F i r s t w e r e a d , t h e n w e w r i t e Nature

i

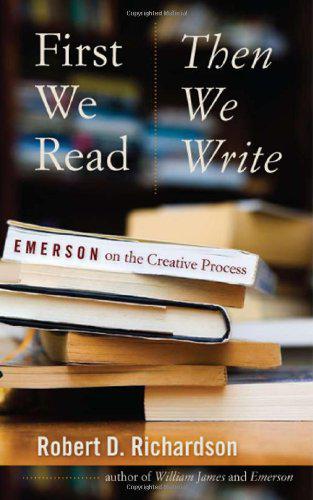

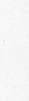

First We Read, Then We Write

ii Contents

e m e r s o n o n t h e C r e a t i v e P r o C e s s By Robert D. Richardson

U n i v e r s i t y o f i o w a P r e s s Iowa City

Nature

iii

University of Iowa Press, Iowa City 52242

Copyright 2009 by Robert D. Richardson

www.uiowapress.org

Printed in the United States of America

Design by Teresa W. Wingfield

No part of this book may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. All reasonable steps have been taken to contact copyright holders of material used in this book. The publisher would be pleased to make suitable arrangements with any whom it has not been possible to reach.

The University of Iowa Press is a member of Green Press Initiative and is committed to preserving natural resources.

Printed on acid-free paper

library of congress cataloging-in-publication data Richardson, Robert D., 1934

First we read, then we write: Emerson on the creative process /

by Robert D. Richardson

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

isbn-13: 978-1-58729-793-9 (cloth)

isbn-10: 1-58729-793-0 (cloth)

1. Emerson, Ralph Waldo, 18031882. 2. Emerson, Ralph Waldo, 1803

1882Knowledge and learning. 3. Authors, American19th century

Biography. 4. Books and reading. 5. Creative writing. 6. Creation (Literary, artistic, etc.) I. Title.

ps1631.r54 2009

814'.3dc22

2008040554

09 10 11 12 13 c 5 4 3 2 1

iv Contents

For Lissa, for Anne, and for Cody Rose

What seas what shores what grey rocks and what islands What water lapping the bow

And scent of pine and the woodthrush singing through the fog

What images return

O my daughter[s].

T. S. Eliot, Marina

Nature

v

vi Contents

Contents

Introduction 1

Reading 7

Keeping a Journal 19

Practical Hints 23

Nature 27

More Practical Hints 33

The Language of the Street 45

Words 49

Sentences 53

Emblem, Symbol, Metaphor 59

Audience 65

Art Is the Path 71

The Writer 77

Epilogue 83

Acknowledgments 87

Notes 89

index 99

Nature

vii

viii Contents

F i r s t w e r e a d , t h e n w e w r i t e Nature

ix

x Contents

Introduction

The first sentence of Ralph Waldo Emersons that reached me still jolts me every time I run into it. Meek young men,

he wrote in The American Scholar, grow up in libraries believing it their duty to accept the views which Cicero, which Locke, which Bacon have given, forgetful that Cicero, Locke, and Bacon were only young men in libraries when they wrote those books.

Writing was the central passion of Emersons life. He considered himself a poet; he wrote what is arguably the best piece ever written on expressionism in literaturean essay called The Poet; he wrote about writersGoethe, Shakespeare, Montaigne and he talked and wrote, especial y in his journals, about the art and the craft of writing. But he never wrote an essay on writing.

One reason he never did may have been that he had impossible, unreachable ambitions as a writer himself. At age twenty-one he turned uncertainly to graduate study in divinity. He found himself longing for the open horizons and welcoming fields of endeavor enjoyed by earlier generations, and longing for a time when entering contestants Nature

were never troubled with libraries of names and dates.

Like many a beginning grad student, he felt life is wasted in the necessary preparation of finding what is the true way, and we die just as we enter it. Graduate study in divinity in 1824, even for a Unitarian, meant almost entirely Bible study; by July, Emerson was reading Nathaniel Lardners History of the Apostles and Evangelists and studying the book of Proverbs in the Old Testament. Proverbs is not a gospel, and it is not a great narrative like Genesis. It is a very minor book, though it does have a prophetic voice and it sits near Ecclesiastes, the Song of Solomon, and Isaiah in the canon.

Emersons heart rose at the prospect of the passive study of scripture. It was his ambition not to annotate but to write one of those books which collect and embody the wisdom of their times. Emerson looked on Solomon as a fellow writer, someone to be imitated, not just venerated. The young Emerson singled out in his journal the proverbs of Solomon, and Bacons and Montaignes essays, and declared, I should like to add another volume to this valuable work. Preposterous as this must appear to the orthodox Christian, it made plain sense to Emerson. But, we say incredulously, what if it was God who was speaking through Solomon? Wel , perhaps he would speak through Emerson also.

It was an aspiration he would claim at age twenty-one only in his private journal, but which he would reclaim, albeit collectively, in the last paragraph of the final essay in his 1850 book Representative Men almost thirty years later.

We too must write Bibles, he writes at the end of his essay on Goethe. His ambition then, from the start, was as phenomenal as it was unwavering.

We may debate his success, but as his young friend Henry Thoreau noted, in the long run men hit only what they aim Na

Int trur

odeuction

at. Emerson also knew, as Epictetus knew, that all things have two handles. Beware of the wrong one. And the Proverbs of Solomon are themselves darkly eloquent about taking the wrong path:

I went by the field of the slothful, and by the vineyard of the man void of understanding:

And, lo, it was all grown over with thorns, and nettles had covered the face thereof, and the stone wall thereof was broken down.

Then I saw, and considered it well: I looked upon it, and received instruction.

Yet a little sleep, a little slumber, a little folding of the hands to sleep:

So shall thy poverty come as one that travelleth, and thy want as an armed man. (Proverbs 24:3034) Emersons immodestalmost indecentambition seems both too high and too abstract to be real, or to be believed; but there was always another side to the man, a side where both his feet are planted in everyday reality, a side of him that often sounds overwhelmed, sometimes desperate, but always determined. A person, he wrote, must do the work with that faculty he has now. But that faculty is the accumulation of past days. No rival can rival backwards. What you have learned and done is safe and fruitful. Work and learn in evil days, in insulted days, in days of debt and depression and calamity. Fight best in the shade of the cloud of arrows.

It is encouraging to learn that writing was often a desperate struggle for Emerson. He came early to the knowledge that every day is the Day of Creation as well as the Day of Judgment. At days end he never felt he had done his best, Na

Inttrure

od uction

never felt he had achieved adequate expression. His best poem, Days, expresses his sense of the accusing sufficiency of every single day and his chagrined feeling that he was not making the best use of his time, that he was claiming the wrong gifts, working the wrong side of the street, and that every day shut down for him on a night of failure.

Daughters of Time, the hypocritic Days,

Next page