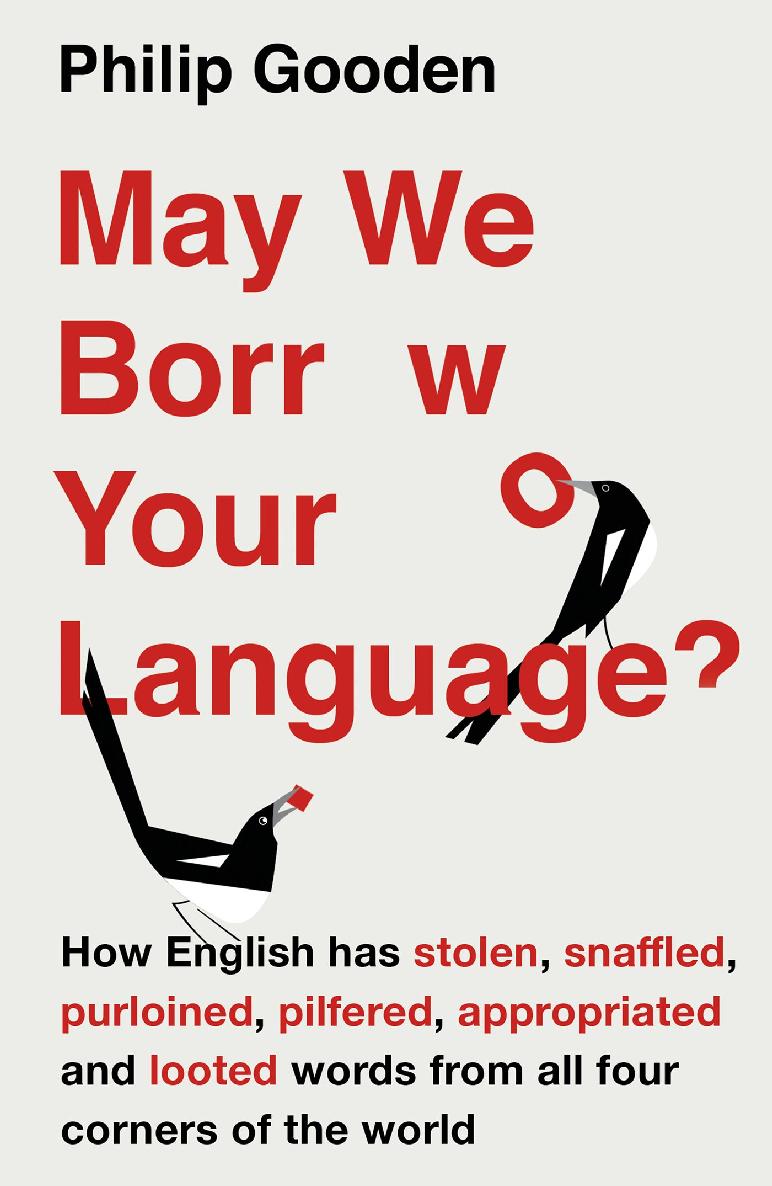

MAY WE BORROW YOUR LANGUAGE?

Philip Gooden

www.headofzeus.com

The English language that is spoken by one billion people around the world is a linguistic mongrel, its vocabulary a diverse mix resulting from centuries of borrowing from other tongues. From the Celtic languages of pre-Roman Britain to Norman French; from the Vikings Old Scandinavian to Persian, Arawak, Sanskrit, Cantonese, Hawaiian, Hebrew, Inuit and Urdu amongst a host of others we have enriched our modern language with such words as tulip, barbecue, nirvana, ketchup, ukulele, shibboleth, kayak and khaki.

May We Borrow Your Language? explores the intriguing and unfamiliar stories behind scores of familiar words that the English language has filched from abroad; in so doing, it also sheds fascinating light on the wider history of the development of the English we speak today.

Full of etymological nuggets to intrigue and delight the reader, this is a gift book for word buffs to cherish as cerebrally stimulating as it is more-ishly entertaining.

In memory of

F RANK M ILES

(19202013)

Contents

G OOD ARTISTS COPY ; GREAT artists steal, Picasso said, or is supposed to have said. English is a great language by any reckoning, and so it must also be reckoned as more of a thief than a copier. The title of this book is May We Borrow Your Language? and borrow is sometimes a euphemism for steal, as the subtitle indicates . Yet to steal words from another language does not deprive that language of its own words; rather it is to share the original expressions more widely, in the process often giving them a different spelling, another shape and perhaps a meaning that has strayed some distance from the one in the source. English is adept at this. The language is a great borrower, a practised thief.

