Contents

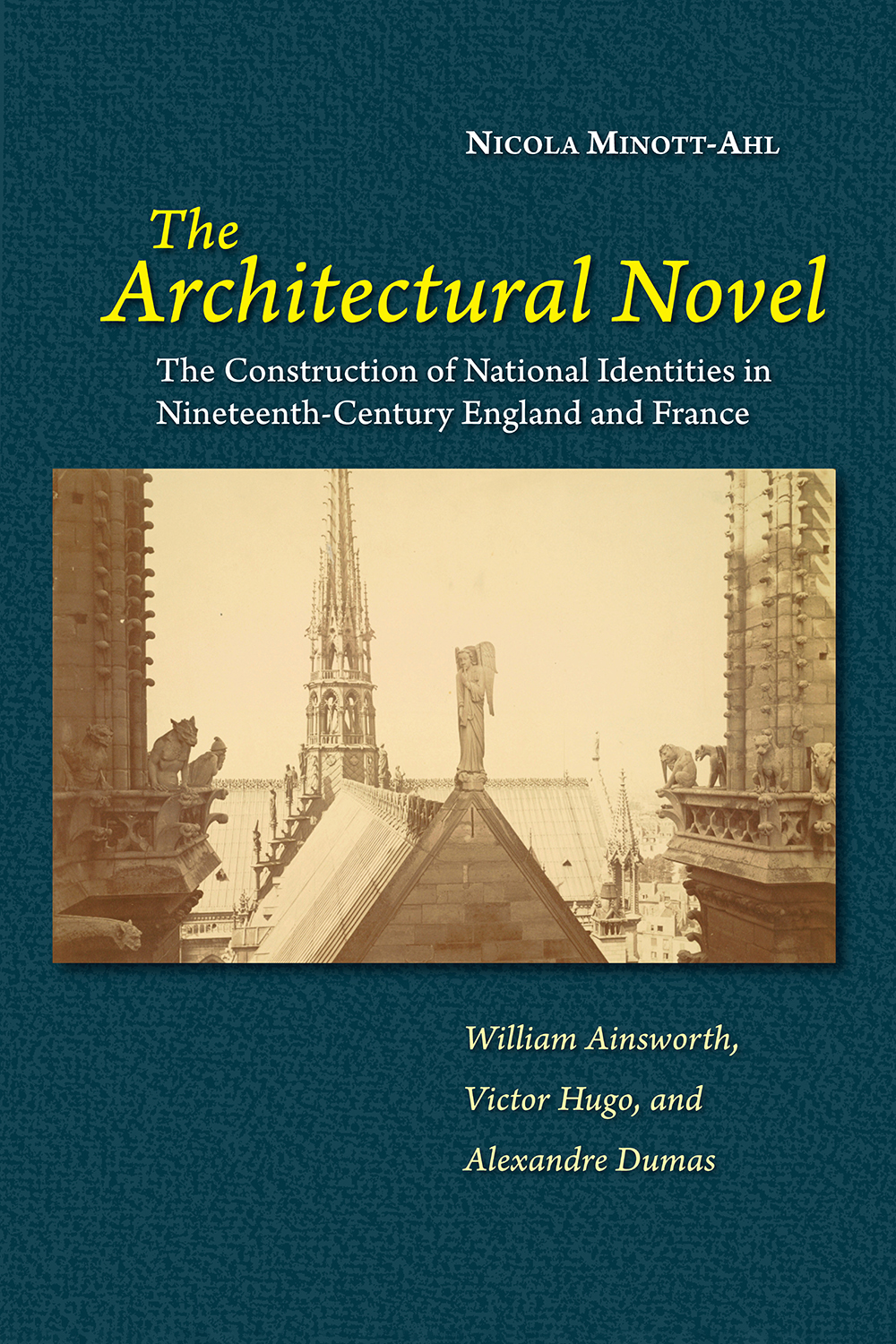

The

Architectural Novel

The

Architectural Novel

The Construction of National Identities in

Nineteenth-Century England and France

N ICOLA M INOTT-AHL

Copyright Nicola Minott-Ahl, 2022.

Published in the Sussex Academic e-Library, 2021.

SUSSEX ACADEMIC PRESS

PO Box 139, Eastbourne BN24 9BP, UK

Ebook editions distributed worldwide by

Independent Publishers Group (IPG)

814 N. Franklin Street

Chicago, IL 60610, USA

ISBN 9781789761481 (Paperback)

ISBN 9781782847526 (Epub)

ISBN 9781782847526 (Kindle)

ISBN 9781782847526 (Pdf)

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This e-book text has been prepared for electronic viewing. Some features, including tables and figures, might not display as in the print version, due to electronic conversion limitations and/or copyright strictures.

