Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

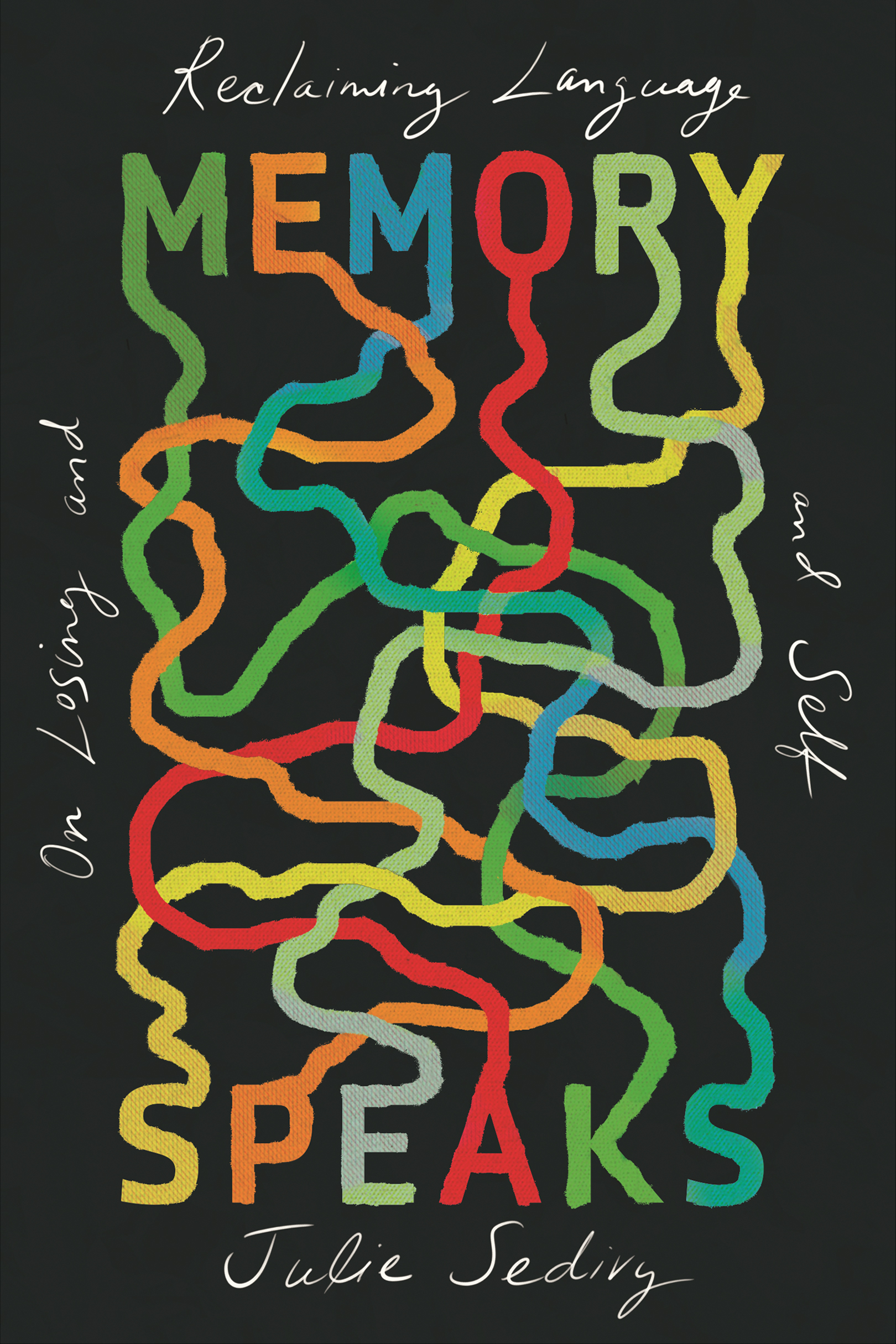

MEMORY SPEAKS

On Losing and Reclaiming Language and Self

Julie Sedivy

THE BELKNAP PRESS OF HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2021

Copyright 2021 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

All rights reserved

Jacket design by Jaya Miceli

978-0-674-98028-0 (cloth)

978-0-674-26964-4 (EPUB)

978-0-674-26963-7 (PDF)

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Sedivy, Julie, author.

