Timber-frame barn, on the way out, near Bromyard, Herefordshire (photo: P.A. Rahtz).

While the building totters, various agents like to help it on its way: people can always spot a ruin and love to fiddle with it. An Anglo-Saxon church that was falling down at Moreton on the Hill in Norfolk provided an intriguing stage set for these final years of a redundant building. Ivy and creeper encircled its round tower, slowly pulling it down by inserting tendrils and gouging out the soft mortar. Rats and mice widened every hole. Birds flew in and out of the roof-space and nested there. Inside, the ceiling was splitting and dropping down on the floor in slabs of plaster. The first plants were gaining a purchase in the cracks in the floor and in the wet patch inside the baptismal font. And someone had been attracted to this deserted romantic hideaway possibly the homeless, but more likely the very young: no-one can modify a space as thoroughly as children building a den. Here they had pushed the pews against the north wall and lifted the font cover with its big iron spike and placed it at the east end where the altar was. Then they placed the chairs around the spike in a semi-circle. This is not how a church was used of course, and if the picture froze like this and sank back in this configuration into the earth, future archaeologists would deduce that they had found the ritual centre of a coven of spike worshippers.

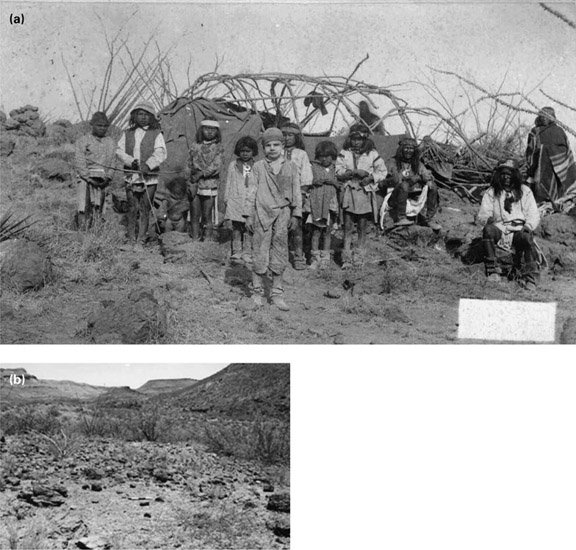

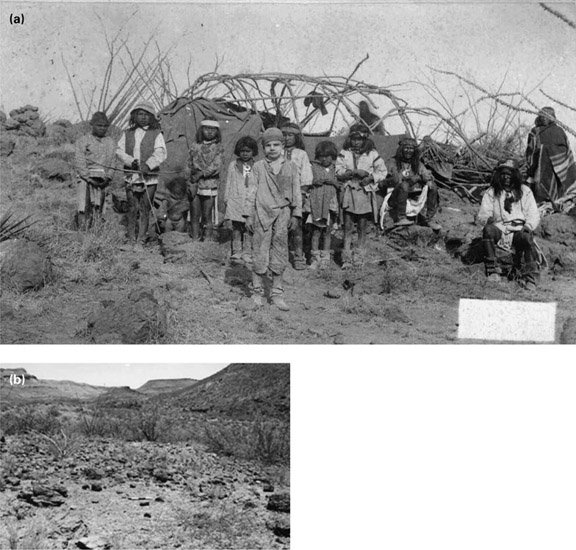

Some human sites, each with its own contemporary drama, leave next to nothing on the ground. shows an example from Mexico, a photograph taken in 1886 of one of Geronimos last camps before his surrender at Los Embudos. This wickiup

Geronimos wickiup (a), and prehistoric stances left by shelters of the kind in the same terrain (b) (Arizona Historical Society).

was a shelter formed among rocky boulders out of branches and cloth. When such places are later dispersed by wind and scavengers there is nothing much left but a little oval clearing among the stones or, if it got burnt down, a round patch of ash and partly burnt wood, like a bonfire, miles from anywhere. These ephemeral traces provide a poignant analogue for many millions of barely detectable dwellings built in the course of eventful lives throughout prehistory.

What archaeologists encounter in the ground is the end product of stories like this, stories of loss, decay and abandon. We will meet many examples in this book, but the colour plates offer a taster of their prodigious variety. Underneath the topsoil of a ploughed field, the doings of earlier people show as sets of spots and stripes (Colour Plate 1a). In well-frequented places, the debris builds up and lies deep, layer on layer (Colour Plate 1b). Modern instruments, like aerial cameras or radar, can sometimes sense these things before you see them (Colour Plate 2), but they become clearer when the soil comes off. Underground, while most structures are wispy traces, others are still robust with mortared walls and mosaic floors (Colour Plate 7). Like buildings, our mortal remains also survive in very variable forms (Colour Plates 6ac). Some, like the inhabitants of Pompeii, are now just a void in the baked volcanic ash. In the bog bodies of northern Europe acid has eaten out all the bones, but the flesh is preserved, tanned like a great leather bag. In Egypt and Mongolia, bodies were wrapped up in cloth by their burial parties, and survive as mummies, fibrous and desiccated. For people buried on chalky soils, the flesh quickly goes, but the bones survive clean and sharp a white skeleton. On sandy acid soils, the bones disappear but the flesh may leave its signature on the grave floor a stain or a rounded sand-shape. The ingenuity of the modern excavator can conjure up a striking image from the most ephemeral of traces: as an example I show a leather chariot in a Chinese tomb, evoked in three dimensions from the surviving film of paint that once covered the now vanished timbers (Colour Plates 8ac).

Archaeological investigation starts here, with the pieces of the past, lifes disjecta membra , the stuff. This is what we study. Making sense of this structured dirt, this materiality, is what gives us our mission, and our first task is to appreciate why we have what we have. All these cultural remains belong to people who deserve a history, but they do not equally leave us one. Some build to last, others build for the moment. Some seek immortality by wrapping up mummies and placing them in enormous tombs, others throw bodies deliberately or carelessly into bogs, or into holes in the ground. Other people die in accidents, never to be found or commemorated. Some take a lot of trouble to defeat time, and others do not. The survival of things is also clearly dependent on the type of soil in which things are buried. Chalk well-drained and alkaline is kind to bone; sand, well-drained and acid, is not. Anaerobic conditions, i.e. deposits that exclude air, like a bog, inhibit microbes so that organic materials are preserved. But the acid still dissolves the minerals, like the calcium salts of which bone is made. Under the ground, things are never alone for long. Humic soil is a mass of busy micro-organisms, digesting everything. Worms swallow the soil and spit it out, over and over again. Their tireless mixing raises the ground surface, until it climbs over the great flat stones of megaliths, buries Roman mosaics, creeps up the sides of stone crosses and over the steps of medieval churches. Beetles, rats and dogs like to dig and rummage in bodies. Pillagers dig them up to take the grave goods. Farmers plough the graves, rubbing down the first 25cm and mixing it up with the ploughsoil. Even when archaeological sites are deserted, they do not entirely die. They have a long and varied afterlife in which plants, animals and humans archaeologists eventually among them will intervene.