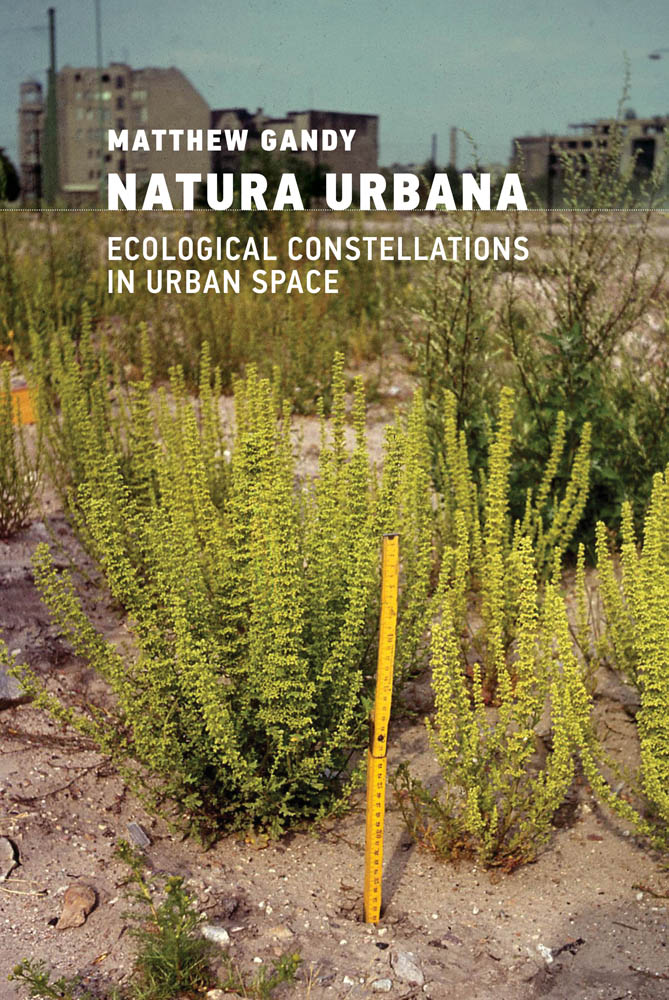

Natura Urbana

Natura Urbana

Ecological Constellations in Urban Space

Matthew Gandy

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2022 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

The MIT Press would like to thank the anonymous peer reviewers who provided comments on drafts of this book. The generous work of academic experts is essential for establishing the authority and quality of our publications. We acknowledge with gratitude the contributions of these otherwise uncredited readers.

This book was set in Bembo Book MT Pro by New Best-set Typesetters Ltd.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Gandy, Matthew, author.

Title: Natura urbana : ecological constellations in urban space / Matthew Gandy.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : The MIT Press, [2022] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021008640 | ISBN 9780262046282 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Urban ecology (Sociology) | Human ecology. | Environmentalism.

Classification: LCC HT241 .G36 2022 | DDC 304.2dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021008640

10987654321

d_r0

Contents

Preface

Writing a book about urban nature has been an interesting journey, not just to specific places, but also through different fields of knowledge. Reflecting on this topic has involved a kind of excavation or even reinterpretation of my own memories. When I started my graduate studies in the late 1980squite a long time ago nowI knew that I was interested in the broad field of urban environmental change and was drawn towards two analytical pathways in particular: the metabolic and the ecological. In November 1989 I had attended a workshop on urban ecology held in the island city of West Berlin, just a few days after the fall of the Wall. In the event, however, I moved in a metabolic direction with much of my earlier work, linking in particular with the study of infrastructure, whilst the other strandthe ecologicalremained somewhat dormant (to deploy a botanical metaphor) until the early 2000s, after I returned to Berlin as a research fellow at the Humboldt University. Back in Berlin, I became fascinated by the interstitial landscapes that were filled with traces of nature, memory, and cultural artifacts. These Brachen, with their distinctive ecological assemblages, became a focal point for a new phase of work on urban nature.

