Introduction

THE LIFE OF PAPER

ascesis

involved in writing

my history

ive been waking in

night sweats &

its not the sheets,

those things in

side are

burning out

of love

17 JUNE 2009

WRITING AND REWRITING THIS BOOK has been a slow burnas the case may be now for you, too, kindly reading it. On the one hand, to myself and to those who have shared their stories with me (and probably also to others still holding their stories close to themselves), the central argument of this study is obvious, almost too obvious to necessitate book-length explanation: this is, simply, that letters can mean the world to the people attached to them, and distinctively so for communities ripped apart by incarceration. In the first and final instance, this is a formulation of the life of paper that you must accept at face value in its plenitude, a plenitude that is all but better represented by understatement than long-winded analysis. If one does not accept this, chances are that no amount of research could effect otherwise because the problem would not have been a matter of fact, even if it becomes so profoundly one of logic.

Yet, on the other hand, I have nevertheless felt compelled to corroborate the existence of such a phenomenon, plain as it may be. And once I committed to doing so by giving it name, the self-evidence of all meaning seemed to vanish. And so, each and every time I come to the page, my own creativity always begins at a loss.

Part of the problem I experience with narrating this life of paper is, indeed, an effect of my object of study, the letter itself; in turn, my issues become productive of the very means through which I problematize the letter for the sake of study, too. Assumptions of both the transparency and the significance of the letter have long captured civic imagination, as conveyed by H.T. Loomis in the introduction to his textbook, Practical Letter Writing (1897): Ones habits and abilities are judged by his letters,and usually correctly.... The qualifications necessary to enable a person to write a good business or social letter are a fair English education, ready command of language, and

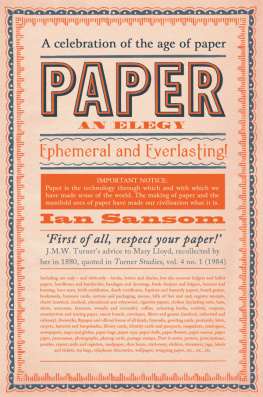

By the time of his books publication at the close of the nineteenth century, Loomis was already lamenting the assumed obsolescence of the handwritten letter, casualty in the sweeping momentum of technological advance wherein these busy days, the old-fashioned letter is replaced by brief notes, telegrams, or telephonic messages. Rendered defunct by the progress of human genius and invention, apparently the epistolary would have no place in ages to come. Yet, if he begins by announcing the letters extinction, then why write the bookand moreover, why characterize its activity as practical? For Loomis, the ultimate function of this education in the neatness, correct forms, and established customs in writing letters seems to reside less in the use-value or objectivity of the letter as commodity than in the object the letter itself produces: Western civilization as suchits embodiment in and through correct and incorrect positions (figure 1), acquisition of proper habits, abilities, intelligence, and business tact, achievement of general mastery over the affairs of life.

FIGURE 1. H. T. Loomis, Practical Letter Writing (Cleveland, OH: Practical Textbook Co., 1897), 6. Original caption reads, Correct and Incorrect positions.

If the epistolary thus mediates mans becoming at this most essential scale of economy, then my own questions become: what is a letter, what does it do and how does it work, on the other side of human masterythought and learned, written and read, sent and received from an other side of history? What vitalizes human relationships to the letter when the human embodies the crisis rather than cultivation of man and the mortal stakes of the problem of representation? In three parts, The Life of Paper hence deals with these questions at the interstices of aesthetic, racial, geographic, and ontological form: exploring the lifeworlds maintained through letter correspondence in particular contexts of racism and mass incarceration in California history. Tracing the contradictions of modernity that inhere in as well as mobilize around the letter itself, its mediation of social struggles to define Western civilization as well as its reinvention of ways of life that the latter cannot subsume, this investigation unfolds in three cycles to uncover how letters facilitate a form of communal life for groups targeted for racialized confinement in different phases of development in California, this distinctive or iconic part of the U.S. West.

Part 1, Detained, focuses on migrants from southern China during the peak years of U.S. Chinese Exclusion (1890s1920s). These chapters elaborate the distinct pathways that detained communities forgedin and through lettersto rearticulate emergent infrastructures defining an epoch of global imperialist expansion, capitalist industrialization, and nation-state formation predicated on exclusions understood in terms of racial distinction. Part 2, Interned, focuses on families of Japanese ancestry during the World War II period (1930s1940s) and examines processes of aesthetic production in interned communities through letters, in dialectic with global developments in systems of censorship and surveillance. Part 3, Imprisoned, focuses on socialities of Blackness in the postCivil Rights era (1960spresent), interrogating how the Black radical tradition has vitalized practices of reembodying the human as imprisoned communities of different ethnoracial heritage engage letter correspondence to survive collectively through dramatic restructurings of global capitalism, U.S. apartheid, and racial order that all bond societies in California and beyond to prisons as anchoring institutions of civic life.