Structural Appraisal of Traditional Buildings

Structural Appraisal of Traditional Buildings

Patrick Robson

Consultant in Structural Engineering and Dispute Resolution MSc, CEng, FConsE, MAE, FIStructE, MICE, MaPS

First published in 1991 by Gower Publishing Company Ltd.

Published by Donhead Publishing Ltd 2005

Published 2015 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informabusiness

Patrick Robson 1991, 2005

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

ISBN 13: 978-1-873394-68-7 (hbk)

ISBN 13: 978-1-315-79376-4 (eISBN)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Robson, Patrick, 1941

Structural appraisal of traditional buildings. 2nd ed., rev.

1. Building inspection 2. Buildings Testing 3. Structural stability 4. Structural failure

I. Title

690.2'1

ISBN 1873394683

Typeset by Aarontype Limited

Contents

This book has been substantially rewritten for its second edition, with the object of broadening its scope as well as bringing it up to date. New topics include structural behaviour, building types, dating and initial appraisal.

I hope the book is of interest to all professionals who are concerned with the causes of structural defects, their diagnosis, and the structural alteration and preservation of traditional buildings.

The scope of the book is limited to traditional building which, for this purpose, means the various forms of timber and masonry construction that have been commonly used in the United Kingdom from medieval times to the present day. It could be argued that modern cavity-wall construction should be excluded but, as we are discussing structural performance in isolation, it would be illogical to deal with solid walls and not cavity walls. Modern steel framing and reinforced concrete are excluded. Their structural performance is not adequately explored by the simple methods outlined here, although there is brief mention of the early, simple uses of metals.

The book discusses each of the basic needs of structural appraisal, which are as follows:

- An understanding of how traditional buildings behave as structures, and knowledge of the main types of building and their foundations ().

- A knowledge of the many causes of damage. Without this basic reference, at least some diagnoses will be wrong, because if a cause cannot be imagined it will not be considered ().

- A range of techniques for testing all the potential causes of damage ().

- A method of interpretation. This ensures that the true cause(s) will be identified ().

- ties up a few important related matters.

I am grateful to Paul Mellor for producing most of the many illustrations from my rough early sketches. My wife managed the text and tables, and Dorothy Newberry turned the parts into a whole.

. I am grateful to them all. It is only fair to add that they did not have the opportunity to approve the final draft.

Part One

Introduction to appraisal

Chapter One

Principles

Structural appraisal has its own discipline, different from design. Like design, it needs an understanding of material behaviour, but its essence is detection. There are no formulae for detection, no theorems that deduce cause from damage. There are only methods for converging on the right answers. These methods require visual skills; written description cannot always do them justice and therefore illustrations have been included to leaven the text.

Where does the structural appraisal of traditional buildings fit within the general range of building inspections and surveys? Richard Oxley ( Survey and Repair of Traditional Buildings: A Sustainable Approach) lists the most common types as:

- Mortgage valuation

- Risk assessment - a basic evaluation made by mortgage lenders

- Commercial valuation

- Portfolio assessment

- Pre-purchase

- Vendors survey (Home Condition Report)

- RICS Homebuyer Survey and Valuation Report

- Building Survey and Condition Survey

- Structural Survey/Assessment

- Buildings in continual ownership

- Periodic condition inspection reports (e.g. Quinquennial Inspection Reports, such as those carried out by The National Trust and the Church of England.)

- Defect analysis investigations

- Damp and timber surveys

- Investigations into structural movement

- Schedule of dilapidations

- Feasibility studies

- Specifications for repairs

- Design for alteration

- Insurance claims (including the specification of repair for damage suffered)

- Energy assessments and ratings

- Grant aid applications

Two examples from Richard Oxley's list will be considered in this introductory chapter: investigation into structural movement; and design for alteration. These examples will outline the principles that should apply to structural appraisal.

Investigations into structural movement

Designers must equip new buildings to face uncertainties during their useful life; for design purposes, these uncertainties are codified. The designer refers to British Standard loading, approved details and regulations, and accepted margins of safety. There is no such guide for investigation into structural movement. The same codes cannot be applied in reverse because their uncertainties would get in the way, deflecting the enquiry off target. The object of investigation is to determine what has really happened. When this is known, the matters that are more important to the client - severity, prognosis and recommended action - fall into place.

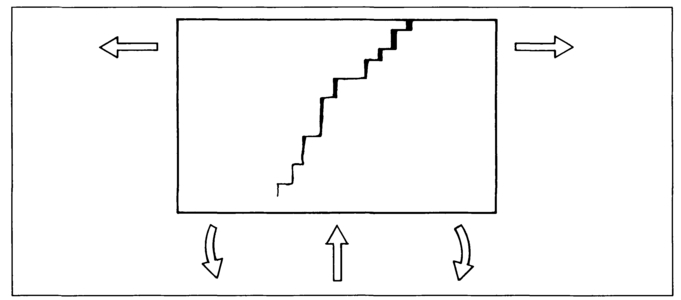

For damage to occur, something must have caused movement. It is that event which the investigation must first uncover. Later, the circumstances that could be criticized for aiding and abetting the event may be of equal interest, but they must not be allowed to confuse the detective work. For example, a gable wall may be described as 'lacking restraint' and that may well be correct, but if the wall had stood for a hundred years before succumbing to damage it would not be an adequate description of cause; neither would the description alone lead to a useful recommendation. The singular event must be identified first. The singular event could of course be a combination of movements, for example, thermal expansion and foundation settlement. A building may suffer from several problems, each with its own major cause; it is not usually difficult to recognize individual symptoms and to isolate each one.

cover foundation movement. In addition, we may need to consider thermal or moisture movement, as well as other potential causes related to the superstructure.