Title: Memory speaks : on losing and reclaiming language and self/Julie Sedivy.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021007518

Subjects: LCSH: Language attrition. | Second language acquisition. | Language revival. | Language and languagesPolitical aspects. | Psycholinguistics.

Classification: LCC P40.5.L28 S435 2021 | DDC 401/.93dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021007518

To Vera and Ladislav, and those who came before.

To Katharine and Benjamin, and those who will come after.

Contents

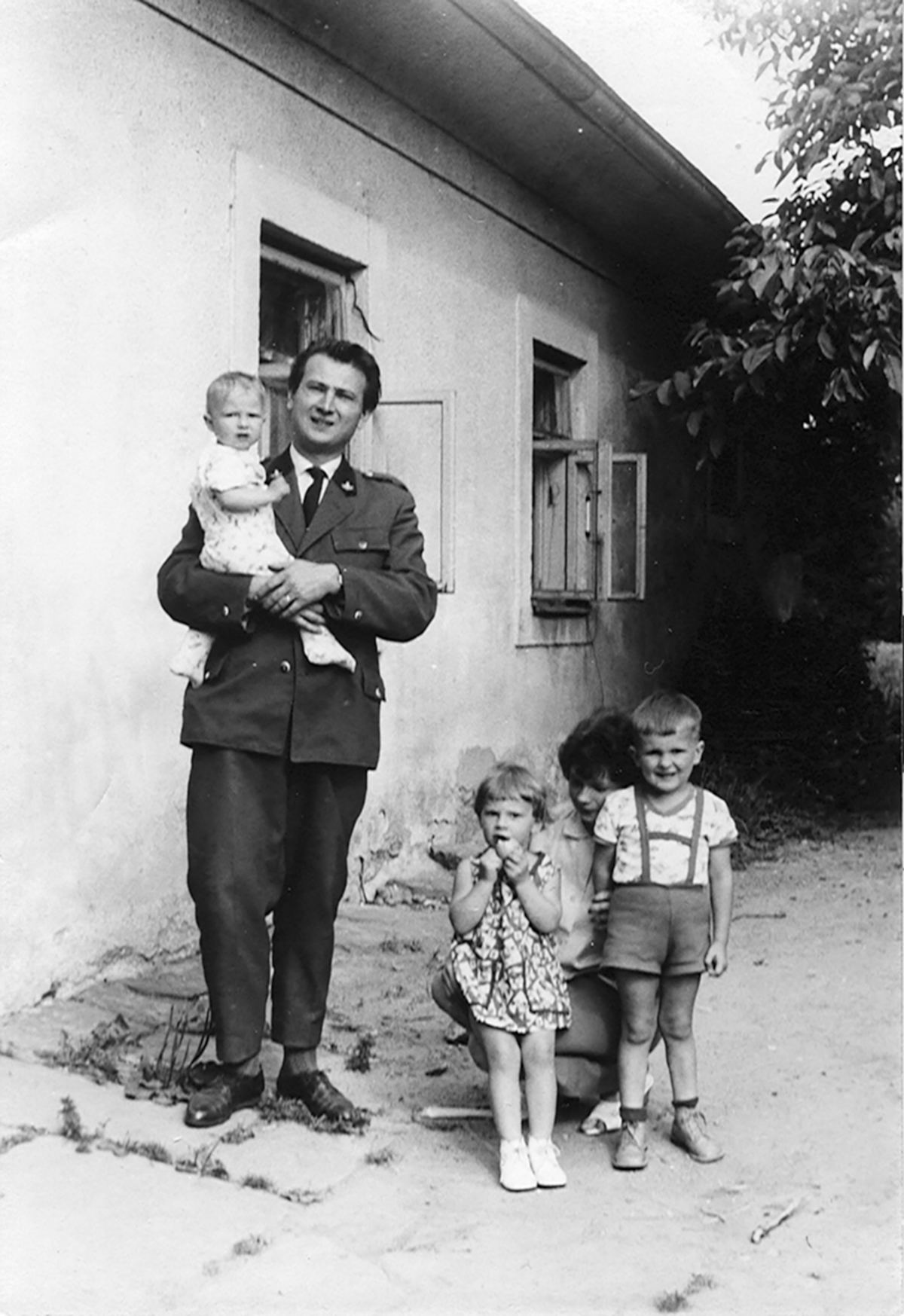

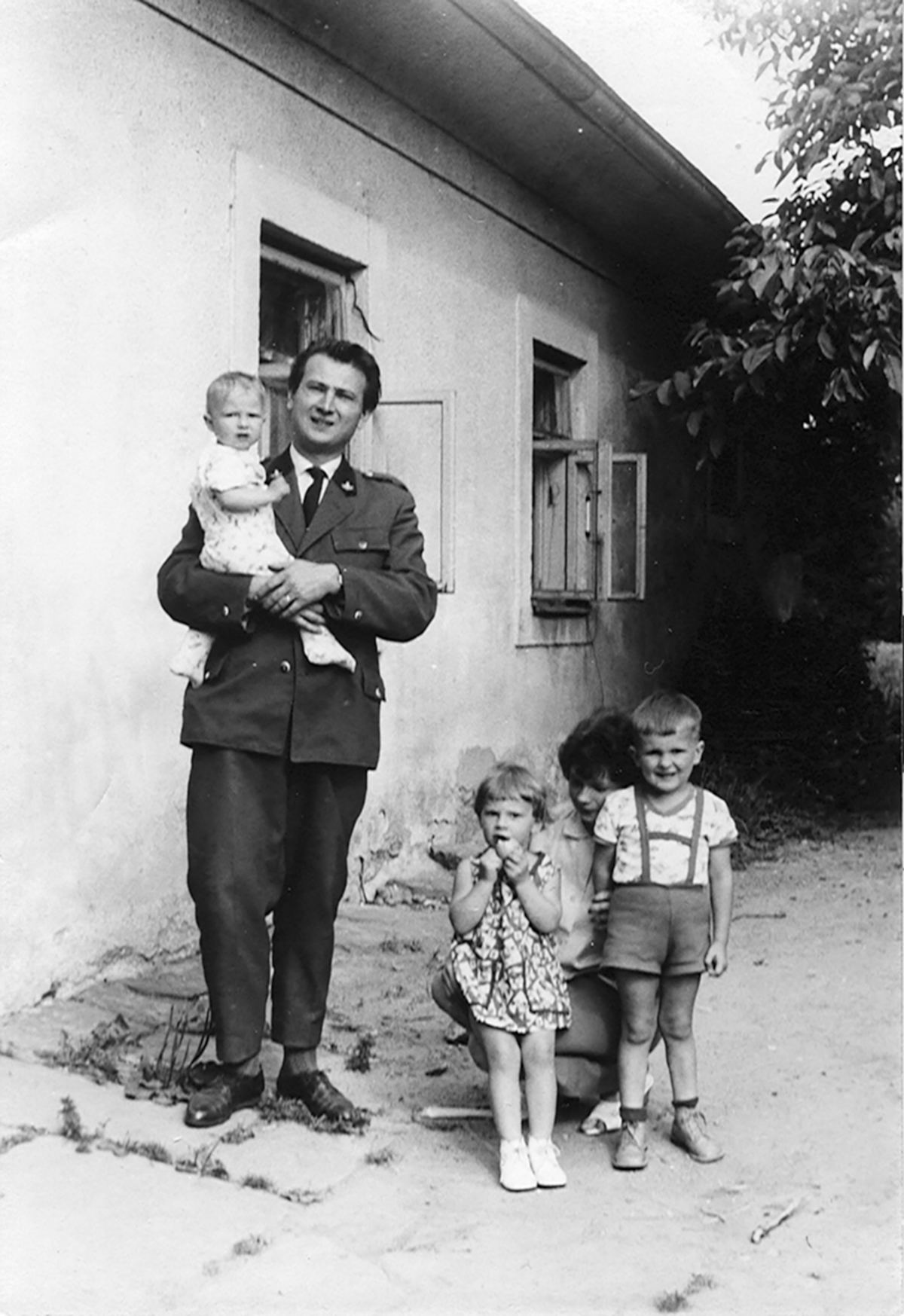

Nestled in my fathers arms, I pose with my family in front of our home a few months before our departure from Czechoslovakia.

My father died as he had done most things throughout his life: without preparation and without consulting anyone. He simply went to bed one night and was found the next morning lying amid the sheets like his own stone monument.

It was hard for me not to take my fathers abrupt exit as a rebuke. For years, hed been begging me to visit him in the Czech Republic, where Id been born and where hed gone back to live in 1992. Each year, I delayed. I was in that part of my life when the marriage-grad-school-children-career-divorce current was sweeping me along with breath-sucking force, and a leisurely trip to the fatherland seemed as plausible as pausing the flow of time.

