There are people I need to thank. Some never suspected they'd get caught up in a project like this one. That makes x-plus-me of us. But unpredictability makes the world go round.

Okay, fortunately the earth's steady rotation is utterly nonrandom and has nothing to do with unpredictability. Let's move on.

Earnest thanks to Gary Heidt at Imprint, and Lauren Mosko and Jane Friedman at Writer's Digest, for their perspicacity, their enthusiasm, and their hard work.

All respect and admiration for John Ol' Chumbucket Baur, Mark Cap'n Slappy Summers, and Dave Barry, respectively the founders and advocate of Talk Like a Pirate Day every September 19, blow fair or blow foul. What they began is a very good thing. I stand on the shoulders of giants.

Thanks to Jane Farnol Curtis and to her father's excellent legacy. Jeffery Farnol's pirate novels are among the great narratives of the sweet trade, and their author was one of the finest if not the finest writer of pirate dialogue in history.

There are hundreds of impressive places and events in this country that celebrate pirates and the maritime tradition. I've had the privilege of experiencing a few the Gasparilla Pirate Festival in Tampa, the New England Pirate Museum in Salem, the Pirate Soul Museum and the Mel Fisher Maritime Museum in Key West, the Pirate Walk in Newport, the Pirate Ring on the World Wide Web and I applaud all the rest for helping preserve a very unique, powerfully American, implausibly fascinating strand of history.

The mother of the small fat man who lives in my house is a land angel. She wrote this book with her infinite patience and support. I'd marry her a third time if solemnly called upon.

Finally, one of the proofs of God's existence is the trolley pirate. May his supply of unsuspecting tourists be steady, his fake-boarding forever be fake-terrifying. May all good things come to the trolley pirate.

Preface

On vacation, my beautiful wife and I drive from Miami to Key West (my left forearm cooking down to jerky under driver-window sun), park the car in a municipal lot, and leaving behind everything else, including a beach copy of Treasure Island hop onto a sightseeing trolley around the island.

I remember pieces of the tour pastel bungalows, a museum but not much else. Except this: We turn a corner. Out of nowhere comes a giant pirate racing after our trolley on foot, swinging a cutlass, screaming pirate epithets like we're stealing his treasure and feeding it to his dying mother.

He hauls after us for a block or so. Then he stops, stares a moment, and walks away. Cutlass dragging after him. No explanations.

On our last day, we happen into a costume shop. The person behind the desk looks familiar. We've seen him before his elaborate pirate regalia is a hint. It's the trolley pirate. He confesses: Several times a day, he charges out the door after tourists, harasses them nine different kinds of pirate-like, then calmly steps back into the shop and resumes his business.

I think to myself: That's got to be the best job in the world.

Then I think: If only there were some kind of manual.

