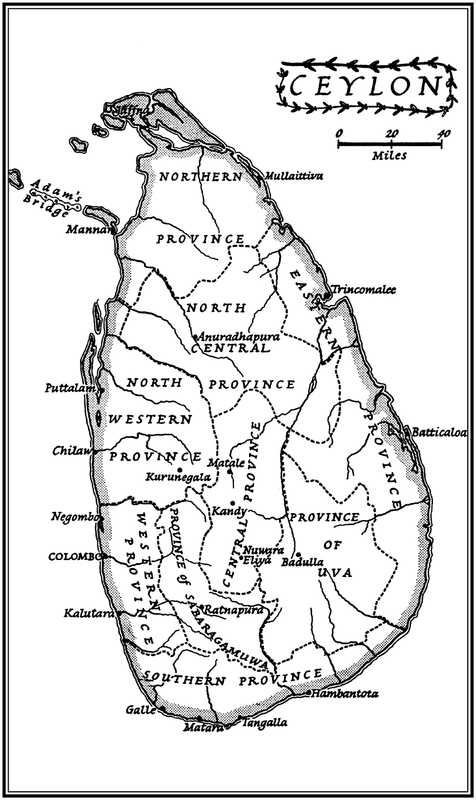

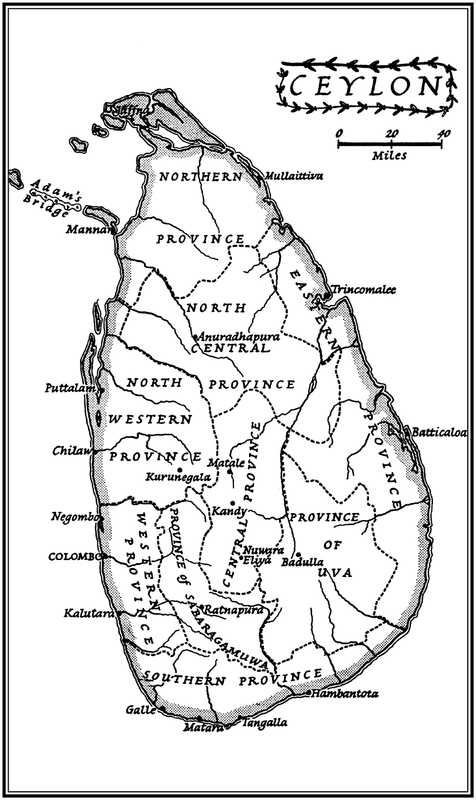

I have tried in the following pages to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, but of course I have not succeeded. I do not think that I have anywhere deliberately manipulated or distorted the truth into untruth, but I am sure that one sometimes does this unconsciously. In autobiography or at any rate in my autobiography distortion of truth comes frequently from the difficulty of remembering accurately the sequence of events, the temporal perspective. I have several times been surprised and dismayed to find that a letter or diary proves that what I remember as happening in, say, 1908, really happened in 1910; and the significance of the event may be quite different if it happened in the one year and not in the other. I have occasionally invented fictitious names for the real people about whom I write; I have only done so where they are alive or may be alive or where I think that their exact identification might cause pain or annoyance to their friends or relations. I could not have remembered accurately in detail fifty per cent of the events recorded in the following pages if I had not been able to read the letters which I wrote to Lytton Strachey and the official diaries which I had to write daily from 1908 to 1911 when I was Assistant Government Agent in the Hambantota District. I have to thank James Strachey for allowing me to read the original letters. As regards the diaries, I am greatly indebted to the Ceylon Government, particularly to the Governor, Sir Oliver Goonetilleke, and to Mr Shelton C. Fernando of the Ceylon Civil Service, Secretary to the Ministry of Home Affairs. When I visited Ceylon in 1960, Mr Fernando, on behalf of the Ceylon Government, presented me with a copy of these diaries and the Governor subsequently gave orders that they should be printed and published.

