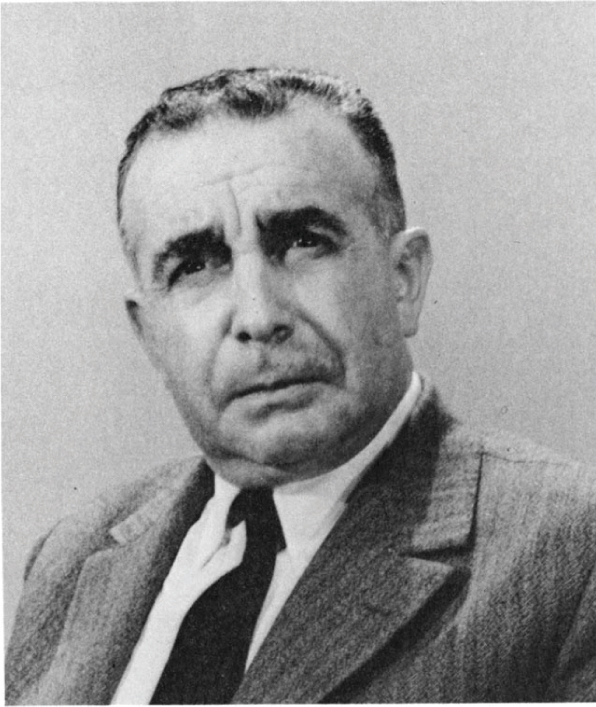

Everyone knows that in France there are few logicians but many historians of science; and that in the philosophical establishment whether teaching or research oriented they have occupied a considerable position. But do we know precisely the importance that, in the course of these past fifteen or twenty years, up to the very frontiers of the establishment, a work like that of Georges Canguilhem can have had for those very people who were separated from, or challenged, the establishment? Yes, I know, there have been noisier theatres: psychoanalysis, Marxism, linguistics, ethnology. But let us not forget this fact which depends, as you will, on the sociology of French intellectual environments, the functioning of our university institutions or our system of cultural values: in all the political or scientific discussions of these strange sixty years past, the role of the philosophers I simply mean those who had received their university training in philosophy departments has been important: perhaps too important for the liking of certain people. And, directly or indirectly, all or almost all these philosophers have had to come to terms with the teaching and books of Georges Canguilhem.

From this, a paradox: this man, whose work is austere, intentionally and carefully limited to a particular domain in the history of science, which in any case does not pass for a spectacular discipline, has somehow found himself present in discussions where he himself took care never to figure. But take away Canguilhem and you will no longer understand much about Althusser, Althusserism and a whole series of discussions which have taken place among French Marxists; you will no longer grasp what is specific to sociologists such as Bourdieu, Castel, Passerson and what marks them so strongly within sociology; you will miss an entire aspect of the theoretical work done by psychoanalysts, particularly by the followers of Lacan. Further, in the entire discussion of ideas which preceded or followed the movement of 68, it is easy to find the place of those who, from near or from afar, had been trained by Canguilhem.

Without ignoring the cleavages which, during these last years after the end of the war, were able to oppose Marxists and non-Marxists, Freudians and non-Freudians, specialists in a single discipline and philosophers, academics and non-academics, theorists and politicians, it does seem to me that one could find another dividing line which cuts through all these oppositions. It is the line that separates a philosophy of experience, of sense, and of subject and a philosophy of knowledge, of rationality and of concept. On the one hand, one network is that of Sartre and Merleau-Ponty; and then another is that of Cavaills, Bachelard and Canguilhem. In other words we are dealing with two modalities according to which phenomenology was taken up in France, when quite late around 1930 it finally began to be, if not known, at least recognized. Contemporary philosophy in France began in those years. The lectures on transcendental phenomenology delivered in 1929 by Husserl (translated by Gabrielle Peiffer and Emmanuel Levinas as Mditations cartsiennes ,Paris, Colin, 1931; and by Dorion Cairns as Cartesian Meditations , The Hague, Nijhoff, 1960) marked the moment: phenomenology entered France through that text. But it allowed of two readings: one, in the direction of a philosophy of the subject and this was Sartres article on the Transcendance de lEgo (1935) and another which went back to the founding principles of Husserls thought: those of formalism and intuitionism, those of the theory of science, and in 1938 Cavaills two theses on the axiomatic method and the formation of set theory. Whatever they may have been after shifts, ramifications, interactions, even rapprochements, these two forms of thought in France have constituted two philosophical directions which have remained profoundly heterogeneous.

On the surface the second of these has remained at once the most theoretical, the most bent on speculative tasks, and also the most academic. And yet it was this form which played the most important role in the sixties, when a crisis began, a crisis concerning not only the University but also the status and role of knowledge. We must ask ourselves why such a mode of reflection, following its own logic, could turn out to be so profoundly tied to the present.

Undoubtedly one of the principal reasons stems from this: the history of science avails itself of one of the themes which was introduced almost surreptitiously into late eighteenth century philosophy: for the first time rational thought was put in question not only as to its nature, its foundation, its powers and its rights, but also as to its history and its geography; as to its immediate past and its present reality; as to its time and its place. This is the question which Mendelssohn and then Kant tried to answer in 1784 in the Berlinische Monatschrift :Was ist Aufklrung? (What is Enlightenment?), These two texts inaugurated a philosophical journalism which, along with university teaching, was one of the major forms of the institutional implantation of philosophy in the nineteenth century (and we know how fertile it sometimes was, as in the 1840s in Germany). They also opened philosophy up to a whole historico-critical dimension. And this work always involves two objectives which in fact cannot be dissociated and which incessantly echo one another: on the one hand, to look for what was the moment (in its chronology, its constituent elements, its historical conditions) when the West first asserted the autonomy and sovereignty of its own rationality: the Lutheran Reformation, the Copernican Revolution, Cartesian philosophy, the Galilean mathematization of nature, Newtonian physics? On the other hand, to analyze the present moment and, in terms of what was the history of this reason as well as of what can be its present balance, to look for that relation which must be established with this founding act: rediscovery, taking up a forgotten direction, completion or rupture, return to an earlier moment, etc.

Undoubtedly we should ask why this question of the Enlightenment, without ever disappearing, had such a different destiny in Germany, France and the Anglo-Saxon countries; why here and there it was invested in such different domains and according to such varied chronologies. Let us say in any case that German philosophy gave it substance above all in a historical and political reflection on society (with one privileged moment: the Reformation; and a central problem: religious experience in its relation with the economy and the state); from the Hegelians to the Frankfort School and to Lukcs, Feuerbach, Marx, Nietzsche and Max Weber it bears witness to this. In France it is the history of science which has above all served to support the philosophical question of the Enlightenment; after all, the positivism of Comte and his successors was one way of once again taking up the questioning by Mendelssohn and Kant on the scale of a general history of societies. Knowledge belief; the scientific form of knowledge and the religious contents of representation; or the transition from the pre-scientific or scientific; the constitution of a rational way of knowing on the basis of traditional experience; the appearance, in the midst of a history of ideas and beliefs, of a type of history suitable to scientific knowledge; the origin and threshold of rationality it is under this form, through positivism (and those opposed to it), through Duhem, Poincar, the noisy debates on scientism and the academic discussions about medieval science, that the question of the Enlightenment was brought into France. And if phenomenology, after quite a long period when it was kept at the border, finally penetrated in its turn, it was undoubtedly the day when Husserl, in the Cartesian Meditations and the Crisis ( The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology ,translated by David Carr, Evanston, Ill., Northwestern University Press, 1970) posed the question of the relations between the Western project of a universal development of reason, the positivity of the sciences and the radicality of philosophy.