Now my dad was shrugging at me from beyondYou see, youve run out of time.

His death underscored another, subtler loss: that of my native tongue. Czech was the only language I knew until the age of two, when my family began a migration westward, from what was then Czechoslovakia through Austria, then Italy, settling eventually in Montreal, Canada. Along the way, a clutter of languages introduced themselves into my life: German in preschool, Italian-speaking friends, the Francophone streets of East Montreal. Linguistic experience congealed, though, once my five siblings and I started school in English. As with many immigrants, this marked the moment when English became, unofficially and over the grumbling of my parentsespecially my fatherour family language. What could my parents do? They were outnumbered. Czech began its slow retreat from our daily life.

I entered kindergarten knowing only a few words of English. Upon ascending to first grade, I was mortally offended when my teacher, taking inventory of the immigrant kids in her class on the first day of school, asked me, What about you, Julie? Do you know a little English? Indignant, I announced (in what Im sure was still a thick Slavic accent), I dont know a little EnglishI know a lot of English. A few years later, no teacher could distinguish my speech from that of my native-born peers. Today, people who know me are startled to learn that English was the fifth language I learned to speak, so thoroughly has it elbowed its predecessors aside.

Many would applaud the efficiency with which our family settled into Englishits what exemplary immigrants do. And to me at that time, the price of assimilation was invisible. Like most young people, I was far more intent on hurtling myself into my future than on tending my ancestral rootsand that future, it was clear, was an English-speaking one. In my world, Czech was a small language, spoken only on our tiny domestic island by people genetically related to me. English was the big, horizon-hungry language, the language of the teachers I adored or had to appease, the language of the TV shows my friends endlessly rehashed, of the books that held me in thrall and the books I thought I might one day write. It was the language of dreams and goals.

But there was a price. As my siblings and I distanced ourselves from the Czech language, a space widened between us and our parentsespecially my father, whose English sat on him like a poorly tailored suit. It was as if my parents life in their home country, and the values that defined that life, didnt translate credibly into another language; it was much easier to rebel against them in English. Even the English names for our parents encouraged dissent: The tender Czech words wed usedMaminka, Tatinekare impossible to pronounce with contempt, but they have no corresponding forms. In English, the sweet but childish Mommy and Daddy are soon abandoned for Mom and Dadwords that, we discovered, lend themselves perfectly well to adolescent snark.

Ive wondered, recently, whether things might have been different for my father had his children remained rooted in their native tongue. Over time, we spoke together less and less. I remember watching him grow frustrated at his powerlessness to pass on to his children the legacies he most longed to leave: an ardent religiosity, the nurturing of family ties, pleasure in the music and traditions of his region (which, Im now ashamed to say, we often mocked), and a tender respect for ancestors. All of these became diluted by the steady flow of our new experiences narrated in English, laced with Anglophone aspiration and individualism. As we entered adulthood and dispersed all over North America into our self-reliant lives, my father gave up. He moved back home.

For the next two decades, I lived my adult life, fully absorbed into the English-speaking universe, even adding American citizenship to my Canadian one. My dad was the only person with whom I regularly spoke Czechif phone calls every few months could be described as regularly, and if my clumsy sentences patched together with abundant English could be called speaking Czech. My Czech heritage began to feel more and more like a vestigial organ.

But loss inevitably clarifies that which is gone. When my father died, and with him, my connection to Czech, it was as if the viola section in the orchestra had fallen silentnot carrying the melody, it had gone unnoticed, but its absence announced how much depth and texture it had supplied, how its rhythms had lent coherence to the music. In grieving my father, I became aware of how much I also mourned the silencing of Czech in my life. There was a part of me, I realized, that only Czech could speak to, a way of being that was hard to settle into, even with my own siblings and mother when we spoke in English. I suddenly felt unmoored, not only from my childhood, but from the entire culture that had shaped me.

I have been thinking about that loss ever since, becoming intimate with its outline and its various shadings. And I have been thinking about language my whole life, often all day and every day since I first wandered into a linguistics class as a fresh university student. In my subsequent work as a researcher in psycholinguistics, a field that is preoccupied with the psychological aspects of language, I have puzzled through the minute details of how we learn and use language. But little about my studies prepared me for the inexplicable void I felt in connection with a language I rarely spoke anymore.