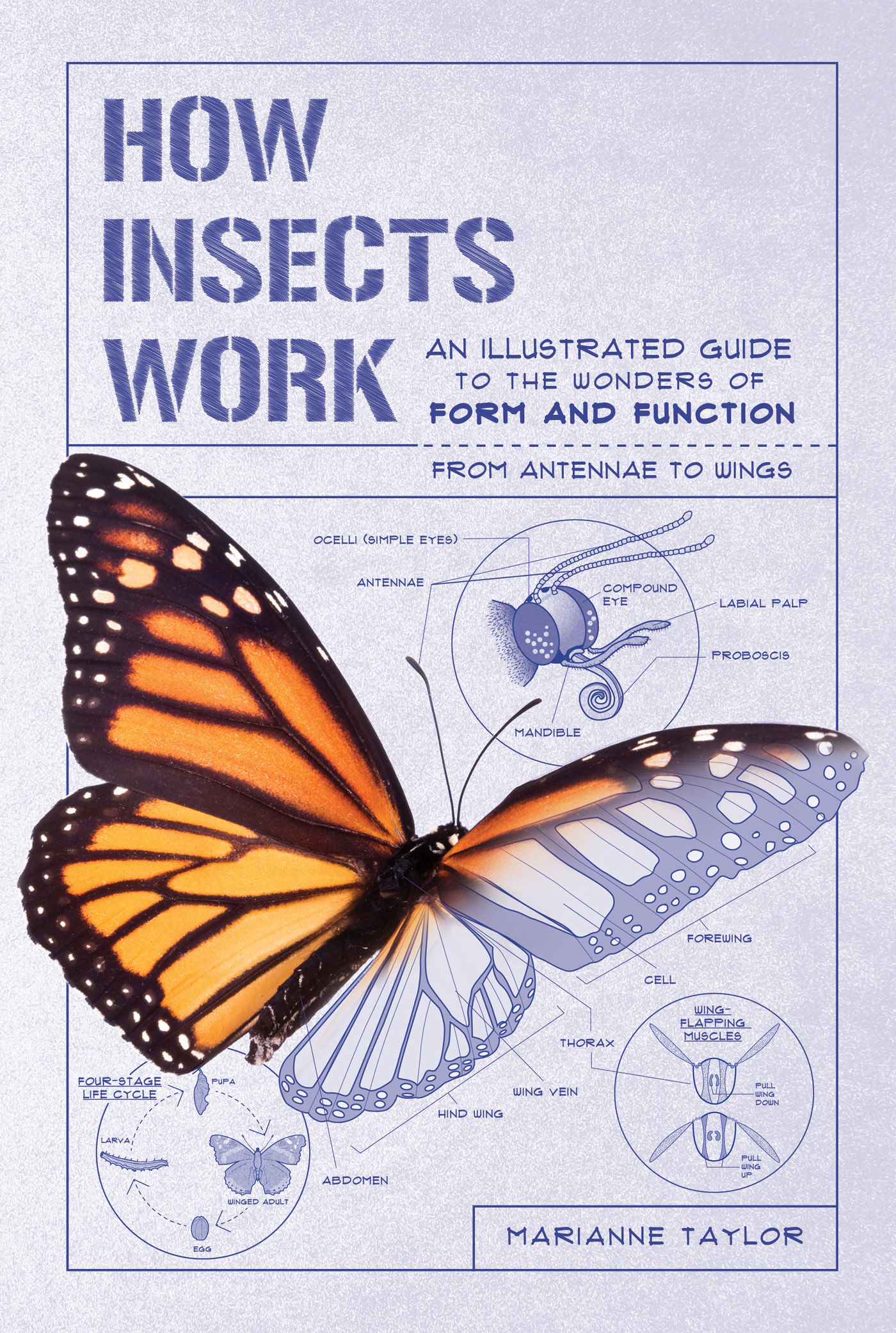

Marianne Taylor - How Insects Works

Here you can read online Marianne Taylor - How Insects Works full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: The Experiment, genre: Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:How Insects Works

- Author:

- Publisher:The Experiment

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

How Insects Works: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "How Insects Works" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

How Insects Works — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "How Insects Works" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Across the great and varied sweep of life on Earth, insects stand out as one of the greatest success stories. Most invertebrate animals live in the oceans and fresh waters, but insects have truly conquered the land, and (as the only winged invertebrates that have ever lived) they have also mastered the air. This mastery comes courtesy of a basic anatomy that meets the challenges of life out of water, and thanks also to countless anatomical modifications that allow insects to thrive in so many different habitats and ecological niches.

