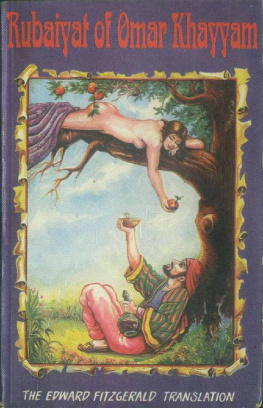

Fitzgerald (trans.) - Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

Here you can read online Fitzgerald (trans.) - Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2013, publisher: Jaico Books, genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

- Author:

- Publisher:Jaico Books

- Genre:

- Year:2013

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Rubiyt

of Omar

Khayyam

CORDON ROSS

Calcutta Hyderabad Madras

1948 by Jaico Publishing House

RUBAIYAT OF

OMAR KHAYYAM

ISBN 81-7224-227-1

This Book is NOT a digest or condensation. It contains the complete text of Edward FitzGerald's first and fifth versions.

Tenth Jaico Impression: 1980

Eleventh Jaico Impression: 1990

Twelveth Jaico Impression: 1993

Published by

Ashwin J. Shah

Jaico Publishing House

121, M.G. Road

Bombay-400 023.

Printed By:

R.N. Kothari

Konam Printers,

Diana Talkies Lane,

Tardeo, Bombay - 400 034.

RUBIYT OF

OMAR KHAYYAM

It is said that when Thomas Hardy lay dying in his eighty-eighth year, he asked to have one particular stanza read to him. It was the verse which runs:

O Thou, who Man of baser Earth didst make, And ev'n with Paradise devise the Snake : For all the Sin wherewith the Face of Man I s blackenedMan's forgiveness giveand take!

LVIII.

INTRODUCTION

W HEN he was horn at Naishapur in Khorassan, some time during the latter half of the 11th century, he was called Ghiyathuddin Abulfath Omar bin Ibrahim AlKhayyami. Reduced to its practical origins, the sonorous syllables indicated nothing more than that the child was the son of one Abraham, or Ibrahim, the tentmaker. The boy, familiarly known as Omar, seems to have followed his father's trade. From tentmaking he graduated to science and mathematics, and in his day he was far better known as a mathematician and astronomer than as a poet. He wrote a standard work on algebra; he revised the astronomical tables; he prompted the Persian Sultan Malik-Shah to make a drastic reform of the calendar.

During the few intervals when he was free of his computations, Omar indulged himself in the pleasures of poetry. He celebrated two intoxicants: verse and the vine. Before he died in 1123 he had composed some five hundred epigrams in quatrains, or rubais, peculiar in rhyme and pungent in effect. The stanzas were, for the most part, independent; they embodied a terse and self-contained idea. But they were connected, if not unified, by a central philosophy: a vigorous, free-thinking hedonism, a casual but frank appeal to enjoy the pleasures of life without too much reflection.

For six centuries Omar's work was unknown to the western world. It remained for a secluded English country gentleman to establish the Persian poet-mathematician among the glories of literature. Edward FitzGerald was born in the village of Bredfield on March 31, 1809, into a well-to-do family. Educated at Trinity College, Cambridge, where he became a friend of Thackeray, FitzGerald did the leisurely studying and traveling which was expected of him, cultivated music and botany, and, even as a young man, was relieved when he was permitted to retire to the Suffolk countryside. There he settled himself quietly, devoted his days to his friends and his flowers, and led a pleasantly unproductive life until his late forties.

In his fiftieth year, FitzGerald published a little paper-bound pamphlet of translations which he called The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam. The Pamphlet was published anonymously; it attracted little attention. A year later, in 1860, the poets Swinburne and Rossetti discovered the poem. But, legend to the contrary, the work did not thereupon leap into popularity. Eight years passed before a second edition seemed advisable.

Suddenly the poem became a favourite; the care-free quatrains of the eleventh-century Persian were used as a challenge by the nineteenth-century under-graduates, repeated by rebellious lovers, and flung out as a credo by the men and women who were growing restless if not yet insurrectionary. There had always been an undercurrent, of protest against the rigid moral earnestness of the period. The Rubaiyat served as a small but concentrated expression of the revolt against Victorian conventions, the prevailing smugness, the false acquiescence and hypocritical prudery. Religion had been confronted by science; noble ideals had come into conflict with practical necessity; roaring machinery was threatening to dispel the once pervasive sweetness and light. The message of FitzGerald's Rubaiyat was something of a slogan and something of an escape; it turned imperial commercialism to an idealized paganism. Half-defiantly, half desperately the younger men and vsomen made FitzGerald-Omar a vogue. Perhaps the most quoted quatrain of the century was:

A Jug of Wine, a Loaf of Breadand Thou

Beside me singing in the Wilderness

Oh, Wilderness were Paradise enow!

Here was an infectious panacea, half tonic, half opiate. It was not so much a compromise of values as a combination of desirables: an avoidance of ordinary existence and a participation in a richer, if somewhat unreal, life. This was the opposite of Mrs. Grundys middle-class taboos; this was a very denial of negations. Wine, woman, and song were affirmed and glorified in a mounting paean of pleasure. A Persian Ecclesiastes, through the medium of a staid English squire, assured a perplexed generation that all was vanity; that the glories of this world are better than Paradise to come; that it is wise to take the cash and let the credit go; that life is a meaningless game played by helpless pieces; that worldly ambitions turn into ashes; that in the endan end which comes all too quicklywine is a more trustworthy friend and a better comforter than all the philosophers.

Thrust into undesired notice by The Rubaiyat, FitzGerald attempted to live up to his reputation for a while.

He published translations of the Agamemnon and the two Oedipus tragedies of Sophocles; he wrote a biography of Bernard Barton, his father-in-law and friend of Charles Lamb; he made a dompilation of the homely verse of George Crabbe. entitled Readings from Crabbe. But he was not designed to be an Eminent Victorian. He was, even among retired gentlemen, unusually reticent, an idle fellow, one whose friendship were more like loves and his wit was kept for private communications. It was not until the letters of Old Fitz were published that FitzGerald's personal charm was revealed. He sank back into semi-obscurity as though it were a comfortable couch, and died, almost a quarter of a century after the publication of The Rubaiyat, on June 14, 1883. His end was characteristically calm. He slipped from life pain-Tessly, almost imperceptibly.

Appreciation of Omar-FitzGerald continued to grow. Tennyson wrote a reminiscent poem lauding the golden Eastern lay of that large infidel, your Omar, and hoping that FitzGerald would welcome the verses not so much for their own sake as a tribute from

When, in our younger London days,

You found some merit in my rhymes,

And I more pleasure in your praise.

The Persian poem which seven centuries had neglected came to life as a permanent part of English literature. Elihu Vedder emphasized, and even overstressed, its allegorical implications with his famous symbolic drawings.

Translations appeared in German, Italian, French, Danish, and Hungarian. Liza Lehmanns song cycle In a Persian Garden was a performer's show-piece and a popular favorite at the turn of the century. Omar became a cult; commentators placed him at the head of literature of agnosticism. The quatrains were enthusiastically, if inconsistently, compared to the choruses in the Greek dramas, the hopeless outcries of Job, and the irresponsible drinking-songs of Anacreon. It is said that when Thomas Hardly lay dying in his eighty-eighth year, he asked to have one particular stanza read to him. It was the verse which runs:

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam»

Look at similar books to Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.