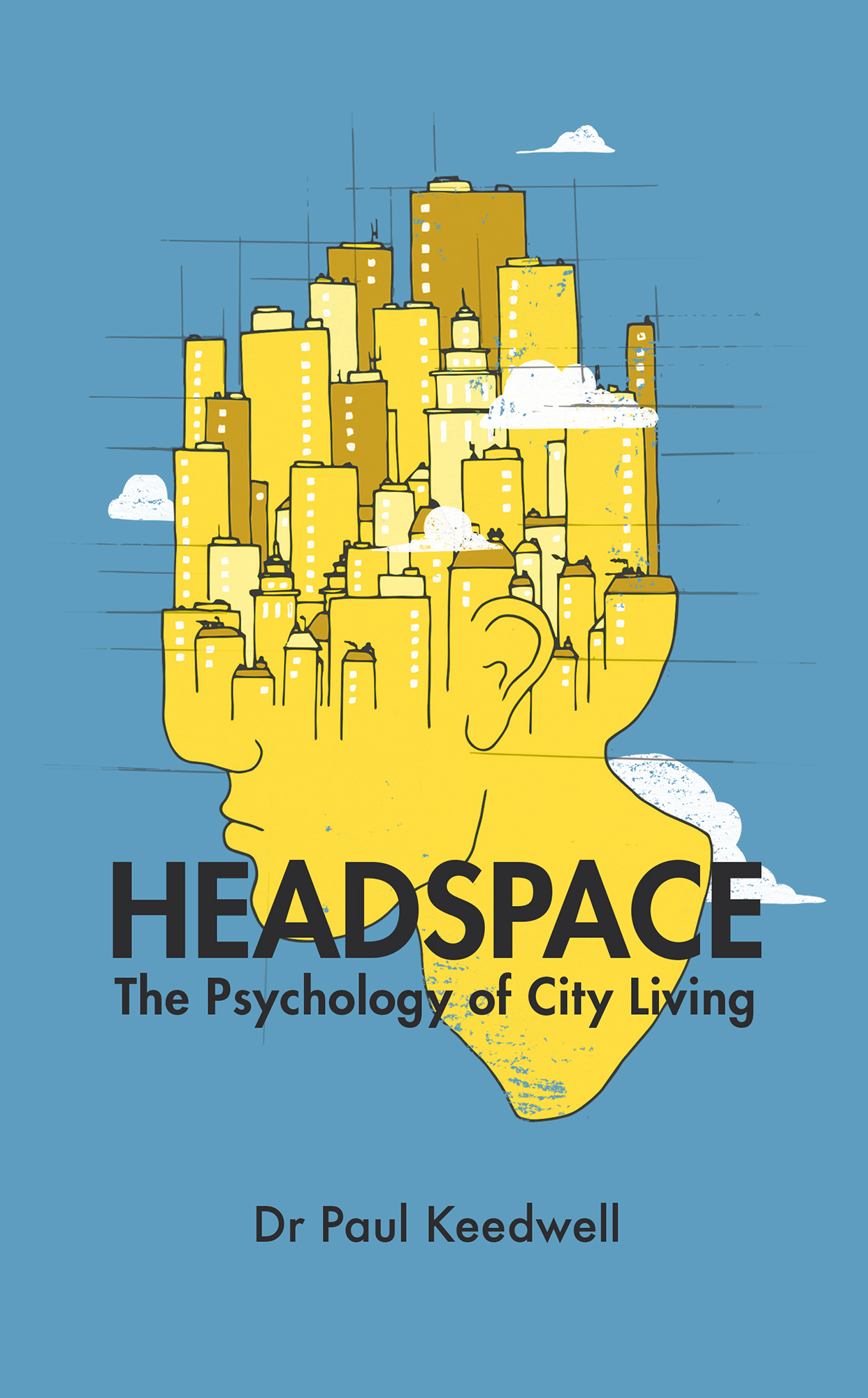

HEADSPACE

The Psychology of City Living

Dr Paul Keedwell

First published in Great Britain

2017 by Aurum Press an imprint of The Quarto Group

The Old Brewery

6 Blundell Street

London

N7 9BH

Quarto Publishing PLC 2017

Copyright Dr Paul Keedwell 2017

Dr Paul Keedwell has asserted his moral right to be identified as the Author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from Aurum Press Ltd.