For all their fabulous variety, insects have the same fundamental body-plan, which allows them to be recognized at a glance. The segmented body has three distinct sections: the head, the thorax, and the abdomen. There are six legs and (usually) two pairs of wings attached to the thoracic segments, and there are obvious eyes and various sensory and feeding appendages on the head. Whether the insect crawls, runs, climbs, or hangs, whether it flies with a rattling zoom, a buzz, or a flutter, whether it hunts prey, chews leaves, or sucks nectar (or blood), it does so with its own version of the same physical equipment that first evolved more than 350 million years ago.

A spectacular Spiny Flower Mantis exhibits its eye-spot wing markings, to startle a predator.

One of the keys to insects success in the open air lies in their outer coveringa waxy cuticle that helps prevent their tiny bodies from dehydrating. To take oxygen from the air, they use spiraclesbreathing apertures in the body-segments, which take in air passively and can be opened and closed as needed. Instead of blood contained in vessels, they have free-flowing hemolymph, which helps keep their bodies rigid, aids movement, and assists the transportation of nutrients and waste materials to the appropriate parts of the body. The nervous system is modularin a sense, each of the body segments has its own individual and autonomous brainand some other body systems show a similar modularization. These are just a few of the many ways in which insect bodies are structured and function completely differently from our own, though it is the process of complete bodily metamorphosis, from wormlike larva to winged adult, that astounds us most of all.

The male Stag Beetle is a fighting machinehis huge jaws are for wrestling a rival rather than biting.

There are well over a million species of insects known to science today, and probably many more that are as yet undiscovered. They have adapted to live on every continent and in every kind of environment, fulfilling an array of ecological roles. Some are our constant companionsa few are even domesticated for our useand others are our sworn enemies, but the vast majority are almost unknown to most of us. This book aims to unravel the mystique of insectshow their bodies work, how they lead their lives, and how deeply and completely the lives of other organisms on Earth (including ourselves) depend on them.

The Madagascan Sunset Moth is noted for its long migrations as well as its dazzling colors.

Insects are the most successful and diverse of all land animals. Their long evolutionary history has furnished them with uniquely adaptable bodies, capable of thriving in all environments. They have survived five mass extinctions, and many species have even surmounted the greatest challenge of allsuccessfully surviving alongside humanity.

Trilobites were ancient arthropods and cousins to the insectstheir segmented structure has proved an enduringly successful body-plan.

Insects are invertebrate animals belonging to the larger group Arthropoda, meaning jointed feet. Their bodies also have movable joints at certain points on their rigid outer shell.

Humans, along with other mammals and all vertebrates, have an endoskeleton. The strong, rigid framework of bones is inside, with muscles, blood vessels, nerves, and other soft, fleshy structures around them. In insects, this anatomy is reversed. Their structural framework, the exoskeleton, is on the outside and the soft parts are within.

