The Complete Works of

ADAM SMITH

(1723-1790)

Contents

Delphi Classics 2016

Version 1

The Complete Works of

ADAM SMITH

By Delphi Classics, 2016

COPYRIGHT

Complete Works of Adam Smith

First published in the United Kingdom in 2016 by Delphi Classics.

Delphi Classics, 2016.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form other than that in which it is published.

ISBN: 978 1 78656 046 9

Delphi Classics

is an imprint of

Delphi Publishing Ltd

Hastings, East Sussex

United Kingdom

Contact: sales@delphiclassics.com

www.delphiclassics.com

Parts Edition Now Available!

Love reading Adam Smith ?

Did you know you can now purchase the Delphi Classics Parts Edition of this author and enjoy all the novels, plays, non-fiction books and other works as individual eBooks? Now, you can select and read individual novels etc. and know precisely where you are in an eBook. You will also be able to manage space better on your eReading devices.

The Parts Edition is only available direct from the Delphi Classics website.

For more information about this exciting new format and to try free Parts Edition downloads , please visit this link .

The Books

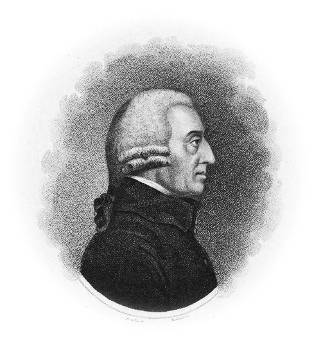

Kirkcaldy, a town and former royal burgh in Fife, on the east coast of Scotland Smiths birthplace

Portrait of Smiths mother, Margaret Douglas

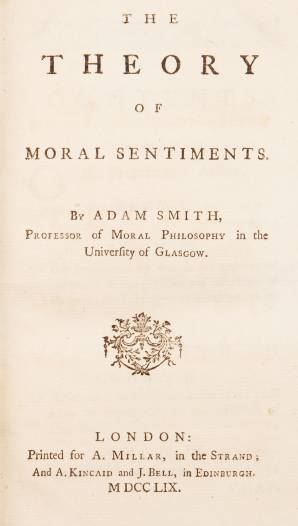

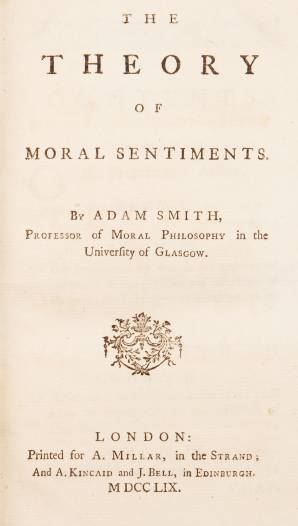

THE THEORY OF MORAL SENTIMENTS

First published in 1759, The Theory of Moral Sentiments provides the ethical, philosophical, psychological and methodological underpinnings to Adam Smiths later works. The ideas expressed in the text follow the views of his mentor, Francis Hutcheson of the University of Glasgow, who divided moral philosophy into four parts: Ethics and Virtue; Private rights and Natural liberty; Familial rights (Economics); and State and Individual rights (Politics). Hutcheson had abandoned the psychological view of moral philosophy, claiming that motives were too fickle to be used as a basis for a philosophical system. Instead, he hypothesised a dedicated sixth sense to explain morality. This idea, to be taken up by David Hume, claimed that man is pleased by utility.

In the work, Smith critically examines the moral thinking of his time, and suggests that conscience arises from dynamic and interactive social relationships through which people seek mutual sympathy of sentiments. His goal in writing the book was to explain the source of mankind's ability to form moral judgement, given that people begin life with no moral sentiments at all. Smith proposes a theory of sympathy, in which the act of observing others and seeing the judgements they form of both others and oneself makes people aware of themselves and how others perceive their behaviour. The feedback we receive from perceiving (or imagining) others' judgements creates an incentive to achieve "mutual sympathy of sentiments" with them and leads people to develop habits, and then principles, of behaviour, which come to constitute ones conscience.

Starting in 1741, Smith set on the task of using Humes experimental method (appealing to human experience) to replace the specific moral sense with a pluralistic approach to morality based on a multitude of psychological motives. The Theory of Moral Sentiments begins with the following assertion: How selfish soever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortunes of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it, except the pleasure of seeing it. Of this kind is pity or compassion, the emotion we feel for the misery of others, when we either see it, or are made to conceive it in a very lively manner. That we often derive sorrow from the sorrows of others, is a matter of fact too obvious to require any instances to prove it; for this sentiment, like all the other original passions of human nature, is by no means confined to the virtuous or the humane, though they perhaps may feel it with the most exquisite sensibility. The greatest ruffian, the most hardened violator of the laws of society, is not altogether without it.

Smith departs from the moral sense tradition of Shaftesbury, Hutcheson, and Hume, as the principle of sympathy takes the place of that organ. Sympathy was the term Smith uses for the feeling of these moral sentiments. It was the feeling with the passions of others. It operated through a logic of mirroring, in which a spectator imaginatively reconstructed the experience of the person he watches. However, Smith rejects the idea that Man is capable of forming moral judgements beyond a limited sphere of activity, again centred on his own self-interest.

Though first published in 1759, Smith continued making extensive revisions to the book, up until his death. In spite of The Wealth of Nations being widely regarded as his most influential work, it is believed that Smith himself considered The Theory of Moral Sentiments to be a superior work.

Francis Hutcheson (1694-1746), the Ulster-Scots philosopher that became known as one of the founding fathers of the Scottish Enlightenment.

CONTENTS

The first editions title page

Part I: Of the Propriety of Action Consisting of Three Sections

Section I: Of the Sense of Propriety

Chap. I: Of Sympathy

How selfish soever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortune of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it except the pleasure of seeing it. Of this kind is pity or compassion, the emotion which we feel for the misery of others, when we either see it, or are made to conceive it in a very lively manner. That we often derive sorrow from the sorrow of others, is a matter of fact too obvious to require any instances to prove it; for this sentiment, like all the other original passions of human nature, is by no means confined to the virtuous and humane, though they perhaps may feel it with the most exquisite sensibility. The greatest ruffian, the most hardened violator of the laws of society, is not altogether without it.

Next page