Stephen Jay Gould

W.W.NORTON & COMPANY

NEW YORK LONDON

Copyright 1987 by Stephen Jay Gould

All rights reserved.

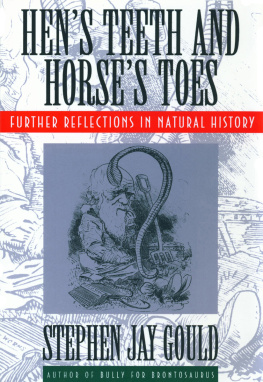

Drawings by David Levine. Reprinted with permission from The New York Review of Books . Copyright 19631987 Nyrev, Inc.

First published as a Norton 1988

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gould, Stephen Jay.

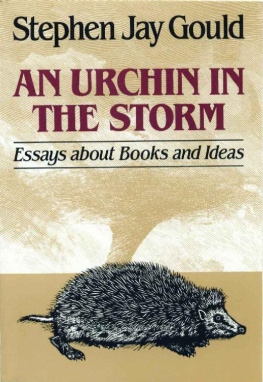

An urchin in the storm: essays about books and ideas by Stephen Jay Gould.

p. cm.

1. Biology. 2. BiologyBook reviews. I. Title.

QH311.G68 1987 87-21718

574dc19 CIP

ISBN 978-0-393-30537-1

W.W.Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W.W.Norton & Company, Ltd.

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street London WIT 3QT

From the heartland of vestigial American anglophilia

To my two favorite British intellectualsArab and Jew by origin.

E pluribus unum .

For Peter Medawar, a man of consummate bravery, penetrating intellect, unsurpassed joie de vivre , and unfailing encouragement to men of good will; and

For Isaiah Berlin, the polymath of our time, who once befriended a young scholar with no status at all, and who gave old Archilochus his biggest boost since Erasmus.

In appreciation for their inspiration but, above all, for their kindness.

Contents

Preface

T he U.S. Army Teaching Manual is a compendium of wise and practical advice from an institution that surpasses all others (probably even the public schools, since most kids retain some spark of interest) in its need to foist information upon an unwilling and unresponsive audience. This manual lists, as its first rule, never apologize. Yet I do not know how else to introduce a volume of book reviews (though my apology is only a tactical feint before the right cross of justification).

I once heard a speech by Herblock, addressed to aspiring journalists and dedicated to eradicating the notion that newspaper articles could be more than strictly ephemeral and eminently forgettable. He cited an old motto from the era before extra-duty plastic bags: yesterdays paper wraps todays garbage.

On the continuum from Rupert Murdoch to King James, old book reviews must, as a genre, fall at or very near the ephemeral end. A second argument against the preservation of book reviews lies in their central characterfor no literary activity is so despised and excoriated (often properly so) as the reviewers art. I picture several reviewers of my own books as passing a long future lodged between Brutus and Judas in the jaws of Satan. The famous quip of Max Reger to a music critic well illustrates the dubious propriety of reviewing as a general activity, the attitude of creative people to the genre, and the ephemerality (and place of final disposal) for its results: I am sitting in the smallest room in the house. I have your review in front of me. Soon it will be behind me. Yet the very vehemence of dismissal also indicateson the old Shakespearian principle of protesting too muchthat reviews are not so lightly ignored. Charles Lamb proclaimed, for critics I care the five hundred thousandth part of the tithe of a half-farthing. But why waste such emotional verbiage on an activity really accorded (if I calculate correctly) but one forty millionth of an old English penny in value.

Yet books are the wellspring and focus of our lives as scholars. Commentary upon such a source should, at its best, be expansive and enlighteninga sign of respect for a basic product. That so many book reviews are petty, pedantic, parochial, pedestrian (add your own ps and qs, querulous, quotidian, quixotic)so much so that they have folded what might be an honorable genre into their gripping nastinessstrikes me as a sadness that might not lie beyond hope of reversal. Why should articles of commentary on other books not lie within the domain of the essay?

To gain such a status as potentially worth preserving, such commentaries would have to forego what many take to be the primary charge of a book reviewto present a detailed account of the works content and merit. (Most books, after all, are ephemeral; their specifics, several years later, inspire about as much interest as daily battle reports from the Hundred Years War). Another type of book reviewone that uses another writers work as an anchor for discussing an issue of wider scopemight provoke an authors ire, but might also gain, by its generality, entry into the class of essays.

Since I am most moved by general themes, but find them vacuous unless rooted in some interesting particular, I have always tried to write book reviews in this broader style. I even dare to hope that some authors might be pleased to see their particular work used as a focus for general discussion, rather than reviewed by the traditional listing of likes and dislikes. (I am at least consistent in foisting upon others what I hope for myself. Among all reviews of my own books, I particularly cherish a long article, also from the New York Review of Books , on Ontogeny and Phylogeny written by the great British zoologist, J.Z. Young. He wrote a wonderfully perceptive essay on the relationship between embryology and evolution, but only bothered to mention that I had written a book about the subject in the last two paragraphs. Made me think (I am not being facetious) that I had done something worthwhile in choosing a meaty subject, long neglected. I would much rather be an interesting particular for an enduring generality than an item of, by and for itself and the moment alone. Verweile doch, du bist so schn .)

These essays are not quite so unmindful of their generating products as Young on ontogeny. We must believe that books, and their ideas, have an enduring meaning worth consideration after an actual title goes out of print (though nearly all discussed herein remain on the shelves of good bookstores, at least as paperbacks). Each of these chapters uses an individual book to pursue a general theme, but organizes its discussion as a critique of content. (I have also written some reviews in the more conventional mode of local judgmentbut these I have not included.) All but one of these essays originally appeared in The New York Review of Books . My deepest thanks to Robert Silvers, a great editor who makes fine (and even insistent) suggestions but who will not change a comma without consulting. I hope that these pieces follow his goal for a genre of general commentary rooted in the review of books.

My second rationale for this collection lies in the coherence that I (at least) detect among its disparate subjects. I didnt impose any theme as I worked piecemeal over a decade, but a judicious choice of titles by Bob Silvers combined with a personal, stubborn consistency of viewpointthe hobgoblin of small minds to be surecombined to record a particular view of nature and human life: the perspective of an evolutionist committed to understanding the curious pathways of history as irreducible, but rationally accessible.