The stories in this book are true. A few names have been changed to protect the privacy of people involved.

Copyright 2020 by Rachel Vorona Cote

A previous version of Nerve appeared in Literary Hub, October 27, 2016.

Previous versions of Close appeared in Jezebel, April 21, 2015, and September 23, 2015. Close also includes excerpts from Painted Ladies, an essay first published online by The Poetry Foundation.

A previous version of Cut appeared in Broadly (now Vice), March 15, 2017.

A previous version of Old appeared in Literary Hub, January 5, 2017.

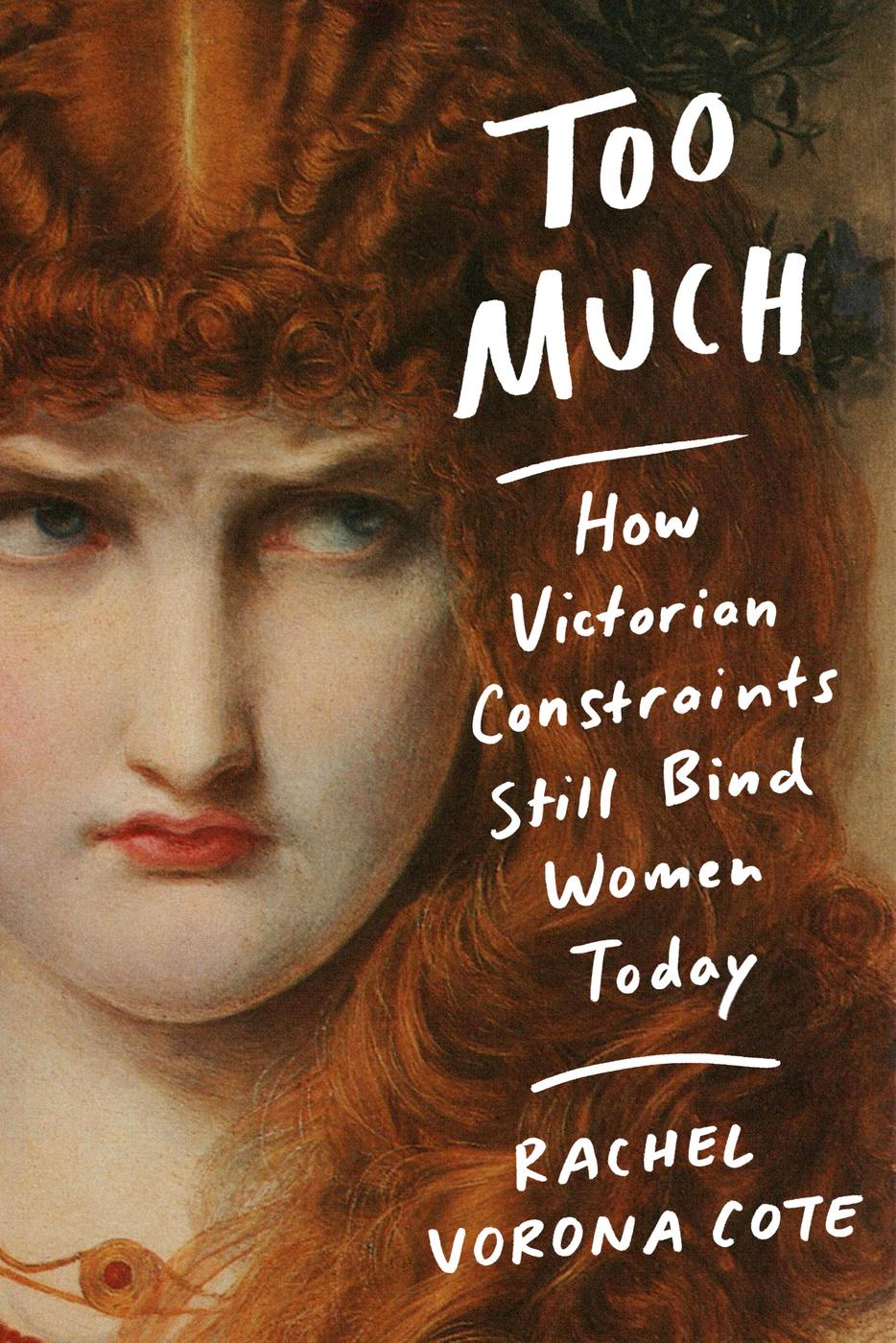

Cover design by Jenny Carrow. Painting: Helen of Troy by Anthony Frederick Sandys/Alamy. Cover copyright 2020 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Grand Central Publishing

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

grandcentralpublishing.com

twitter.com/grandcentralpub

First Edition: February 2020

Grand Central Publishing is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Grand Central Publishing name and logo is a trademark of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Cote, Rachel Vorona, author.

