFERING

IN THE CLOSING months of 2006, representatives of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) traveled to the internment facility at Guantnamo Bay run by the U.S. Department of Defense. There, the representatives conducted private interviews with fourteen high value detainees held in custody by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), in accordance with the ICRCs legal obligation to monitor compliance with the Geneva Conventions. Their resulting forty-page report on detainee treatment, sent to the acting general counsel of the CIA in February 2007, concluded that the totality of circumstances in which the detainees were held amounted to an arbitrary deprivation of liberty. Other aspects of the detention program constituted cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment, while in many cases the combined treatments to which the detainees were subjected constituted torture. The report devoted a separate discussion to each of the main elements of detainee abuse, including beating and kicking, prolonged shackling, confinement in a box, and deprivation of food.

Listed among these elements of abuse was another category: hair removalor, as the reports authors termed it, forced shaving (

In the searing debate that erupted around American treatment of detainees at Guantnamo, forced hair removal played an uncommon role. Critics of U.S. detention policies generally ignored the shaving altogether, instead focusing their condemnation on the use of waterboarding (suffocation by water). A Washington Times editorial, citing the Time magazine report, characterized the treatment of Guantnamo detainees as unpleasant:

[I]nterrogators did a number of unpleasant things to al Qahtani to get him to talk. These included shaving

Fred Barnes, executive editor of the Weekly Standard, summarized the mood among the Bush administrations supporters when he concluded that there have been FBI reports of rough treatment [at Guantnamo], but nothing I would consider torture. Although the International Committee of the Red Cross, Human Rights Watch, and detainees themselves repeatedly characterized beard removal as a violation of religious belief, personal dignity, and international treaty obligations, opponents and defenders of U.S. detention policy alike generally regarded forced shaving as a minor footnote to the nations larger war on terror.

Figure I.1. Table of contents from a 2007 Red Cross report on the treatment of U.S.-held detainees at Guantnamo Bay, noting the use of forced shaving.

The striking unity of opinion among Bush administration supporters and critics on the insignificance of forced shaving, particularly when juxtaposed with the divergent judgment of the ICRC, raises a number of questions. When exactly does a practice cease to be merely unpleasant and become cruel, inhuman torture? What distinguishes trivial nuisances from serious problems? Who gets to determine the parameters of true suffering, and of real violence? Such questionsmatters of knowledge and power, privilege and exclusion, life and deathanimate this book, a history of hair removal in the United States from the colonial era to the present.

At first glance, hair removal may seem an odd subject for such rumination. The treatment of body hair, like incessant celebrity diet updates or major league sporting news, could easily be considered one of those annoying tics of contemporary American culture best ignored. The whole topic of body hair, I have learned, strikes many people as not merely tedious but also uncouth, even downright repulsive. Several previous reviewers of this work suggested that hair removal is simply too repellent to merit scholarly attention.

It is not my intention to try to persuade readers otherwise. Although, as we shall see, hair removal has preoccupied political thinkers in the United States from Thomas Jefferson to Donald Rumsfeld, has shaped practices of science, medicine, commerce, and war, and has elicited breathtaking levels of financial, emotional, and ecological investment, this book does not try to argue that body hair is in fact more consequential than previously recognized. To do soto assert, say, that forced shaving is actually more torturous than waterboardingwould simply flip existing presumptions of value. My aim here is instead to illuminate the historical contingency of such assertions themselves. Delving into the history of personal enhancement, Plucked excavates the surprisingly recent development of seemingly self-evident distinctions between the serious and the unimportant, the necessary and the superfluous.

In the United States, those classifications have long served to segregate bodies into distinct sexes, races, and species, and to delimit the numerous rights and privileges based on those distinctions. Assessments and treatments of body hair also have served to define mental instability, disease pathology, criminality, sexual deviance, and political extremism. Some classifications have been codified in diagnostic criteria, bureaucratic regulations, or technical standards; others remain tacit understandings, held fast by emotion and habit. Throughout, the maintenance of such segregations and classifications has required labor, physical and emotional laborthe often grubby, painful chore of separating hide from flesh. By examining that labor more closely, we might better perceive the implicit values suffusing social life.

OF PARTICULAR CONCERN here are ideas about suffering. In the United States, those consequential moral and legal standardse.g., does the treatment of detainees at Guantnamo constitute torture?have long been established through recourse to the natural order of things, as discerned by scientific and medical experts. Battles over whose suffering gets to matter have been waged, in large part, over who is authorized to speak about natural facts. In the eighteenth century, for instance, the pronouncements of bodily deficiency made by eminent ethnologists and naturalists helped to buttress the political disenfranchisement of the continents indigenous peoples. In the nineteenth century, the arguments for the separate, distinct origins of races offered by physicians and anthropologists of the American School were summoned to defend the institution of slavery. More recently, the Behavioral Science Consultation Teams deployed at Guantnamo