Introduction

THE POINT OF THE PRIMER

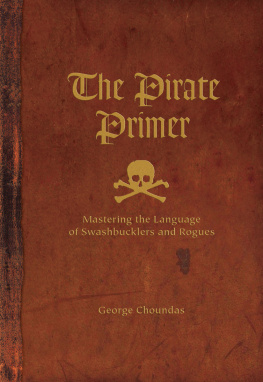

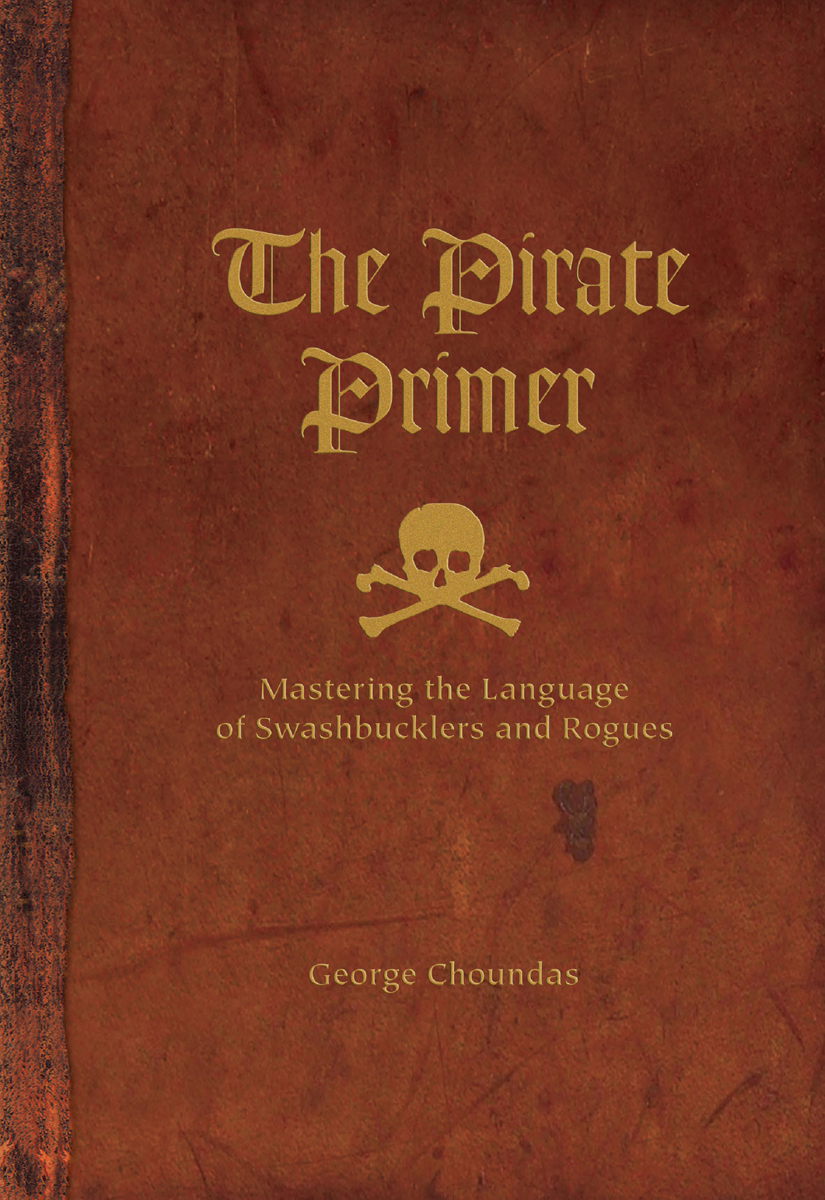

You hold in your hands the world's only complete guide to the pirate language.

But this begs the question: Is there such a thing as a pirate language?

The short answer is yes. If one were to take the statements made by or attributed to English-speaking pirates in historical accounts, literature, film, and television and then distill and identify all those words and patterns that are distinctive from or used with disproportionate frequency as compared with modern English, the resulting compilation would be a freestanding pirate language. This is precisely what the Primer does.

The long answer is also yes, with stops along the way. The term language suggests a uniform way of talking. But not every pirate speaks in the same way. Not every pirate uses the same words or pronunciations. Not every pirate sounds like Long John Silver (played by Robert Newton) in Walt Disney's 1950 production of Treasure Island or hails from Bristol or the southwestern parts of England. Many or most of the pirates in film, television, and literature are obviously colorful stereotypes, not authentic representations of the diverse breed of criminals who actually sailed the seas. In his book Under the Black Flag: The Romance and the Reality of LifeAmong the Pirates, David Cordingly writes of the pirate we all know: Over the years fact has merged with fiction. The picture [of pirates] which most of us have turns out to be a blend of historical facts overlaid with three centuries of ballads, melodramas, epic poems, romantic novels, adventure stories, comic strips, and films. (xiii-xiv)

The truth, however, is that heterogeneity is a feature of every language. A New Yorker's vowels are generally not the same as a San Franciscan's, and the vocabulary of a college graduate in either city will likely vary from that of the high-school drop-out living across the street. Pirates similarly hailed from different places, ethnicities, and educational backgrounds (see introduction to Chapter 17: Pronunciation), which makes the consequently diverse elements of their speech all the more interesting.

Pirate speech varies even among pirates in the same company: Treasure Island's Israel Hands uses distinctive terms and patterns more frequently than Long John Silver; The Pirate Round's Henry Nagel speaks more piratically than his pretentious boss Elephiant Yancy. And just as a stockbroker might speak differently with important clients at a meeting than with colleagues at a sports bar, oftentimes the same pirate speaks more piratically with certain people (Treasure Island's Long John Silver with Israel Hands, Winds of Chance's Japhet Bly with his messmates) than with others for whom he might consider standard English more appropriate (Long John Silver with Captain Smollett, Japhet Bly with Ursula Revell).

The term language also suggests a communal way of speaking. Frenchmen say oui to communicate with their compatriots because French is their common, official language. One might observe that pirates, on the other hand, often say things not because they are members of the pirate community, but because they are seamen (fair winds and following seas) or eighteenth-century Englishmen (alack now) or for any number of other reasons. The reality, however, is that, beyond (and sometimes even within) a very basic vocabulary of core terms, every language contains elements mirroring the non-ethnic, non-geographic identities of its speakers their other affiliations, interests, beliefs, pursuits. French doctors and lawyers, for example, communicate in sub-vocabularies better attributable to their professions than to any shared geography or ancestry. And, conversely, the pirate language includes a certain core vocabulary of terms spoken by pirates