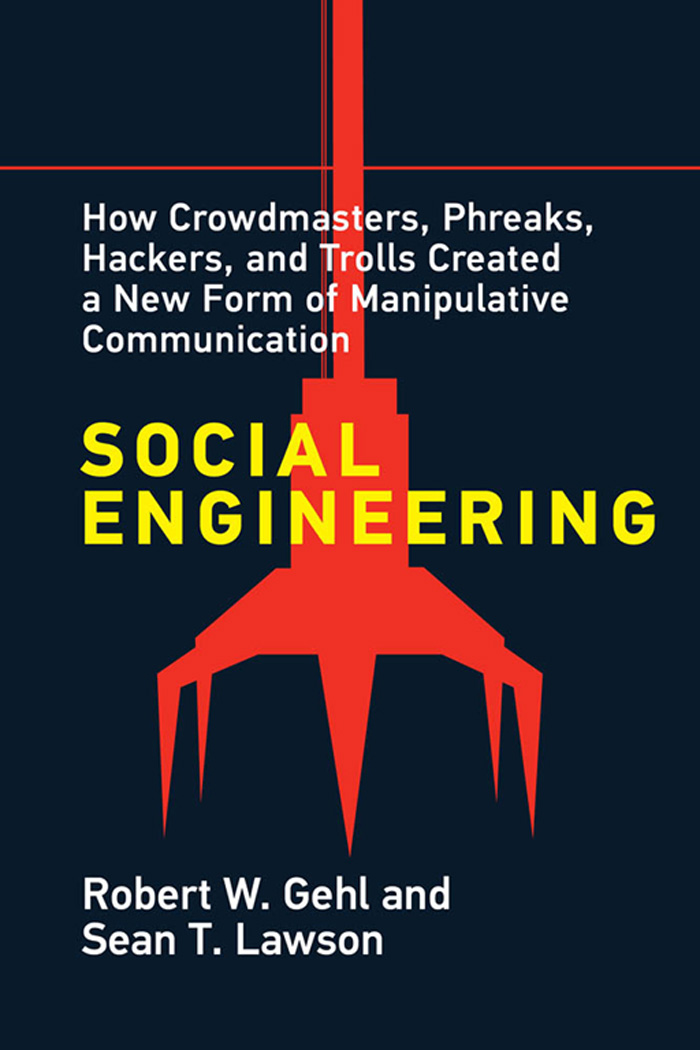

Social Engineering

Social Engineering

How Crowdmasters, Phreaks, Hackers, and Trolls Created a New Form of Manipulative Communication

Robert W. Gehl and Sean T. Lawson

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts | London, England

2022 Robert W. Gehl and Sean T. Lawson

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

The MIT Press would like to thank the anonymous peer reviewers who provided comments on drafts of this book. The generous work of academic experts is essential for establishing the authority and quality of our publications. We acknowledge with gratitude the contributions of these otherwise uncredited readers.

This book was set in ITC Stone Serif Std and ITC Stone Sans Std by New Best-set Typesetters Ltd.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Gehl, Robert W., author. | Lawson, Sean T., 1977author.

Title: Social engineering : how crowdmasters, phreaks, hackers, and trolls created a new form of manipulative communication / Robert W. Gehl and Sean T. Lawson.

Description: Cambridge : The MIT Press, 2022. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021016750 | ISBN 9780262543453 (paperback)

Subjects: LCSH: Social mediaSecurity measures. | Computer networksSecurity measures. | Internet fraud. | Social engineering.

Classification: LCC HM742 .G45 2022 | DDC 364.16/3dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021016750

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

d_r0

This book is dedicated to Teddy and Everett.

Contents

Acknowledgments

The authors of any book are always deeply indebted to all of those folks along the way who provided advice, encouragement, support, and feedback. We are no exception. This project would not have been possible without the generosity of colleagues, friends, and family. We would especially like to thank Margot Opdycke Lamme, Professor Emerita at the University of Alabama, for providing a copy of Doris Fleischmans 1935 speech. Biella Coleman of McGill University offered feedback and encouragement early in the process, as did Walter Scheier at Notre Dame. Hector Postigo provided feedback that was critical in helping us decide just what to call the phenomenon we discuss in the pages that follow: masspersonal social engineering. Guobin Yang helped to shape our thinking by generously sharing with us his chapter, Communication as Translation. Finally, both Emma Briant and Cory Wimberly shared their excellent books on propaganda with us.

