For Annie one more time

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Henry Thoreau: A Life of the Mind

Emerson: The Mind on Fire

William James: In the Maelstrom of American Modernism

First We Read, Then We Write: Emerson on the Creative Process

Splendor of Heart: Walter Jackson Bate and the Teaching of Literature

Edward FitzGeralds Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam (introduction and notes by Robert D. Richardson and art by Lincoln Perry)

CONTENTS

There was no center to Edward FitzGeralds life, as his collected works, his letters, and half a dozen biographies make clear. John Banville has observed, in Ancient Light, that all biographies are mendacious. This one, insofar as it is a biography, is no exception. I have deliberately put the Rubaiyat at the center, arranging everything else around it, like potatoes around a roast. The question for a biography is not, is it true? It cant be true. The question should be, is it useful? I have not invented anything, I have not falsified any detail, at least not knowingly, but I have selected material with an eye to showing that a writers life may have a great accomplishment to its credit even if the writer in question never fully saw it, or allowed himself to accept it, or organized his life for it.

I am grateful to Coleman Barks, who thought I could do it; to Lincoln Perry, who realized the visual links between the worlds of eleventh-century Persia, nineteenth-century England, and contemporary America; and to Alireza Taghdarreh, whose translation of Walden into Persian demonstrates how the Silk Road of the mind is now a two-way street. I am also grateful to Philip Kowalski and Callie Garnett for help with illustrations.

I am also more grateful than I can say to Will Lippincott, who believed in this book from the start, and to George Gibson, my old-style hands-on editor, whose attentions have improved every page in this book. And I am grateful above all to Annie, who is the source of all the light I have.

OMAR KHAYYAM AND HIS RUBAIYAT

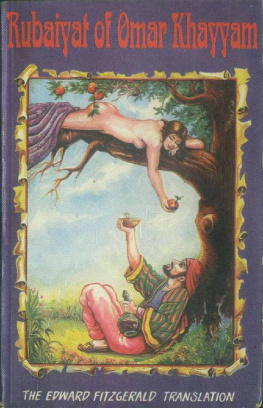

One day in the summer of 1861 there appeared in a London bookstores penny box a small paperbound volume of old Persian quatrainscalled rubaiyat in Persianattributed to the eleventh-century astronomer-mathematician-poet Omar Khayyam, and rendered into English by an anonymous Victorian writer later revealed to be one Edward FitzGerald. This slender volume, a pamphlet really, which had been published in 1859, but which had not sold or been read, was to have more success than any volume of poetry ever published in English. It begins,

Awake! For Morning in the Bowl of Night

Has flung the Stone that puts the Stars to Flight:

And Lo! The Hunter of the East has caught

The Sultans Turret in a Noose of Light.

One of the first influential readers of Edward FitzGeralds Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam was the Victorian art critic John Ruskin, who sat down in 1863 and wrote a short note to the author/translator whose name did not appear anywhere in the book. My dear and very dear Sir, Ruskin wrote. I do not know in the least who you are, but I do with all my soul pray you to find and translate some more of Omar Khayyam for us. I never didtil this dayread anything so glorious, to my mind, as this poem.

Ruskins enthusiasm for

The Persian originals and their Victorian English versions offer a modern reader an accessible, appealing, sensuous, and above all a Lucretian or Epicurean worldview, an outlook based on respect for nature and a principled resistance to the consolations of organized religion. The Rubaiyat is exotic and familiar at the same time. Originally written in Farsi, Khayyams separate and unrelated quatrains, of which many hundreds have survived, are a great if sometimes neglected achievement of the last phase of the Golden Age of Islamthe eighth through the middle of the eleventh century C.E. an era of astonishing intellectual and artistic achievement in the Middle East at a time when the barbarian West was still sunk in the Dark Ages. Reading FitzGeralds Rubaiyat today suggests that there may be an alternative to the clash of civilizations idea that the culturally Christian West and the culturally Islamic Middle East are doomed to endless conflict.

What Omars quatrains and FitzGeralds English versions seem to demonstrate is that just as Nishapur (Omars birthplace and the site of his tomb) is a crossroads city on the old Silk Road (and the only city which the north and south Silk Road routes had in common) so Omars and FitzGeralds poems lie at the intersection of medieval and modern, as well as at the intersection of East and West, at the very crossroads between Christian and Islamic civilization. The long continued interest in the Rubaiyat, both in the East and in the West, suggests that instead of an inevitable clash, there again could be, as there has already been, within limits, an attainable but not yet attained convivencia or convivium, a way to live together.

FitzGeralds Rubaiyat and the Persian quatrains from which FitzGeralds masterpiece was built are urban poetry, city poetry, as far from Jeffersonian or Wordsworthian ideals of the self-sufficient farmer and the wonders of nature as it is possible to get. In FitzGeralds rendering, the quatrains are also anti-Victorian and anti-Calvinist. Omars medieval Persian work and FitzGeralds interest in it also illustrate just the opposite of Henri Pirennes famous thesis, which was that the advent of Islam pushed the West into the Dark Ages. What actually happened was that the Dark Ages witnessed a growing knowledge in the West of Islam and its achievements in philosophy, medicine, and mathematics, knowledge that paved the way for the Western recovery of the classics and the Renaissance of learning.

FitzGeralds Rubaiyat is one of the great translations in world literature, on a par with the Victorian England.

In FitzGeralds hands, individual Persian quatrains coalesced into one of the most moving and most often cited modern poetic statements about loss, longing, and nostalgia. The imagery of the Rubaiyat is wild, colorful, and memorable. It is a proto-modern achievement, hanging just on the lip of modernity. The Rubaiyats opening image is comparable in boldness and originality to the opening image of T. S. Eliots The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock. The Rubaiyat opens with the lines quoted at the start of this chapter:

Awake! For Morning in the Bowl of Night

Has flung the Stone that puts the Stars to Flight:

Eliots opening image in Prufrock could be the evening of Omars day:

Let us go then, you and I,

When the evening is spread out against the sky

Like a patient etherized upon a table;

And just look at the bravado and the Yeatsian passion of the quatrain that is third from the end in all editions of the Rubaiyat:

Ah love! Could you and I with Fate conspire

To grasp this sorry Scheme of Things entire,

Would we not shatter it to bits and then

Re-mould it nearer to the Hearts Desire!

_____

It is a long way from Omar Khayyam to Edward FitzGerald, from eleventh-century Persia to nineteenth-century England, and FitzGeralds transformation of the Persian originals has an almost miraculous poetic quality. Here, for example, is a literal translation of one Persian quatrain in the Oxford manuscript that was FitzGeralds chief source.

Since no one can Tomorrow guarantee,

Next page