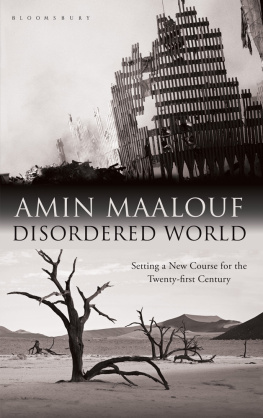

Amin Maalouf is a Lebanese journalist and writer. He was formerly director of the weekly international edition of the leading Beirut daily an-Nahar, and editor-in-chief of Jeune Afrique. He now lives with his wife and three children in Paris.

Samarkand won the Prix des maisons de la presse and The Rock of Tanios was the 1993 winner of the Prix Goncourt.

Russell Harris is a translator and researcher who lives in Amsterdam.

Maaloufs novels recreate the thrill of childhood reading, that primitive mixture of learning about something unknown or unimagined and forgetting utterly about oneself His is a voice which Europe cannot afford to ignore

Claire Messud, the Guardian

LEO THE AFRICAN

THE FIRST CENTURY AFTER BEATRICE

THE ROCK OF TANIOS

THE GARDENS OF LIGHT

Published by Hachette Digital

ISBN: 978-0-74813-124-2

All characters and events in this publication, other than those clearly in the public domain, are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Copyright Amin Maalouf 1989

Translation copyright Quartet Books 1992

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

Hachette Digital

Little, Brown Book Group

100 Victoria Embankment

London, EC4Y 0DY

www.hachette.co.uk

Contents

To my Father

Look round thee now on Samarcand,

Is she not queen of earth? her pride

Above all cities? in her hand

Their destinies?

Edgar Allan Poe (1809-49)

At the bottom of the Atlantic there is a book. I am going to tell you its history.

Perhaps you know how the story ends. The newspapers of the day wrote about it, as did others later on. When the Titanic went down on the night of 14 April 1912 in the sea off the New World, its most eminent victim was a book, the only copy of the Rubaiyaat of Omar Khayyam, the Persian sage, poet and astronomer.

I shall not dwell upon the shipwreck. Others have already weighed its cost in dollars, listed the bodies and reported peoples last words. Six years after the event I am still obsessed by this object of flesh and ink whose unworthy guardian I was. Was I, Benjamin O. Lesage, not the one who snatched it from its Asian birth-place? Was it not amongst my luggage that it set sail on the Titanic? And was its age-old journey not interrupted by my centurys arrogance?

Since then, the world has become daily more covered in blood and gloom, and life has ceased to smile on me. I have had to distance myself from people in order to hear the voice of my memory, to nurture a naive hope and insistent vision that tomorrow the manuscript will be found. Protected by its golden casket, it will emerge from the murky depths of the sea intact, its destiny enriched by a new odyssey. People will be able to finger it, open it and lose themselves in it. Captive eyes will follow the chronicle of its adventure from margin to margin, they will discover the poet, his first verses, his first bouts of drunkenness and his first fears; and the sect of the Assassins. Then they will stop, incredulous, at a painting the colour of sand and emerald.

It bears neither date nor signature, nothing apart from these words which can be read as either impassioned or disenchanted: Samarkand, the most beautiful face the Earth has ever turned towards the sun.

Pray tell, who has not transgressed Your Law?

Pray tell the purpose of a sinless life

If with evil You punish the evil I have done

Pray tell, what is the difference between You and me?

OMAR KHAYYAM

Sometimes in Samarkand, in the evening of a slow and dreary day, city dwellers would come to while the time away at the dead-end Street of Two Taverns, near the pepper market. They came not to taste the musky wine of Soghdia but to watch the comings and goings or to waylay a carouser who would then be forced down into the dust, showered with insults, and cursed into a hell whose fire, until the end of all time, would recall the ruddiness of the wines enticements.

Out of such an incident the manuscript of the Rubaiyaat was to be born in the summer of 1072. Omar Khayyam was twenty-four and had recently arrived in Samarkand. Should he go to the tavern that evening, or stroll around at leisure? He chose the sweet pleasure of surveying an unknown town accompanied by the thousand sights of the waning day. In the Street of the Rhubarb Fields, a small boy bolted past, his bare feet padding over the wide paving slabs as he clutched to his neck an apple he had stolen from a stall. In the Bazaar of the Haberdashers, inside a raised stall, a group of backgammon players continued their dispute by the light of an oil lamp. Two dice went flying, followed by a curse and then a stifled laugh. In the arcade of the Rope-Makers, a muleteer stopped near a fountain, let the cool water run in the hollow formed by his two palms, then bent over, his lips pouting as if to kiss a sleeping childs forehead. His thirst slaked, he ran his wet palms over his face and mumbled thanks to God. Then he fetched a hollowed-out watermelon, filled it with water and carried it to his beast so that it too might have its turn to drink.

In the square of the market for cooked foods, Khayyam was accosted by a pregnant girl of about fifteen, whose veil was pushed back. Without a word or a smile on her artless lips, she slipped from his hands a few of the toasted almonds which he had just bought, but the stroller was not surprised. There is an ancient belief in Samarkand: when a mother-to-be comes across a pleasing stranger in the street, she must venture to partake of his food so that the child will be just as handsome, and have the same slender profile, the same noble and smooth features.

Omar was lingering, proudly munching the remaining almonds as he watched the unknown women move off, when a noise prompted him to hurry on. Soon he was in the midst of an unruly crowd. An old man with long bony limbs was already on the ground. He was bare-headed with a few white hairs scattered about his tanned skull. His shouts of rage and fright were no more than a prolonged sob and his eyes implored the newcomer.

Around the unfortunate man there was a score of men sporting beards and brandishing vengeful clubs, and some distance away another group thrilled to the spectacle. One of them, noticing Khayyams horrified expression called out reassuringly, Dont worry. Its only Jaber the Lanky! Omar flinched and a shudder of shame passed through him. Jaber, the companion of Abu Ali! he muttered.

Abu Ali was one of the commonest names of all, but when a well-read man in Bukhara, Cordova, Balkh or Baghdad, pronounced it with such a tone of familiar deference, there could be no confusion over whom they meant. It was Abu Ali Ibn Sina, renowned in the Occident under the name of Avicenna. Omar had not met him, having been born eleven years after his death, but he revered him as the undisputed master of the generation, the possessor of science, the Apostle of Reason.

Khayyam muttered anew, Jaber, the favourite disciple of Abu Ali!, for, even though he was seeing him for the first time, he knew all about the pathetic and exemplary punishment which had been meted out to him. Avicenna had soon considered him as his successor in the fields of medicine and metaphysics; he had admired the power of his argument and only rebuked him for expounding his ideas in a manner which was slightly too haughty and blunt. This won Jaber several terms in prison and three public beatings, the last having taken place in the Great Square of Samarkand when he was given one hundred and fifty lashes in front of all his family. He never recovered from that humiliation. At what moment had he teetered over the edge into madness? Doubtless upon the death of his wife. He could be seen staggering about in rags and tatters, yelling out and ranting irreverently. Hot on his trail would follow packs of kids, clapping their hands and throwing sharp stones at him until he ended up in tears.