We are also thankful to the audience and organizers of several events at which we were honored to present early drafts of this work. These included the 2020 Hackers on Planet Earth (HOPE) conference, the Department of Defense Strategic Multilayer Assessment, and the Critical Genealogies Workshop. At the latter, we especially thank Bonnie Sheehey, Ashley Gorham, Verena Erlenbusch-Anderson, Cory Wimberly, and Colin Koopman for their extensive comments.

Finally, of course, we are grateful for the patience and assistance provided by our editor at the MIT Press, Gita Manaktala, as well as the anonymous reviewers whose comments helped shape and improve this book. Nonetheless, of course, any errors or omissions are all our own.

I would like to thank the Louisiana Board of Regents Endowed Chairs for Eminent Scholars program, which provided funding for this project. The University of Calgary Communication, Media, and Film Department and the Louisiana Tech Communication faculty provided valuable comments on an early version during my Fulbright fellowship. I also had a great conversation with Claire Evans about Susy Thunder and phone phreaking.

I am, as always, in deep debt to my friends, old (Ry, Mony, Brian, and Dan) and new. A new and deep friendship has been made during the writing of this book: Sean, thank you (and Cynthia!) for not only putting up with me but also putting me up during a time of disasters.

Love from my family keeps me going even in the midst of bleak times. My mom, my little brother, the Houf family. And I cannot think of anyone Id rather weather the storm with than Captain TJ and Navigator TJ.

Robert W. Gehl

June 2021

I would like to thank my close friends and family for their patience and support during the process of writing this book, most of which took place during the challenge of a global pandemic. First and foremost, my wife, Cynthia, whose advice and encouragement keeps me going. Rob, my coauthor and friend: thank you for inviting me to be a part of this project and for your patience along the way. Im ever grateful for the chance to learn and grow as a writer through our collaboration. Finally, I, too, must thank Captain and Navigator TJ, who helped keep us all well fed and sane during some tough times early in the project.

Sean Lawson

June 2021

Introduction: The Emergence of Masspersonal Social Engineering

The United States is awash in a disorienting and sometimes deadly digital media environment. People are sharingsometimes purposely, other times without knowing any bettermanipulative information about everything from election results to the effectiveness of medical treatments. Domestic political leaders seek to ride the resulting paranoia and confusion to ever greater power, while foreign governments gleefully stoke divisions and discontent.

Manipulative communication found a home in corporate social media, especially Facebook, Facebooks child company Instagram, and Twitter. These systems were designed to amplify attention-getting messages, whether those messages are cute cat videos or the latest QAnon drops of conspiracy theorizing. Facebook has especially proven to be a willing vehicle for manipulative communication, using its vast data on our likes and preferences to route to us the information that satisfies our desire for affirmation. No matter your political or social tastes, Facebook will deliver a meme that confirms your viewseven if the meme is bullshit. And if Facebooks own algorithms dont deliver a message to its intended audience, the creators of the message can simply pay a small fee to microtarget their ideas to audiences likely to agree with them.

Such manipulative communication erupted in a paroxysm of violence on January 6, 2021. That day, a riotous mob of Donald Trump supporters occupied the US Capitol building. The mob was spurred on by a blatant misinformation campaign, run by Trump and several of his allies (notably Senators Josh Hawley and Ted Cruz), all of whom peddled bullshit about rampant election fraud in the 2020 US presidential campaign.

The Capitol insurrection is a cautionary example of the dangers of manipulative political communication. But, as we will argue, the sorts of manipulative communication that fueled the events of January 6, 2021 are nothing new. Consider, for example, the 2016 US presidential election, which pitted the Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton against the reality-television-star-turned-Republican Donald J. Trump. There are now two well-documented types of manipulation campaigns that took place in the run-up to that election.

First, there were attempts by a foreign government, Russia, to undermine confidence in the election, support Trump at the expense of Clinton, and stoke racial and political divisions among Americans. Thanks to several investigations, the campaign is well documented, its complexity revealed. The operation involved the hacking of email accounts associated with the Democratic National Committee and the Hillary Clinton campaign, theft of data, and the leaking of those data to third parties like WikiLeaks. Russian state media outlets

Next page