Every effort has been made to trace the copyright holders of material quoted in this book. If application is made in writing to the publisher, any omissions will be included in future editions.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Digital edition: 978-1-78131-712-9

Softcover edition: 978-1-78131-611-5

2021 2020 2019 2018 2017

Contents

- Introduction:

The psychology of the city - Part One:

The Home, From Inside Out- Chapter 1

Refuge versus prospect - Chapter 2

Mystery and complexity - Chapter 3

Closure - Chapter 4

Nature in the home

- Part Two:

Home and Identity- Chapter 5

Status objects versus personal objects - Chapter 6

Space sharing - Chapter 7

The stamp of personality - Chapter 8

Tailor-made homes

- Part Three:

Neighbourhood- Chapter 9

Street life - Chapter 10

Protecting the territory - Chapter 11

The spirit of place

- Part Four:

High-rise Living- Chapter 12

Vertigo and other fears - Chapter 13

Making better high-rises

- Part Five:

Public Places: Places for Play- Chapter 14

Childs play - Chapter 15

Adults are kids, too: green spaces - Chapter 16

Recreational buildings

- Part Six:

The Workplace- Chapter 17

Open-plan? - Chapter 18

Self-expression

- Part Seven:

Healing Spaces- Chapter 19

A healthy atmosphere - Chapter 20

End of life - Epilogue

The ideal city

Guide

Introduction

The psychology of the city

How did it all go so wrong? We showed them how to do it.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (modernist architect)

More and more of us are living in cities. They can be stimulating, creative, inspiring places. As Samuel Johnson said, when a man is tired of London, he is tired of life. But cities are also stressful, and they can be alienating. Rates of anxiety and depression are higher in our inner cities than they are in the countryside.

Urban design has an important part to play in amplifying or minimising these threats to our well-being. How our homes, streets, neighbourhoods and public buildings look, and how they are arranged, matter. These are not just aesthetic preoccupations, they are important for our mental health. Good homes, neighbourhoods and public spaces improve our wellbeing by buffering against the stressful demands of a working day.

Most of the time we dont notice the effects of the environment on our mood because we are too preoccupied with the normal trials of life. But the built environment affects us nonetheless. As individuals and as city communities, we need to think more about how we can shape the world we live in.

I am a psychiatrist and a psychologist who has spent the last fifteen years renovating homes in London. When I studied the history of modern architecture, I developed the theory that trends in design had mirrored new evolutions in psychology: the understanding, via Freud and Jung, of unconscious drives (the home can be thought of like the womb, for example); the study of human conditioning (different environments trigger emotions from past experiences); social psychology (how buildings and neighbourhoods can be prosocial or alienating); cognitive psychology (how our attention and learning can be influenced by design); and evolutionary psychology (how natural selection has shaped our preferences for different aesthetics).

The scientific study of how buildings affect our feelings and behaviours is a niche subset of environmental psychology, best described as architectural psychology. There is a lot of information out there, but it is surprisingly absent from the syllabus of an average school of architecture, and there has been no attempt to synthesise it in a way that we can all understand.

Buildings, and the spaces between them, enrich or enervate our lives, affecting how we perceive, think and feel. It is up to us to make sure that they work for us. Developers often build life-sapping buildings, dictated by the interests of commerce. Government buildings are often dictated by cost-cutting. Architects and town planners like to think that they know people and therefore know what will make them happy, but they have made a lot of mistakes over the years, and they are still making them. Much design and planning is guided by a kind of empathic intuition rather than any scientific evidence. The esteemed architect might be more concerned to make an artistic statement than to design a space that people actually enjoy using. Architectural psychology is often just a secondary concern.

Rem Koolhaas, the world-famous Dutch architect, is known for his interest in the ever-changing, fragmentary nature of the urban metropolis, and in bigness in architecture. He has been involved in the planning of some of the megacities of China.

During an interview it was put to him that the Chinese practice of designing off-the-peg, high-rise blocks in under two days might lead to a less hospitable living environment. He replied: . And they can be miserable in anything, and ecstatic in anything. More and more I think architecture has nothing to do with it.

If Koolhaus is right if people are immune to their built environments then all we need is one-size-fits-all architecture and cities of monolithic, computer-driven buildings. This book is my attempt to prove him wrong especially when it comes to high-rise living.

People demonstrably prefer certain aspects of architecture over others. We prefer a room lit by two windows instead of one. We prefer to walk along a high street that has a human scale, rather than a road serving warehouses or megastores. We like to look out onto nature. We mostly prefer streets on the ground than in the sky.

Buildings can have short- and long-term effects on how we feel. Sometimes, a building is exciting when you first walk around it but causes stress over time. Some buildings encourage exploration and play. Some shut it down. Some encourage us to be sociable, others are alienating.