Title: Too much : how Victorian constraints still bind women today / Rachel

Vorona Cote.

Description: First edition. | New York : Grand Central Publishing, [2020]

Identifiers: LCCN 2019036413 | ISBN 9781538729700 (trade paperback) | ISBN 9781538729717 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Women--Identity. | Sex role--History. | Excess (Philosophy)

| Feminism. | Women--Social conditions--19th century. | Women and

literature--History--19th century.

Classification: LCC HQ1206 .C7223 2020 | DDC 305.42--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019036413

ISBNs: 978-1-5387-2970-0 (trade paperback), 978-1-5387-2971-7 (ebook)

E3-20200225-DA-PC-CCC

E3-20200124-DA-PC-ORI

For my mother, Katherine Florio Vorona, whose compassionate heart and boundless empathy taught me that no amount of love is too much. If she had not raised me, and embraced everything I amwith all my excess, unruliness, and contradictionsI could not have written this book.

Explore book giveaways, sneak peeks, deals, and more.

Tap here to learn more.

B efore venturing any further, its important that I address a few matters related to diversity in source material. Victorian literature is a useful tool for exploring the phenomenon of too muchness, but like so many mechanisms for critical thought, it is limited, racially and otherwise. Throughout the book, I will reference and draw principally from Victorian narratives and conduct manuals. However, I will also place them alongside others in order to, I hope, provide a broader purview beyond that of the cisgender white woman. That said, I will, for the sake of (relative) brevity, primarily focus on woman-identifying persons over the course of the book, although there remains much work to be done in considering the emotional circumscription of transgender persons, gender nonconforming persons, and men, queer and straight. This is a long and intricate conversation: I submit the following book as one rivulet leading to vaster waters.

Finally, I want to turn this narrative of too muchness on its head without letting empathy out of sightthis isnt an excuse to do and say whatever we want, context and consideration be damned. It is, however, a call for others to witness a broad, more complex range of emotional presentation and utterance, and a demand for the space we cohabit to be treated as capacious ground for any expression that is neither malicious nor harmful to folk, flora, and fauna. I believe that this is possible. In writing this book, I am declaring my belief that it will exist, that we are, gradually, making it so.

Wonderland:

An Introduction

A weeping woman is a monster. So too is a fat woman, a horny woman, a woman shrieking with laughter. Women who are one or more of these things have heard, or perhaps simply intuited, that we are repugnantly excessive, that we have taken illicit liberties to feel or fuck or eat with abandon. After bellowing like a barn animal in orgasm, hoovering a plate of mashed potatoes, or spraying out spit in the heat of expostulation, weve flinched in self-scornugh, that was so gross. I am so gross. On rare occasions, we might revel in our excessbelting out anthems with our friends over karaoke, perhapsbut in the company of less sympathetic souls, our uncertainty always returns. A woman who meets the world with intensity is a woman who endures lashes of shame and disapproval, from within as well as without.

In Victorian England, the medical establishment would have labeled us hysterical, pathologically immoderate in emotional and physiological expression. Heres how a German-born doctor practicing in London, one Julius Althaus, defined the condition in 1866: All the symptoms of hysteria have their prototype in those vital actions by which grief, terror, disappointment, and other painful emotions and affections, are manifested under ordinary circumstances, and which become signs of hysteria as soon as they attain a certain degree of intensity. Of course, a certain degree of intensity invites a vast range of interpretation, and when it came to emotional eruptions, the Victorians were none too generous. Hysteria was a convenient means of pathologizingand thus regulatingfeminine feeling and its expression. Today, as many among us grieve our political optimism and hammer out our anger on social media, we find our husbands, our boyfriends, our parents, our politicians diagnosing us with similar maladies: were wallowing in it, why are we so freaked out, we must be bleeding out of our wherever. Take a Xanax, girl, and calm down.

We are the women who can hardly contain our screams, and, oftentimes, we dont. Our muchness oozes from our pores like acidic sweat: ranker, more caustic, less concealable than ever. But however brutally the stigma may sizzle in this political moment, this sense that we are somehow Too Much is hardly new to usnor will it dissipate whenever Donald Trumps vise finally unclenches from our skulls. I conceived the idea for this booka critical cry of bullshit against this concept, Too Muchsome years ago, during a comparatively happier presidency. This term, Too Much, pernicious in its ambiguity, attacks with the force of history. Its the overdetermined exponent of ideologies, centuries old, structured by misogyny, racism, and homophobia. American society fetishizes white heteronormative propriety: it wants its girls pliable and demuregirls who safeguard both tears and sex for the privacy of the bedroom, who keep their voices measured during meetings, and who brush their hair and blot their lipstick. It worships the woman who, if she should experience distress, will wear her sadness like Lana Del Rey or