Contents

Acknowledgments

This book lets me explore how three of my favorite nineteenth-century novelists transform architectural structures that occupy a single physical space but were constructed over extended time into portable narratives, self-narrating realities, intertextures of philosophy, religion, politics, history and historiography, all within the context of literary fiction. I am fascinated by how they empower diverse fields of artistic and intellectual inquiry to interact with and influence one another without destroying the characteristics that define their works as novels. Since my approach is not invested in a sub-specialty within an already carefully delimited field, I found it hard, at first, to see how such a wide-ranging project could yield a sustained and integrated work (like a book). But, along the way, I have been helped by sublime moments of professional engagement with scholars doing similar work. Our dynamic exchanges regarding method, approach, and conclusions in our disparate fields have been valuable opportunities to interact with other minds and traverse the broad scope of literature in every genre and medium.

My thanks go first to my teacher, mentor, dissertation adviser, and friend, Felicia Bonaparte, Professor Emerita of English at CUNY Graduate Center and The City College of New York, who understood the syncretic nature of my dissertation and subsequent research. To the other members of my dissertation committee, William Coleman, Professor Emeritus of English and Comparative Literature and Donald Stone, late, great Emeritus Professor of English at Queens College and CUNY Graduate School, I also offer heartfelt thanks for their encouragement and unwavering belief in my ultimate academic success. Then, I thank Pieter Vermeulen and Ortwin de Graef who organized and invited me to the 2009 conference Matters of State: Bildung and Literary-Intellectual Discourse in the Nineteenth Century in Leuven, Belgium. This conference led to my involvement in forming the Literary London Society. I always returned to my work from its sessions bubbling with enthusiasm and fresh ideas. My first article appeared in the Literary London Journal, which continued to provide opportunities for refining and testing ideas underpinning this book. My thanks, then, to Brycchan Carey and my Literary London colleagues for supporting my scholarship and consistently assembling international scholars from every literary field to write and talk about London in literature and to David Skilton , FRSA FEA and Emeritus Professor at the School of English, Communication and Philosophy at Cardiff University another devotee of Literary London conferences, whose professional and intellectual generosity enriched my life in so many ways.

I also thank Linda Robertson, Professor of Media and Society at Hobart and William Smith Colleges, whose friendship, personal and intellectual, has sustained me unwaveringly. She has taught me much about teaching and scholarship, has read many drafts, and pushed me to publish this book, as did James-Henry Holland, Associate Professor of Asian Studies at Hobart and William Smith Colleges, whose friendship, endless curiosity, and interest led me both to further insights and to ensuring those insights are accessible to non-specialists. George Joseph, Professor Emeritus of French and Francophone Studies at Hobart and William Smith Colleges and Thelma Pinto, Director Emerita of Africana Studies at Hobart and William Smith Colleges have my eternal love and gratitude for their friendship and professional guidance.

I must also acknowledge and thank: my husband, Frederick Ahl, Professor of Classics and Comparative Literature at Cornell University, for unflinching support, willingness to read the many versions of my manuscript, and for help with the nuances of Jehan Frollos Greek; John Ahl and Martin Ahl, our sons and my most compelling reasons never to give up, who believe I can do anything; Clayton and Lucia Minott, my parents, who have been with me every step of the way, unceasingly encouraging and supportive, models of generosity, and of moral and spiritual strength; my sister Natalie Minott Cruger, who knows the challenges a professional woman of colour faces at home and at work and has helped me develop a more balanced, pragmatic, and joyful approach to life. My younger sister, Nadya Robinson, who helped our children continue their learning during lockdown by including them in her on-line fourth-grade class while their school adjusted to the Covid emergency, thereby enabling my own work to continue.

In addition to those who have provided personal and professional support throughout the writing of this book, I also owe much to those whove helped by managing details and logistics: to Tina Smaldone, our department secretary, who augments her professional skills with a wealth of care and compassion and makes the impossible possible; to librarians, especially those at Cornell Universitys Olin and Sibley Libraries, at Hobart and William Smiths W. H. Smith Library, at the City College Library and the Mina Rees Library at CUNY Graduate Center (for their unerring ability to unearth works by a little-read Victorian novelist) and at the Manchester Central Library for helping me access the letters of W. H. Ainsworth. Finally, I acknowledge Hobart and William Smiths provost, Mary Coffey, who encouraged me personally and by example while steering our institution through a pandemic. I sometimes felt alone as I wrote this book. Clearly, I was not.

N ICOLA M INOTT -A H l

Hobart and William Smith Colleges

Geneva, NY

Introduction

Words, carefully chosen, can alter our perception of reality or create an alternative one. A brief visit to a political rally, a Southern Baptist church service in the United States, or a team locker room anywhere will provide ample demonstration that the right language can stir up a crowd and transform it into a focused collective or a mindless mob. As Shelley, Barbauld, Landon, and Blake demonstrate, a poet can transcend the ordinary with keen observations clothed in extraordinary language, for the Romantic poets were more than just dreamers; they asserted the right and responsibility to transform their world. So much of common perception of the English and French novel of the nineteenth century is that it is the antithesis of this thinking; that Victorian novelists wanted to depict their world with kitchen-sink accuracy, and perhaps wring some pathos or social consciousness out of their readers. But this book will argue that William Ainsworth, Victor Hugo, and Alexandre Dumas all wrote novels that were meant to do the very same thing the Romantics set out to do. They wanted to transform the world.