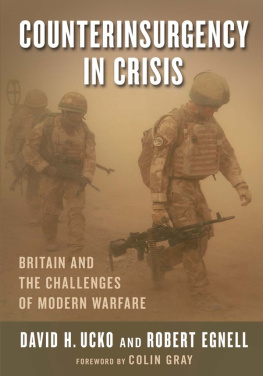

COUNTERINSURGENCY IN CRISIS

Columbia Studies in Terrorism and Irregular Warfare

COLUMBIA STUDIES IN TERRORISM AND IRREGULAR WARFARE

Bruce Hoffman, Series Editor

This series seeks to fill a conspicuous gap in the burgeoning literature on terrorism, guerrilla warfare, and insurgency. The series adheres to the highest standards of scholarship and discourse and publishes books that elucidate the strategy, operations, means, motivations, and effects posed by terrorist, guerrilla, and insurgent organizations and movements. It thereby provides a solid and increasingly expanding foundation of knowledge on these subjects for students, established scholars, and informed reading audiences alike.

Ami Pedahzur, The Israeli Secret Services and the Struggle Against Terrorism

Ami Pedahzur and Arie Perliger, Jewish Terrorism in Israel

Lorenzo Vidino, The New Muslim Brotherhood in the West

Erica Chenoweth and Maria J. Stephan, Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Resistance

William C. Banks, New Battlefields/Old Laws: Critical Debates on Asymmetric Warfare

Blake W. Mobley, Terrorism and Counterintelligence: How Terrorist Groups Elude Detection

Guido Steinberg, German Jihad: On the Internationalization of Islamist Terrorism

Michael W. S. Ryan, The Deep Battle: Decoding Al-Qaedas Strategy Against America

DAVID H. UCKO AND ROBERT EGNELL

COUNTERINSURGENCY IN CRISIS

Britain and the Challenges of Modern Warfare

Columbia University Press / New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2013 David H. Ucko and Robert Egnell

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-53541-0

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ucko, David H.

Counterinsurgency in crisis : Britain and the challenges of modern warfare / David H. Ucko and Robert Egnell.

pages cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-231-16426-9 (cloth : alk. paper)ISBN 978-0-231-53541-0 (ebook).

1. CounterinsurgencyGreat Britain. 2. CounterinsurgencyIraqBasra. 3. CounterinsurgencyAfghanistanHelmand. 4. Iraq War, 20032011Participation, British. 5. Afghan War, 2001Participation, British. 6. Great BritainHistory, Military21st century. I. Egnell, Robert. II. Title.

U241.U255 2013

355.02180941dc23

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

JACKET DESIGN: James Perales

JACKET IMAGE: Copyright 2013 Corbis

References to websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing.

Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

CONTENTS

Colin S. Gray

This book is not a comfortable read for a British strategist like myself. David Ucko and Robert Egnell are scholarly and measured in their treatment of the British experience with counterinsurgency, but they are all the more lethal as a consequence. British strategic effectiveness through counterinsurgency endeavors in the 2000s has been distinctly unimpressive. Indeed, it has been so unimpressive that the investigator is all but spoiled for choice in allocating blame. Although Counterinsurgency in Crisis should be read primarily as a careful study of the British experience of counterinsurgency in the 2000s in Iraq and Afghanistan, it speaks volumes to subjects with wide meaning. Specifically, the authors have much to say of high importance about our understanding and misunderstanding of strategy in its relation to tactics. They also raise and discuss basic vital questions pertaining to the relationship between counterinsurgency and war. These topics can seem to be merely scholars conceptual playthings, but one should not be fooled into making such a dismissive judgment. Strategic theory is about strategic practice, and conceptual understanding of what it is that we believe we are doing in counterinsurgency is critical for our performance and its consequences.

As a Briton, one may not find it agreeable to be told that ones national strategic performance in the 2000s can be characterized as an unpleasant combination of swagger and unpreparedness, in the authors tellingly apposite phrase. Unfortunately, these words are exactly right, painful though it is for me to agree with them. There are villainsor perhaps only incompetentseverywhere. The British public is rightly proud of the bravery shown by our lads and lasses in extremely difficult circumstances. But the generally negative rating given in Britain today to the protracted counterinsurgency (and attempted stabilization) experience in the 2000s is not yet suffused with appropriate understanding of why things went so badly wrong for British forces in both Iraq and Afghanistan. This book explains graphically the contextual challenges that the British state sought to meet, but it leaves the reader in no doubt whatsoever that many of the British counterinsurgency troubles in the 2000s were truly self-inflicted.

Counterinsurgency in Crisis is a genuinely important book in its ability to deal fairly but uncompromisingly with two protracted cases of counterinsurgency in both conceptual and historical context. Some of the British problem undoubtedly was particular to Britain, but much was not. This excellent study can be read as an audit of counterinsurgency effort that happens to be focused on Britain. One learns here about counterinsurgency, not just about Britain and counterinsurgency. The shortlist of villains responsible for the lack of quality in British strategic performance is well populated. Accepting the risk of apparent overstatement, I need to cite recent British weakness at every level of endeavor: vision of desired identity and role (culture), foreign policy, strategy, and tactical military competence. Ucko and Egnell reveal high British ambition for a continuing global role as loyal first lieutenant to Uncle Sam but also show British inability to think strategically with any rigor about what such a role demands. The fundamental structure and logic of strategy provide the conceptual forensic tools most readily suited to economical dissection of the British problem with counterinsurgency in the 2000s. To be plain,

Britain was proud of its believed ability to punch above its weight in the world, particularly as an ally in the special relationship with the United States (a romanticized status invented by Winston Churchill)overconfident in its ability to muddle through and behave adaptively to whatever came along, even when British assets were desperately short.

British foreign policy ambition has not adjusted fully to the countrys reduced circumstances.

Grand and military strategy have largely been missing as direction for British action. In notable part, this absence is attributable to the fact that the classic logical structure of strategic reasoning (ends, ways, and meanseffected in the dim light of some dubious assumptions) simply has not been applied in official decision making and subsequent behavior.