At the time of my doctoral studies, the field of human geography, which remains my primary disciplinary anchor point, seemed to be pulling in several different directions: the spatial science tradition was still very present, newly emboldened by advances in the technical manipulation of data; the confidence of neo-Marxian perspectives that had emerged in the 1970s and 1980s was beginning to ebb; and a host of effervescent new voices was emerging that could be loosely grouped under the umbrellas of cultural, feminist, and postcolonial approaches. From the vantage point of early 2021, however, whilst all of these broad strands of work persist in different forms, the ontological critique of the bounded human subject has become much more fully developed, along with a more incisive (though still only partial) shakeup of the colonial historiographies that underpin the modern discipline of geography.

In writing this book I have been reflecting on various points of intersection between urban ecology and diverse literatures such as ecocriticism, critical legal theory, and forensic science. Part of the challenge in writing this book has been to explore whether a broadly neo-Marxian framework, originating under the metabolic lens of urban political ecology, can withstand a sustained engagement with other intellectual traditions, and whether a new conceptual synthesis for the study of urban ecology and urban nature might be achievable.

My thinking about urban nature has been greatly enriched over the last few years by my involvement in local environmental issues in inner London: working with other enthusiasts to provide data for a biodiversity action plan made me reflect on the curious journey of biodiversity discourse from the UN Rio Summit of 1992 to the deprived inner London borough of Hackney; my role as a citizen scientist has involved sending in my own records of invertebrates to regional recorders (and experiencing the delight of seeing my dots appear on local distribution maps); my involvement in a campaign to stop a luxury housing development that would have damaged a local nature reserve introduced me to the ecological realpolitik of scientific expertise for sale and the legal labyrinth of a judicial review process; and in giving guided walks and public talks on aspects of urban biodiversity I have gained a sense of what aspects of nature interest people in the heart of the city. In terms of my London-based experiences of urban nature I would especially like to thank the locally based experts who have brought the city to life: Tristan Bantock, Tony Butler, Annie Chipchase, and Russell Miller.

The literature on urban nature is vast, diverse, and rapidly changing, with multiple historiographies, networks, and traditions. I am aware of the frustration that is felt in other language spheres that are routinely overlooked, or even inadvertently replicated, within the increasingly dominant Anglo-American realm of environmental knowledge production. In terms of research on urban nature, urban ecology, and critical landscape studies this is especially significant for debates long under way within the French and German language spheres, and I have tried to ensure some degree of nuance in my account of this wider intellectual field. In terms of the gravitational pull of urban research I am clearly anchored in Anglo-American academic traditions, but over recent years I have developed outlying connections to India, France, Belgium, Portugal, and especially Germany.

My research has relied on many libraries and other resources including the Natural History Museums in Berlin and London, the British Library, Cambridge University libraries, the Graduate School of Design at Harvard University, the Tamil Nadu archives, the Archives Nationales in Paris, and the University College London libraries. The Biodiversity Heritage Library has proved an amazing resource for my research, especially during the closure of many libraries under the Covid-19 lockdowns. I have also drawn widely on semistructured interviewsframed around clearly defined questionsbut also on an array of more informal conversations that have enriched many aspects of the work. In writing this book I have realized how much emphasis I place on site visits, serendipitous encounters, and forms of attentive observation as I fill my notebooks with thoughts and ideas. There is an attachment to pavement ecologies that permeates my textperhaps the Americanized sidewalk ecologies sounds more poeticrooted in my fascination with the flora and fauna all around us. As I was writing this book in the summer of 2020, for instance, I noticed a strange-looking wasp trapped against the inside of my kitchen window, so I took a photo and let it go. With the help of Italian entomologists I discovered it was something quite unusual, the nationally scarce and elusive Lestiphorus bicinctus that has a liking for dunes, rough grassland, and brambly places. I got back to my text with a flush of further enthusiasm.

Next page