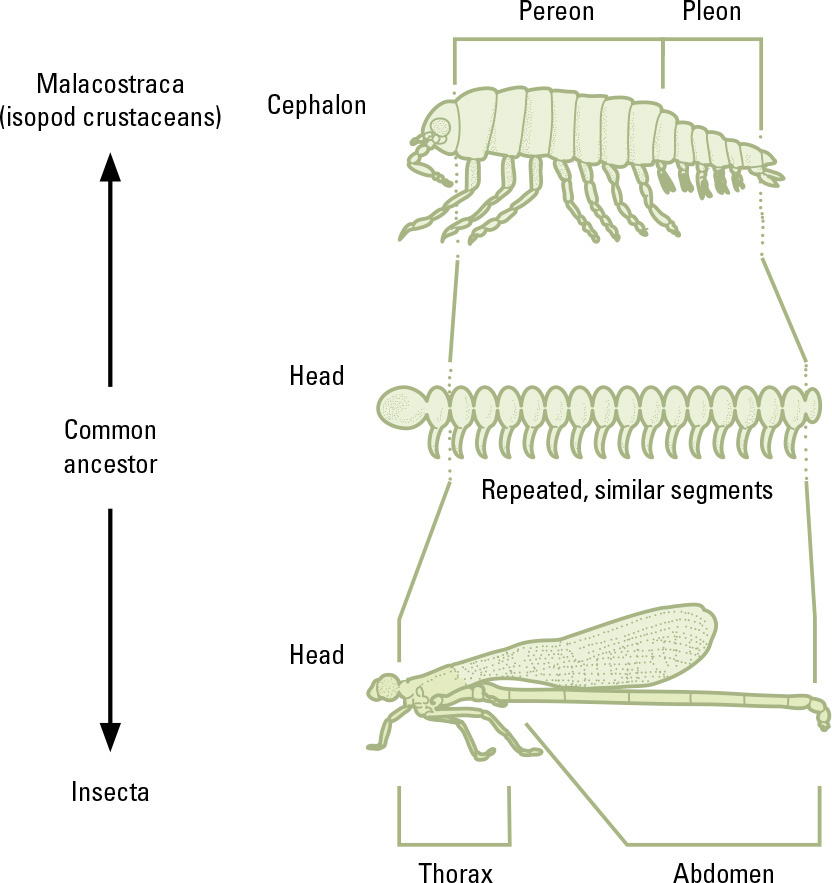

As well as insects, the arthropod group today includes crabs and other crustaceans, spiders and other arachnids, and the many-legged millipedes and centipedes. Their basic body-plan is bilateral symmetry, with left and right as mirror images, and the body is divided into many sections, called segments. The jointed legs and other limbs or appendages are in pairs along each side.

The first animal with a segmented exoskeleton and jointed limbs lived more than 540 million years ago, in the sea. Its appearance was a major event in evolution, introducing a very adaptable body arrangement. (An incidental benefit is that a strong, tough exoskeleton was much more likely to be preserved as a fossila huge help for our studies today.) The earliest fossil arthropods were small organisms, from the size of rice grains to grapes, and resembled a mix of worm and crustacean. But these remains are vague and difficult to classify.

Fossil trilobites: These early arthropods first appeared on Earth some 521 million years ago.

Modern arthropods like crustaceans (here an isopod) and insects (here a damselfly) both descend from an animal with simple repeated body-segments, each bearing jointed appendages.

Trilobites were swimming arthropods that lived in seas worldwide some 525 million years ago, during the Cambrian Period. The sea scorpions, or eurypterids, formed another prominent arthropod group. These fearsome predators first lived around 460 million years ago, in the Ordovician Period. Some, such as Jaekelopterus, were among the largest arthropods of all time, at 8 feet (2.5m) long. Both trilobites and eurypterids flourished for more than 200 million years, then gradually declined. The last of them died out in the PermianTriassic mass extinction event, 252 million years ago.

Meanwhile, other arthropods had moved onto land, probably 430 to 450 million years ago during the Ordovician Period. Their basic body design and anatomy were already well suited to terrestrial lifea feature in evolutionary science known as preadaptation. The tough, impermeable exoskeleton greatly reduced body fluid loss in air, and the jointed limbs held up the body for moving around. Some of the first terrestrial arthropods were trigonotarbids, which were arachnids similar to their modern spider relatives. Mostly small, to inch (0.5 to 2cm) in length, they went extinct about 290 to 300 million years ago. A very different destiny awaited one of the next arthropod groups to colonize landthe insects.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «How Insects Works»

Look at similar books to How Insects Works. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book How Insects Works and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.