First published July 2002 by Oxford University Press for

The International Institute for Strategie Studies

Arundel House, 1315 Arundel Street, Temple Place, London WC2R 3DX

www.iiss.org

This reprint published by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

For the International Institute for Strategie Studies

Arundel House, 1315 Arundel Street, Temple Place, London WC2R3DX

www.iiss.org

Simultaneously published by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

The International Institute for Strategie Studies 2002

Director John Chipman

Editor Mats Berdal

Assistant Editor Matthew Foley

Production Shirley Nieholls

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical or photo-copying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of The International Institute for Strategic Studies. Within the UK, exceptions are allowed in respect of any fair dealing for the purpose of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of the licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data

ISBN 0-19-851668-1

ISSN 0567-932x

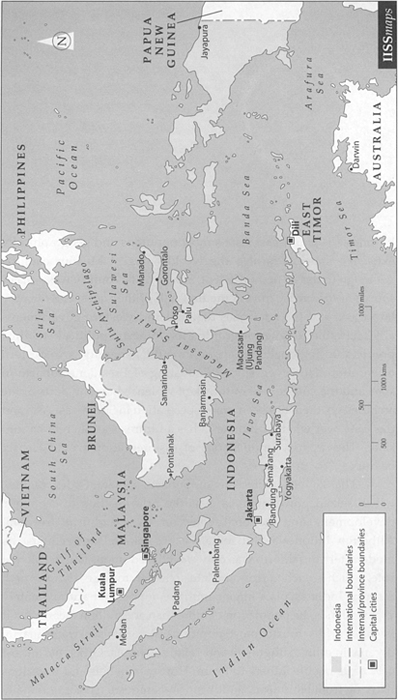

Indonesia is South-east Asia's most populous and geographically extensive state. It is also the world's largest Muslim country. Although under its first president, Sukarno, the country was a major source of insecurity during the first half of the 1960s, between the late 1960s and the late 1990s regional and Western governments alike felt able to take for granted its domestic political stability, predictable regional foreign policy and generally pro-Western orientation. However, since the ousting of President Suharto in 1998 and the subsequent outbreak of violence in many parts of the archipelago, there has been much speculation in South-east Asia and the West over whether Indonesia has a future as a coherent nation-state. The security implications of disintegration would clearly be huge.

The key characteristic of Suharto's New Order regime, which seized power in 1965, was the prioritisation of economic development and national cohesion over political freedom. Although Indonesia had tentative pre-colonial antecedents, its modern territorial form was only established under Dutch colonial rule, which stretched from the late sixteenth to the early twentieth century. Indonesia is a huge country, composed of approximately 13,000 islands. Its population of more than 200 million means that it is the world's fourth most populous state. It is extraordinarily diverse in ethnic, linguistic and religious terms. Officially, almost 90% of its people adhere to Islam. However, beliefs and traditions deriving from Hinduism, Buddhism and animism have traditionally

diluted the Islamic practices of many Indonesians. A sizeable Christian minority is concentrated in eastern Indonesia, Bali's population is largely Hindu and an ethnic Chinese minority, though amounting to no more than a few per cent of the total population, controls a large part of the economy.

Although Indonesia's population is preponderantly Muslim, the military-dominated New Order enforced a sense of national unity through the state philosophy of Pancasila, which emphasises religious tolerance. Despite the national motto of Unity in Diversity, however, there were serious tensions beneath the surface of Suharto's Indonesia. The New Order ran the country as a rigorously centralised empire, in which the provinces lacked significant economic let alone political autonomy. Although civilian technocrats played important parts in the government, under the system of dwi fungsi (dual function) the armed forces dominated at both national and local levels, providing cabinet ministers, provincial governors and district heads. There were growing pressures from resource-rich regions for a fairer distribution of national wealth, and the government in Jakarta faced armed struggles by provincial independence movements in Irian Jaya (now Papua) and Aceh. In East Timor, a former Portuguese colony invaded and occupied by Indonesia in 1975, a larger-scale resistance struggle attracted international sympathy. By the 1990s, there was also more generalised agitation for greater political freedom. Huge social and economic inequities persisted. Government corruption was endemic, starting with the president and his family.

The regional economic crisis in 199798 dramatically reinforced pressure for political change. Following Suharto's loss of support from the political and military establishment, the installation in May 1998 of an interim administration led by B. J. Habibie opened the way for democratic parliamentary elections in June 1999, and for the appointment of a new president, Abdurrahman Wahid, the following October. However, Abdurrahman proved incapable of managing his coalition government effectively and, harried by the still-influential armed forces as well as by his political opponents, he only survived as president until July 2001, when parliament replaced him with his vice-president, Megawati Sukarnoputri.

Four years after Suharto was forced to step down, Indonesia's d mocratisation remains incomplete. Party politics has been revived, but there is little respect for the rule of law: the rich and powerful figures guilty of large-scale corruption have mainly escaped justice. Security-sector reform has a long way to go, and the military is still an important power-broker. Civilian political control of the armed forces remains nominal: military elements still operate with substantial autonomy and impunity. Senior military officers bearing command responsibility for gross human-rights violations were only beginning to face trial in 2002. The police remain unable to assume internal-security duties.

The lack of effective security-sector reform has exacerbated the violence plaguing Indonesia's outer provinces. As well as initiating a democratic transition, Suharto's downfall allowed a major policy change with regard to East Timor, leading indirectly but rapidly to the territory's freedom from Indonesia. Although this successful separation encouraged secessionism in Aceh and Papua, the government in Jakarta will not allow these rebellious provinces more than a form of autonomy that permits a large measure of self-government and substantially greater provincial benefit from the exploitation of local resources. Less extensive autonomy has been granted to other regions as a means of pre-empting secessionist tendencies. At the same time, however, Megawati's administration has allowed the military to pursue a repressive security solution against separatist movements in Aceh and Papua, despite clear evidence that such an approach has proved counter-productive in the past.