Copyright page

Copyright Ash Amin and Nigel Thrift 2017

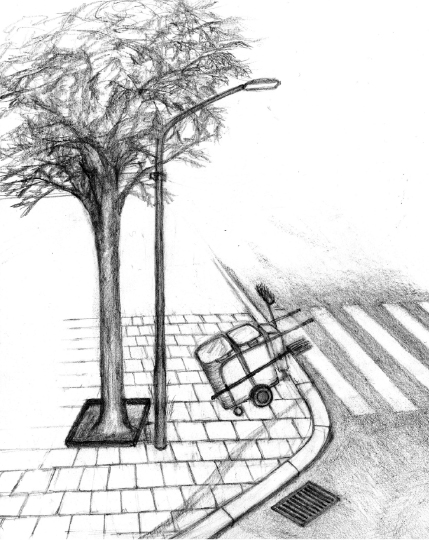

All images copyright Katarina Nitsch 2017

The right of Ash Amin and Nigel Thrift to be identified as Authors of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in 2017 by Polity Press

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

350 Main Street

Malden, MA 02148, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-0-7456-6425-5 (hardback)

ISBN-13: 978-0-7456-6426-2 (paperback)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Amin, Ash, author. | Thrift, N. J., author.

Title: Seeing like a city / Ash Amin, Nigel Thrift.

Description: Cambridge, UK ; Malden, MA : Polity Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016017516 (print) | LCCN 2016029541 (ebook) | ISBN 9780745664255 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 0745664253 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780745664262 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 0745664261 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781509515615 (mobi) | ISBN 9781509515622 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Cities and towns. | Sociology, Urban. | Human geography.

Classification: LCC HT119 .A49 2016 (print) | LCC HT119 (ebook) | DDC 307.76dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016017516

Typeset in 11 on 13 pt Sabon by Toppan Best-set Premedia Limited

Printed and bound in the UK by Clays Ltd, St. Ives PLC

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website:

politybooks.com

Acknowledgements

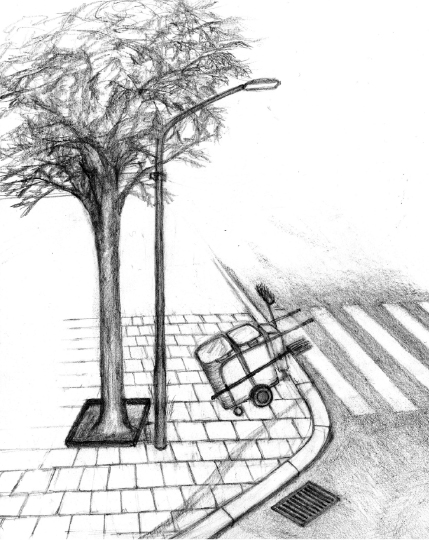

We are very grateful to Katarina Nitsch for agreeing to illustrate this book. Katarina, who draws human and nonhuman relations in the city, chose ideas in the text she was taken by. We left the choice of ideas and their exact locations to her, as we wanted to add an independent, visual, dimension to the book. We are delighted with the drawings. We also thank the three anonymous referees for their insightful comments on an earlier draft. Thank you too to John Wiley & Sons, Inc. for allowing us to republish parts of the article Space, which appears in The Encyclopedia of Geography: People, the Earth, Environment and Technology. (Excerpts reprinted with full permission.) Finally, we are indebted to Jan Parsons for painstakingly assembling the book from disparate chapters and bibliographies. The book's title Seeing Like a City has been used before, by Mariana Valverde, Saskia Sassen and Warren Magnussen. We borrow it here to encapsulate the worlding done by cities and the challenge to thought and practice posed by the ontology of spatial throwntogetherness, Doreen Massey's captivating term for urban process. Doreen, a friend and inspiration, tragically passed away as we were penning the last lines of the book.

Prologue

I want you to help me to find out what happened to us.

Ballantyne, 2013, p. 15

Corner

It takes satellite images and maps of flows to convey a sense of the world significance of cities. They light up and map out the densities of settlement, the traffic of inter-urban flow, and the dependencies of hinterlands near and far on cities. Meanwhile, less graphic scholarship reveals that a small number of urban titans now drive world economic prosperity and creativity, that their elites possess formidable national and transnational power, that states and militias increasingly target cities for geopolitical advantage, that human behaviour is shaped in the habits of metropolitan dwelling, and that the history of the Anthropocene is predominantly the history of urbanization. This research and scholarship presents cities as forcing houses: centres of creativity, competitive advantage and human fulfilment (Glaeser, 2011), as sites of democracy or revolution rekindled (Harvey, 2012; Merrifield, 2013; Douzinas, 2013), and as worldling sites that set a standard (Roy, 2014). It finds the urban everywhere, the tentacles of cities sustaining a new era of planetary urbanization (Brenner, 2014) and inter-urban networks and alliances driving global geopolitics and political economy (Taylor, 2013).

This book locates itself in this same genre of writing. But it is also a reconsideration to compensate for a tendency in this genre to erase the territorial in its keenness to emphasize urban globality, or to reduce the new urban centrality to foundational forces such as capital accumulation (Brenner, 2014; Brenner and Schmid, 2015), or the spatial agglomeration of firms, skills and institutions (Storper, 2013; Scott and Storper, 2015; Storper and Scott, 2016). Instead, as a counterweight, the book looks to the agency of another kind of urban assemblage the effects of things massed together that furnish the world through closely jaxtaposed or interwoven concentrations of humans, technologies and infrastructures providing much of the push. Our argument is that more than just spatial concentration is involved. It is the coming together of overlapping sociotechnical systems that gives cities their world-making power.

Our aim is to get to the citiness of cities; admittedly, a concept as elusive as the humanness of humans, with many possible configurations and arrangements. Cities are spatial radiations that gather worlds of atoms, atmospheres, symbols, bodies, buildings, plants, animals, technologies, infrastructures, and institutions, each with its own mixes, moorings and motilities, each with its own means of trading living, and dying. What form of distillation is possible without violating the character of cities as pluriverses, to borrow William James's (1977) phrase? It certainly cannot be one that reduces these pluriverses to systemic imperatives or spatial essences.

Instead, the distillation has to get close to the combinational machinery itself, for example, the summative force of many entities, networks and sociotechnical networks intersecting and colliding with each other (Farias and Bender, 2011; McFarlane, 2011; Lancione 2014; Batty, 2013; Sennett, 2013). This is the kind of synthesis we attempt in this book, focusing in particular on the agency of sociotechnical systems. Building on our earlier book (Amin and Thrift, 2002), we see the city as a machine whose surge comes from the liveliness of various bodies, materials, symbols, and intelligences held in relation within specific networks of calculation and allocation, undergirded by diverse regimes and rituals of organization and operation. We distil citiness down to the combined vitality and political economy of urban sociotechnical systems, which we believe define the modern city. Together, the arrangements of water, electricity, logistics, communication, circulation and the like, instantiate and sustain life within and beyond cities in all sorts of ways: allocating resource and reward, enabling collective action, shaping social dispositions and affects, marking time, space and map, maintaining order and discipline, sustaining transactions, moulding the environmental footprint. These arrangements are more than a mere infrastructural background, the silent stage on which other powers perform. The mangle of sociotechnical systems in a city is formative in every respect, regardless of its state of sophistication. This, at least, is our thesis.

Next page

Corner

Corner