THE SOUL OF POLITICS

2021 by Glenn Ellmers

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of Encounter Books, 900 Broadway, Suite 601, New York, New York, 10003.

First American edition published in 2021 by Encounter Books, an activity of Encounter for Culture and Education, Inc., a nonprofit, tax-exempt corporation.

Encounter Books website address: www.encounterbooks.com

Manufactured in the United States and printed on acid-free paper. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper).

FIRST AMERICAN EDITION

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Ellmers, Glenn, 1966 author.

Title: The Soul of Politics: Harry V. Jaffa and the Fight for America By Glenn Ellmers. Description: First American Edition.

New York : Encounter Books, 2021.

Includes bibliographical references and index. | Identifiers: LCCN 2021001840 (print) LCCN 2021001841 (ebook) | ISBN9781641772006 (Hardcover : acid-free paper) ISBN 9781641772013 (eBook)

Subjects: LCSH: ConservatismUnited States.

Political scienceUnited StatesPhilosophy.

United StatesPolitics and governmentPhilosophy. | Jaffa, Harry V.

Classification: LCC JC573.2.U6 E57 2021 (print) | LCC JC573.2.U6 (ebook) DDC 320.01dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021001840

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021001841

Interior page design and composition by Bruce Leckie

To be a fellow citizen means not only to be able to accept the results of a free election but also to be willing to fight to preserve, protect, and defend the regime of free elections. A community of citizens is a community of those willing to fight for each other. Someone who will not fight for you, when you are willing to fight for him, cannot be your fellow citizen.

Finding the natural aristoi, providing for their education, and discovering the ways and means in particular circumstances to maximize their influence, is the task of political philosophy, whether in the ancient or modern world.

We cannot define our tasks by our powers, for our powers become known to us through performing our tasks; it is better to fail nobly than to succeed basely.

CONTENTS

At first sight, this is a very academic sort of book. It is about a college professor. Although it gives the best account I have read of the events in the life of its subject, Harry Jaffa, it is not mostly about events. Professor Jaffa was born in 1918 and bears the middle name Victor. Neither the victory in the First World War nor in the second comes into play. Jaffa lived through the Great Depression, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War. They come up, but in passing. With the rare exception of a Winston Churchill, the events in the lives of thinkers and writers are ordinary, filled not with battles but with books, not with odysseys except between the study and the classroom.

Nor is the classroom the same kind of place as the dramatic stage. Few professors prepare their classes with a beginning, a middle, and an end through which they climb to a peak of tension, understanding, and exhaustion. If you want to know what a professor thinks about a subject, the academic way is to take the course, which means sitting in a classroom for forty-five hours stretching over four months. Plus, there is plenty of reading and thinking to do outside the classroom. Recounting a lifetime like this can make a boring book.

Yet this book is not boring, because it is not about an ordinary sort of academic. Professor Jaffa was a political thinker in the school of classical political philosophy, and in him political passion was intense, qualified only by a greater devotion to knowledge. He learned from his teacher and from the classics that philosophy begins with the inescapable question: how should we live? This is the pressing form of the fundamental question, what is good?, which itself raises questions both inescapable and urgent. The starting point for Plato and Aristotle is the opinions of ordinary people, especially the most authoritative opinions as they are expressed in the law. Thus, political philosophy.

We know from ancient political philosophy that the examination of the opinions of citizens and their laws can be dangerous, especially to the philosopher. Socrates, the father of political philosophy, was executed for treasons and impieties that he claimed he had not committed. Aristotle fled for his life from Athens to escape the same fate. Have you read the news these days about the hounding of professors from classrooms for the slightest violation of political correctness? Today as in classical times, the study of politics produces casualties. During Professor Jaffas own career, on his own campus, radicals destroyed a building and maimed an employee with a pipe bomb. Professor Jaffa spoke out boldly and at risk against these evils and the college administrators who surrendered to them.

Professor Jaffa did not and would not willingly kill anyone, and he died peacefully at ninety-six. But the combat in which he engaged was fierce because it was consequential. One of Professor Jaffas old friends exclaimed once in writing: who will rid us of this pest a priest? After Henry II uttered those words, some who heard them assassinated Thomas Becket. Professor Jaffa learned nothing from the example of Becket and returned immediately to the attack.

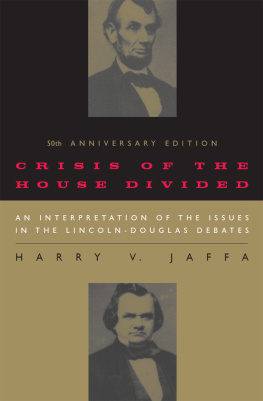

Like that of Socrates, Professor Jaffas kind of philosophy operates very close to home. He had the insight of his life in his late thirties. By accident or providence, Professor Jaffa fell in love with Abraham Lincoln. He had a chance encounter with the text of the Lincoln-Douglas debates, and he saw in them the profundity of a Socratic dialogue. Those debates changed his life, the lives of his students, and the politics of our nation. From Lincoln, Jaffa worked his way back to the founding and discovered things in it that had been forgotten. He resurrected those things and made them compelling for his students, as they had been for the founders who articulated, fought for, and established the meaning of our nation. Professor Jaffa hoped for nothing less than the revival of a scholarship of the politics of freedom, a reversal of the relentless march toward historicism. Only by that means could both freedom and civilization be made safe. Professor Jaffa succeeded with his students, as his teacher had succeeded with him. This he thought proved that a revival was as possible as it was necessary.

The central story of this book is in fact a grand drama involving the life and meaning of the greatest modern republic. Professor Jaffa loved the United States of America on a cosmic scale. He found its justification beyond it, in the heavens, where God or the idea of God influences human actions here below. He saw that the Declaration of Independence appeals to that very place in establishing the ground of our freedom and equality.

This means that Professor Jaffa was not simply a political thinker or simply an American thinker. His interests covered, like the works of Aristotle, the whole sweep of questions available to the human mind. His lifes work was to integrate what he knew into an account of the meaning of his country.