THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2014 by Robert Beachy

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House LLC, New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto, Penguin Random House companies.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Beachy, Robert.

Gay Berlin : birthplace of a modern identity / by Robert Beachy.

pages cm

ISBN 978-0-307-27210-2 (hardback) ISBN 978-0-385-35307-6 (ebook)

1. Gay menGermanyBerlinIdentity. 2. Gay cultureGermanyBerlin. 3. HomosexualityGermanyBerlin. 4. Gender identityGermanyBerlin. I. Title.

HQ76.2.G42B43 2014

306.7660943155dc23 2014004986

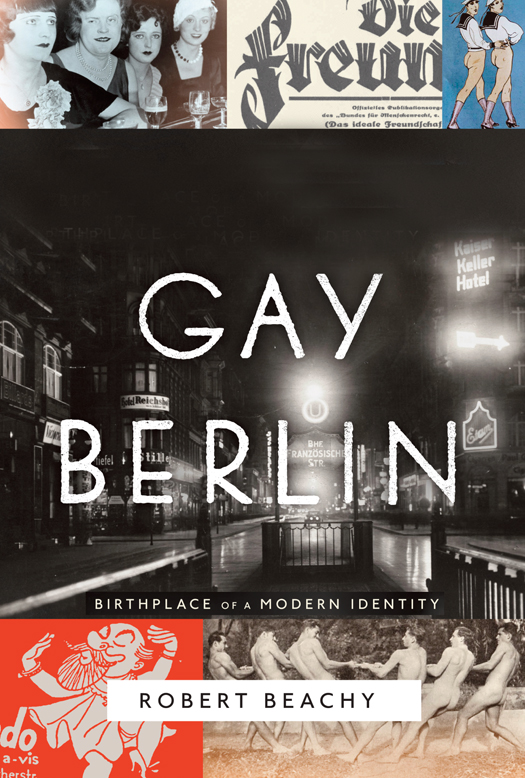

Jacket images: (top, left to right) transvestites, Eldorado nightclub, 1929, akg-images; Die Freundin, 1928; cabaret poster, Berlin, 1920; (middle) Berlin at night, 1928, akg-images; (bottom) Eldorado advertisement, c. 1920s; game of tug-of-war, anonymous photographer, 1930s

Jacket design by Evan Gaffney Design

v3.1

For Ada

(19252005)

Contents

Introduction

Look at me! blared the capital of the Reich. I am Babel, the monster among cities! We had a formidable army: now we command the most riotously wicked night life. Dont miss our matchless show, ladies and gentlemen! Its Sodom and Gomorrah in a Prussian tempo. Dont miss the circus of perversities! Our department store of assorted vices! An all-out tale of brand new kinds of debauchery!

KLAUS MANN , The Turning Point (1942)

I n October 1928,

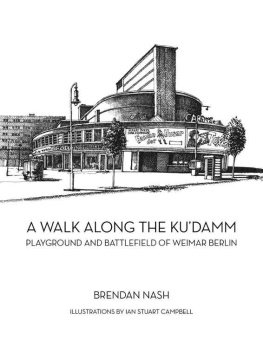

From the institute Auden and Isherwood went to eat in a restaurant just south of Unter den Linden, the main thoroughfare of Berlins historic center. After the meal, they made their way to Audens hangoutthe

Though few have left written traces as candid as Audens, there can be little doubt that Weimar Berlin was an astonishing revelation for many first-time visitors. After discovering the city for themselves, Auden and Isherwood became apostles for Berlins uninhibited sexuality, luring a wide circle of English authors, poets, and curiosity seekers. In his own autobiographical account, Isherwood described how Berlins openness freed him not only to explore his

Isherwoods recollection of this apparent coming out was composed decades after the fact, of course, and possibly romanticized his experience. But Audens Berlin journal offers immediate, contemporary evidence, showing clearly how Berlin shaped sexual identity. In a remarkable entry from April 6, 1929, the aspiring poet described a seemingly trivial event. Rushing to the train station to meet his current boyfriend, Gerhart, for an excursion to Hamburg, Auden had a brief encounter on the tram with a young woman. He describes how she made eye contact, approached him, and flirted: Shecame and stood beside me till I got out. I wanted to make an 18th century bow and say Entschuldigen Sie, Madam, aber ich bin schwul. The best translation of Audens imagined reply would be Excuse me, Madam, but I am gay. And what an incredible statement that would have been! Instead of disdain for his admirer, or bemusement, Auden believed her flirtation to be based on a misperception; she mistook Auden for a man who was attracted to women. And although Audens command of Germanby his own admissionwas never great, he formulated an appropriate response that his German admirer would have understood.

Audens use of this particular word, schwul, is especially striking. An

Emerging from Berlin vernacular, the term is the best translation for Audens Berlin awakening is striking, and in the late 1920s he could describe his sexuality more articulately even in halting German than he ever could in English.

The experiences that helped Auden to make this dramatic transition are significant, of course, but of equal interest are the contours of the terminology that evolved to describe the sexual minority to which he now felt he belonged. A central argument of Gay Berlin is that the emergence of an identity based on the notion of a fixed sexual orientation was initially a German and especially a Berlin phenomenon. This makes the Berlin etymology of schwul that much more significant, since language can help us to chart the growth of a new group identity.

The word schwul was neither the first nor the only German term, however, that shaped modern notions of sexual orientation. The word homosexuality was itself a German invention, and appeared as Homosexualitt for the first time in 1869 in a German-language pamphlet that polemicized against the Prussian anti-sodomy statute.

The claim of German originality does not deny, of course, that there have always been men and women who pursued erotic love with their own sex.

The

Other historians of sexuality have supported Foucaults periodization but questioned his exclusive emphasis on medicalization. In his study of Whether these late-nineteenth-century networks can be traced back to the molly houses, sodomites, or pederasts of the eighteenth century is theoretically debatable, but there are few demonstrable continuities.

Certainly the cosmopolitan culture and anonymity fostered by nineteenth-century European urbanization permitted the emergence of minority sexual communities. If we concede a qualitative shift, however, and not just numerical growth, we must also consider the kind of conceptual transformation addressed by Foucault. A centralif not the centralelement that has characterized modern homosexuality is the understanding of erotic same-sex attraction as a fundamental element of the individuals biological or psychological makeup. Homosexuality has thus been defined and constructed around the debate over the innate character of sexual identity, whether governed by nature or nurture, biology or culture, genetics or environment. The history of this debate, moreover, suggests that the idea of (homo)sexual personhood has a fairly recent origin.

This book will argue that the homosexual species took root in Germany after the mid-nineteenth century through the collaboration of Berlins medical scientists and sexual minorities. This confluence of biological determinism and subjective expressions of sexual personhood was a uniquely German phenomenon, moreover, and it clearly underpins modern conceptions of sexual orientation.

Foucault failed, however, to consider the German context of his own observations. Although he emphasized the word homosexuality and the work of the Berlin psychiatrist Carl Westphal, he never identified the urban context sources that gave rise to the neologism and its science as specifically German. Foucaults apparent oversight is even more glaring when we consider that homosexuality was only one in a series of German terms invented to describe erotic same-sex love as a fixed condition and social identity. Those who created this German-language terminology were advocates for legal reform, doctors who studied same-sex erotic behavior, and their subjects; all participated integrally in elaborating a science of homosexuality. The image Foucault has offered of a laboratory test tube in which medical professionals concocted new sexual identities is completely one-sided and misleading.