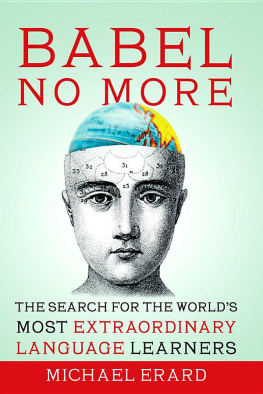

W e all learn at least one language as children. But what does it take to learn six languages, twenty... seventy? Such feats of linguistic prowess provide a glimpse into what the human brain is capable ofand hold up a mirror to our desire to live without language barriers on a shrinking planet.

In Babel No More , Michael Erard, a monolingual with benefits, sets out on a quest to meet language superlearners and make sense of their mental powers. On the way he uncovers the secrets of historical figures like the nineteenth-century Italian cardinal Giuseppe Mezzofanti, who was said to speak seventy-two languages and was such a legend that when he died people all over Europe vied for his skull. Emil Krebs, a pugnacious fin de sicle German diplomat, spoke sixty-eight languages, and Erard sees the evidence of this in Krebss dissected brain. Lomb Kat, a Hungarian hyperpolyglot who taught herself Russian by reading Russian romance novels, believed that one learns grammar from language, not language from grammar. These massive multilinguals have long offered a natural experiment into the limits of the brain; here, at last, we can inspect the results.

On his way to tracking down the one man who could be called the most linguistically talented person in the world, Erard meets other living language-superlearners. Among them is Alexander, a modern-day polyglot with dozens of languages who shows him the tricks of the trade and gives him a dark glimpse into the life of obsessive language acquisition. I came to consider him as a holy man, writes Erard. Others do yoga; Alexander does grammatical exercises.

With his ambitious examination of what language is, where it lives in the brain, and the cultural implications of polyglots pursuits, Erard explores the upper limits of our ability to learn and to use languages, and illuminates the intellectual potential in everyone. How do some people escape the curse of Babeland what might the gods have demanded of them in return?

MICHAEL ERARD has graduate degrees in linguistics and rhetoric from the University of Texas at Austin. He has written about language, linguists, and linguistics for Science, Slate, Wired, The Atlantic, The New York Times, New Scientist, and many other publications, and is a contributing writer for Design Observer . He is the author of one other book, Um... : Slips, Stumbles, and Verbal Blunders, and What They Mean . Michael was awarded the Dobie Paisano Writing Fellowship in 2008 to work on Babel No More .

MEET THE AUTHORS, WATCH VIDEOS AND MORE AT

SimonandSchuster.com

THE SOURCE FOR READING GROUPS

JACKET DESIGN ZCALO DESIGN

JACKET IMAGES: HEAD ALCHEMY/ALAMY;

GLOBE GETTY IMAGES

COPY RIGHT 2012 SIMON & SCHUSTER

Thank you for purchasing this Free Press eBook.

Sign up for our newsletter and receive special offers, access to bonus content, and info on the latest new releases and other great eBooks from Free Press and Simon & Schuster.

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

ALSO BY MICHAEL ERARD

Um... : Slips, Stumbles, and Verbal Blunders, and What They Mean

Free Press

A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2012 by Michael Erard

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Free Press Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Free Press hardcover edition January 2012

FREE PRESS and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Erard, Michael.

Babel no more : the search for the worlds most extraordinary language learners / Michael Erard.1st Free Press hardcover ed.

p. cm.

1. Historical linguistics. I. Title.

P140.E73 2012

401.93dc23 2011027964

ISBN 978-1-4516-2825-8 (print)

ISBN 978-1-4516-2827-2 (eBook)

For Misty

Contents

Part 1

QUESTION: Into the Cardinals Labyrinth

Part 2

APPROACH: Tracking Down Hyperpolyglots

Part 3

REVELATION: The Brain Whispers

Part 4

ELABORATION: The Brains of Babel

Part 5

ARRIVAL: The Hyperpolyglot of Flanders

Catch a young swallow.

Roast her in honey.

Eat her up.

Then you will understand all languages.

Folk magic incantation

When we wonder, we do not yet know

if we love or hate the object at which

we are marveling; we do not yet know

if we should embrace it or flee from it.

Stephen Greenblatt,

Marvelous Possessions

Babel No More

Part 1

QUESTION:

Into the Cardinals Labyrinth

Introduction

T o sea-going travelers of 1803, pirates in the Mediterranean posed a terrifyingly reliable threat. So when an Italian priest, Felix Caronni, set out from the Sicilian port of Palermo, it was conceivable that neither he nor the ships cargo of oranges would ever see their destination. Indeed, Caronnis boat was captured, and for a year he was jailed on the northern coast of Africa, headed for certain slavery, until French diplomats secured his release.

When the priest returned to Italy, he set out to write an account of his narrow escape. Appearing in 1806, it was the first published mention of a certain professor of Oriental languages at the University of Bologna who had helped Caronni translate a document from Arabic. This twenty-nine-year-old professor, Giuseppe Mezzofanti, a priest and the son of a local Bolognese carpenter, was reputed to know twenty-four languages.

More than thirty years later, a group of English tourists visiting Rome sought out Mezzofanti and asked him how many languages he spoke. By then he was the Vatican librarian and would soon be elevated to cardinal. I have heard many different accounts, one tourist asked the prelate, but will you tell me yourself?

Mezzofanti hesitated. Well, if you must know, I speak forty-five languages.

Forty-five! the tourist exclaimed. How, sir, have you possibly contrived to acquire so many?

I cannot explain it, said Mezzofanti. Of course God has given me this peculiar power: but if you wish to know how I preserve these languages, I can only say, that, when once I hear the meaning of a word in any language, I never forget it.

Engraving of Giuseppe Mezzofanti.

At other times, when asked how many languages he spoke, Mezzofanti liked to quip that he knew fifty languages and Bolognese. During his lifetime, he put enough of those fifty on displayamong them Arabic and Hebrew (biblical and Rabbinic), Chaldean, Coptic, Persian, Turkish, Albanian, Maltese, certainly Latin and Bolognese, but also Spanish, Portuguese, French, German, Dutch, and English, as well as Polish, Hungarian, Chinese, Syrian, Amharic, Hindustani, Gujarati, Basque, and Romanianthat he frequently appeared in rapturous accounts of visitors to Bologna and Rome. Some compared him to Mithridates, the ancient Persian king who could speak the language of each of the twenty-two territories he governed. The poet Lord Byron, who once lost a multilingual cursing contest with Mezzofanti, called him a monster of languages, the Briareus of parts of speech, a walking polyglott, and more,who ought to have existed at the time of the Tower of Babel, as universal interpreter. Newspapers described him as the distinguished linguist, the most learned linguist now living, the most accomplished linguist ever seen, the greatest linguist of modern Europe. He was continually referred to as the pinnacle of human achievement with languages. A British civil servant who directed a survey of all the languages of India between 1894 and 1928 summed up the linguistic situation in the province of Assam, where eighty-one languages were spoken, by writing that Mezzofanti himself, who spoke fifty-eight languages, would have been puzzled here.

Next page