In the same way that many books are made out of other books, almost all the words in English have been made out of words from other languages. History and geography provide the explanation. Britain, sitting semi-detached at the end of Europe and slightly above a line drawn midway across the continent, was from the first to the eleventh centuries AD the beneficiary of influences coming from both the north and south. These influences werent exactly a matter of choice for the occupants of the British Isles. Rather they were invasions, whether Roman, Anglo-Saxon, Viking or Norman; yet each wave of newcomers, instead of withdrawing after a period of occupation, was to remain and turn into settlers and then, over generations, into citizens.

At the same time as one ethnic layer was added to another, so one linguistic stratum was laid down on top of the previous one. And, as the boundaries between different ethnicities will grow more vague if no constraints are imposed on them, so too did the division between the different tongues used in England principally the division between Anglo-Saxon (Old English) and Norman French became increasingly uncertain, when one linguistic tradition seeped into another. A little might have been lost or discarded in the process, but much more was retained and added when words and expressions from different corners of Europe found themselves living in close quarters. All this makes the history of English a complicated business but it also explains something of the richness and density of the language.

The point about constraint, or rather the lack of it, is important, too. Unlike other linguistic cultures French springs to mind, for some reason English has always been open to foreign influence throughout its long history, whether the words and the ways of using them were brought across by soldiers or scholars, by merchants or migrants. The great period of British imperial expansion and consolidation, which began in the age of Elizabeth I and lasted until not so very long before the beginning of the reign of Elizabeth II, also saw a tremendous influx of terms from around the world, whether from India and all points east, or the Americas or Australasia. In the twentieth century, the cultural and military dominance of the United States not only guaranteed the status of English across the globe but the slightly different forms of the language used in America as opposed to Britain have themselves contributed to the store of words on both sides of the Atlantic.

May We Borrow Your Language? is a story of origins. By explaining where a selection of our English words comes from, it hints at the range, exoticism and idiosyncrasies of our language. The arrangement is chronological, beginning with terms from the seventh and eighth centuries, and travelling through a landscape that is at first Celtic, then Anglo-Saxon, then Norman, and then increasingly globalized in scope. I have chosen the words partly in a spirit of serendipity (see entry for the origin of this word, page ) and partly to give due weight to the contribution of each strand or stratum that makes up English as we use it today. The Anglo-Saxon or Old English one therefore outweighs the Viking or Norse one, while Celtic is inevitably reduced to some vestiges in place names and a few other topographical terms. Meanwhile Latin is everywhere in the period following the Conquest of 1066, not only because of the influence of that ancient language on the form of French spoken by the Normans but also because of its widespread use as the international language of scholarship and religious observance. And where there is Latin, Greek will not be far behind.

Sometimes, foreign languages have made a direct, untranslated contribution to English, and there is discussion in May We Borrow Your Language? of words like pasta , schadenfreude and agitprop , some of which seem to embody the culture that created them or so we might like to think. Then there are a handful of expressions that, very unusually, can be attributed to a particular person (gas, quark , meme ), one-off words that have come into existence by mistake (tranect, mondegreen ), and others whose origins are completely obscure, sometimes quite usual terms such as big , as well as eponymous expressions created out of peoples names ( Stalinist , Bowdlerize ) and portmanteau terms, slang and acronyms, and the occasional unclassifiable oddity like 24/7 .

This is not a methodical tread through the ages. The various centuries, from around the sixth or seventh to the twenty-first, are not evenly represented. Word creation goes in irregular waves, with a peak, for example, in the innovative and expansive Elizabethan and Jacobean periods. For contrast look at the difference between the first half of the twelfth century, for which fewer than 500 new words are cited in the Oxford English Dictionary ( OED ), and the almost 80,000 words cited in the first half of the seventeenth. Of course, many of these new dictionary words are offshoots of older ones as, for example, in the first recorded use of a noun in its verb form. But the general pattern is clear. Some eras and periods are worth more attention than others.

As a general note on featured words and phrases in May We Borrow Your Language?, words that are the subject of dedicated entries appear in bold (e.g. lexicographer ); those that are distinctively foreign or antiquated English are italicized (e.g. Weltschmerz from German or hyll from Old English); and those that are familiar in English but whose origins or use are being highlighted generally appear in quote marks (e.g. android and automaton in the robot section).