Sleight of Mouth

The Magic of

Conversational Belief

Change

by

Robert B. Dilts

Dilts Strategy Group

P.O. Box 67448

Scotts Valley, California 95067

Phone: +1 (831) 438-8314

E-Mail:

Homepage: http://www.diltsstrategygroup.com

Copyright 1999 by Robert Dilts and Dilts Strategy Group. Printed in the United States of America. All rights reserved. This book or parts thereof may not be reproduced in any form without written permission of the Publisher.

Library of Congress Card Number 99-07-44 02

I.S.B.N. 978-947629-02-8

I.S.B.N. 978-1947629-06-6 (e-book)

Contents

Dedication

This book is dedicated with affection and respect to:

Richard Bandler

John Grinder

Milton Erickson

and

Gregory Bateson

who taught me the magic of language

and the language of magic.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge:

Judith DeLozier, Todd Epstein, David Gordon, and Leslie Cameron-Bandler for their input and support at the time I was first evolving the ideas at the basis of Sleight of Mouth.

My children, Andrew and Julia, whose experiences and explanations helped me to understand the natural process of belief change and the meta structure of beliefs.

Ami Sattinger, who (as she has for so many other of my books and projects) helped with the proof reading and editing of this book.

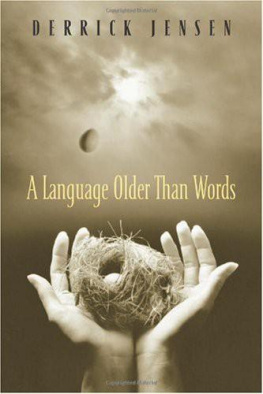

John Wundes who transformed some of the deeper structures underlying Sleight of Mouth into images, so that they could be seen more clearly. John created both the innovative cover picture and the wonderful drawings at the beginning of each chapter.

Preface

This is a book that I have been preparing to write for many years. It is a book about the magic of language, based on the principles and distinctions of Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP). I first came in contact with NLP nearly twenty-five years ago while attending a class on linguistics at the University of California at Santa Cruz. The class was being taught by NLP co-founder John Grinder. He and Richard Bandler had just finished the first volume of their groundbreaking work The Structure of Magic (1975). In this work, the two men modeled the language patterns and intuitive abilities of three of the worlds most effective psychotherapists (Fritz Perls, Virginia Satir and Milton Erickson). This set of patterns (known as the Meta Model ) allowed a person such as myself, a third year political science major, who had no personal experience with therapy of any type, to ask questions that an experienced therapist might ask.

I was struck by the possibilities of both the Meta Model and the process of modeling. It seemed to me that modeling had important implications in all areas of human endeavor: politics, the arts, management, science, teaching, and so on (see Modeling With NLP , Dilts, 1998). It struck me that the methodology of modeling could lead to broad innovations in many other fields involving human communication, reaching far beyond psychotherapy. As a student of political philosophy, my first modeling project was to apply the linguistic filters that Grinder and Bandler had used in their analysis of psychotherapists to see what patterns might emerge from studying the Socratic dialogs of Plato (Platos Use of the Dialectic in The Republic: A Linguistic Analysis , 1975; in Applications of NLP , Dilts, 1983).

While this study was both fascinating and revealing, I felt that there was more to Socrates persuasive abilities than the distinctions provided by the Meta Model could explain. The same was true for other verbal distinctions provided by NLP, such as representational system predicates (descriptive words indicating a particular sensory modality: see, look, hear, sound, feel, touch, etc.). These distinctions provided insight, but did not capture all of the dimensions of Socrates powers to persuade.

As I continued to study the writings and speeches of people who had shaped and influenced the course of human historypeople such as Jesus of Nazareth, Karl Marx, Abraham Lincoln, Albert Einstein, Mohandes Gandhi, Martin Luther King, and othersI became convinced that these individuals were using some common, fundamental set of patterns in order to influence the beliefs of those around them. Furthermore, the patterns encoded in their words were still influencing and shaping history, even though these individuals had been dead for many years. Sleight of Mouth patterns are my attempt to encode some of the key linguistic mechanisms that these individuals used to effectively persuade others and to influence social beliefs and belief systems.

It was an experience with NLP co-founder Richard Bandler that lead me to consciously recognize and formalize these patterns in 1980. In order to make a teaching point during a seminar, Bandler, who is renowned for his command of language, established a humorous but paranoid belief system, and challenged the group to persuade him to change it (see ). Despite their best efforts, the group members were unable to make the slightest progress in influencing the seemingly impenetrable belief system Bandler had established (a system based upon what I was later to label thought viruses).

It was in listening to the various verbal reframings that Bandler created spontaneously that I was able to recognize some of the structures he was using. Even though Bandler was applying these patterns negatively to make his point, I realized that these were the same structures used by people like Lincoln, Gandhi, Jesus, and others, to promote positive and powerful social change.

In essence, these Sleight of Mouth patterns are made up of verbal categories and distinctions by which key beliefs can be established, shifted or transformed through language. They can be characterized as verbal reframes which influence beliefs, and the mental maps from which beliefs have been formed. In the nearly twenty years since their formalization, the Sleight of Mouth patterns have proved to be one of the most powerful sets of distinctions provided by NLP for effective persuasion. Perhaps more than any other distinctions in NLP, these patterns provide a tool for conversational belief change.

There are challenges in teaching these patterns effectively, however, because they are about words, and words are fundamentally abstract. As NLP acknowledges, words are surface structures which attempt to represent or express deeper structures . In order to truly understand and creatively apply a particular language pattern, we must internalize its deeper structure. Otherwise, we are simply mimicking or parroting the examples we have been given. Thus, in learning and practicing Sleight of Mouth, it is important to distinguish genuine magic from trivial tricks. The magic of change comes from tapping into something that goes beyond the words themselves.

Until now, the Sleight of Mouth patterns have typically been taught by presenting learners with definitions and a number of verbal examples illustrating the various linguistic structures. Learners are left to intuitively figure out the deeper structure necessary to generate the patterns on their own. While, in some ways, this mirrors the way that we learned our own native language as children, it can also present certain limitations.

For instance, people (especially non-native speakers of English) have experienced the Sleight of Mouth patterns as powerful and useful, but at times they can be somewhat complex and confusing. Even Practitioners of NLP (including those with many years of experience) are not always clear about how these patterns fit together with other NLP distinctions.

Next page