I n October 1904, I sailed from Tilbury Docks in the P&O Syria for Ceylon. I was a Cadet in the Ceylon Civil Service. To make a complete break with ones former life is a strange, frightening and exhilarating experience. It has upon one, I think, the effect of a second birth. When one emerges from ones mothers womb one leaves a life of dim security for a world of violent difficulties and dangers. Few, if any, people ever entirely recover from the trauma of being born, and we spend a lifetime unsuccessfully trying to heal the wound, to protect ourselves against the hostility of things and men. But because at birth consciousness is dim and it takes a long time for us to become aware of our environment, we do not feel a sudden break, and adjustment is slow, lasting indeed a lifetime. I can remember the precise moment of my second birth. The umbilical cord by which I had been attached to my family, to St Pauls, to Cambridge and Trinity was cut when, leaning over the ships taffrail, I watched through the dirty, dripping murk and fog of the river my mother and sister waving goodbye and felt the ship begin slowly to move down the Thames to the sea.

To be born again in this way at the age of twenty-four is a strange experience that imprints a permanent mark upon ones character and ones attitude to life. I was leaving in England everyone and everything I knew; I was going to a place and life in which I really had not the faintest idea of how I should live and what I should be doing. All that I was taking with me from the old life as a contribution to the new and to prepare me for my task of helping to rule the British Empire was ninety large, beautifully printed volumes of Voltaire the oily dark waters of the river through cold clammy mist and rain; the next day in the Channel it was barely possible to distinguish the cold and gloomy sky from the cold and gloomy sea. Within the boat there was the uncomfortable atmosphere of suspicion and reserve that is at first invariably the result when a number of English men and women, strangers to one another, find that they have to live together for a time in a train, a ship, a hotel.

In those days it took, if I remember rightly, three weeks to sail from London to Colombo. By the time we reached Ceylon, we had developed from a fortuitous concourse of isolated human atoms into a complex community with an elaborate system of castes and classes. The initial suspicion and reserve had soon given place to intimate friendships, intrigues, affairs, passionate loves and hates. I learned a great deal from my three weeks on board the P&O Syria. Nearly all my fellow-passengers were quite unlike the people whom I had known at home or at Cambridge. On the face of it and of them they were very ordinary persons with whom in my previous life I would have felt that I had little in common except perhaps mutual contempt. I learned two valuable lessons: first how to get on with ordinary persons, and second that there are practically no ordinary persons that beneath the faade of John Smith and Jane Brown there is a strange character and often a passionate individual.

One of the most interesting and unexpected exhibits was Captain L. of the Manchester Regiment, who, with a wife and small daughter, was going out to India. When I first saw and spoke to him, in the arrogant ignorance of youth and Cambridge, I thought he was inevitably the dumb and dummy figure that I imagined to be characteristic of any captain in the Regular Army. Nothing could have been more mistaken. He and his wife and child were in the cabin next to mine, and I became painfully aware that the small girl wetted her bed and that Captain L. and his wife thought that the right way to cure her was to beat her. I had not at that time read A Child is Being Beaten or any other of the works of Sigmund Freud, but the hysterical shrieks and sobs that came from the next cabin convinced me that beating was not the right way to cure bedwetting, and my experience with dogs and other animals had taught me that corporal punishment is never a good instrument of education.

Late one night I was sitting in the smoking-room talking to Captain L. and we seemed suddenly to cross the barrier between formality and intimacy. I took my life in my hands and boldly told him that he was wrong to beat his daughter. We sat arguing about this until the lights went out, and the next morning, to my astonishment, he came up to me and told me that I had convinced him and that he would never beat his daughter again. One curious result was that Mrs L. was enraged with me for interfering and pursued me with bitter hostility until we finally parted for ever at Colombo.

After this episode I saw a great deal of the captain. I found him to be a man of some intelligence and of intense intellectual curiosity, but in his family, his school and his regiment the speculative mind or conversation was unknown, unthinkable. He was surprised and delighted to find someone who would talk about anything and everything, including God, sceptically. We found a third companion with similar tastes in the Chief Engineer, a dour Scot, who used to join us late at night in the smoking-room with two candles so that we could go on talking and drinking whisky and soda after the lights had gone out. The captain had another characteristic, shared by me: he had a passion for every kind of game. During the day we played the usual deck games, chess, draughts, and even noughts and crosses, and very late at night when the two candles in the smoking-room began to gutter, he would say to me sometimes: And now, Woolf, before the candles go out, well play the oldest game in the world, the oldest game in the world, according to him, being a primitive form of draughts which certain arrangements of stones, in Greenland and African deserts, show was played all over the world by prehistoric man.