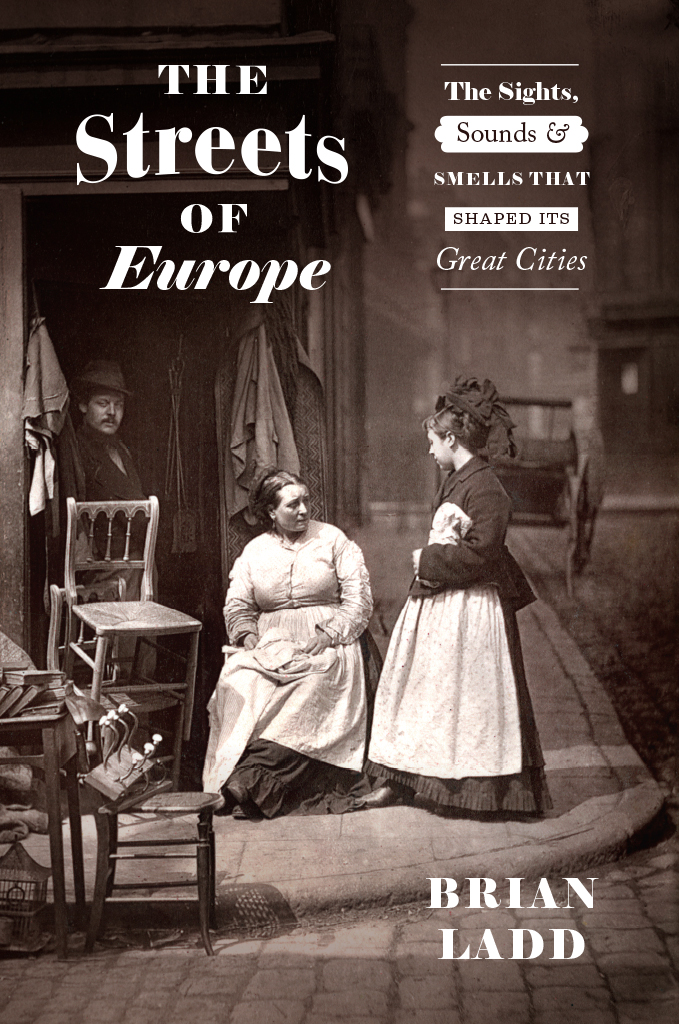

THE STREETS OF EUROPE

THE STREETS OF EUROPE

The Sights, Sounds, and Smells That Shaped Its Great Cities

Brian Ladd

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2020 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2020

Printed in the United States of America

29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-67794-1 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-67813-9 (e-book)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226678139.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Ladd, Brian, 1957 author.

Title: The streets of Europe: the sights, sounds, and smells that shaped its great cities / Brian Ladd.

Description: Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019035376 | ISBN 9780226677941 (cloth) | ISBN 9780226678139 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : StreetsEnglandLondonHistory. | StreetsFranceParisHistory. | StreetsGermanyBerlinHistory. | StreetsAustriaViennaHistory. | StreetsSocial aspectsEuropeHistory. | Sociology, UrbanEuropeHistory.

Classification: LCC HT 153 . L 265 2020 | DDC 307.76094dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019035376

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Contents

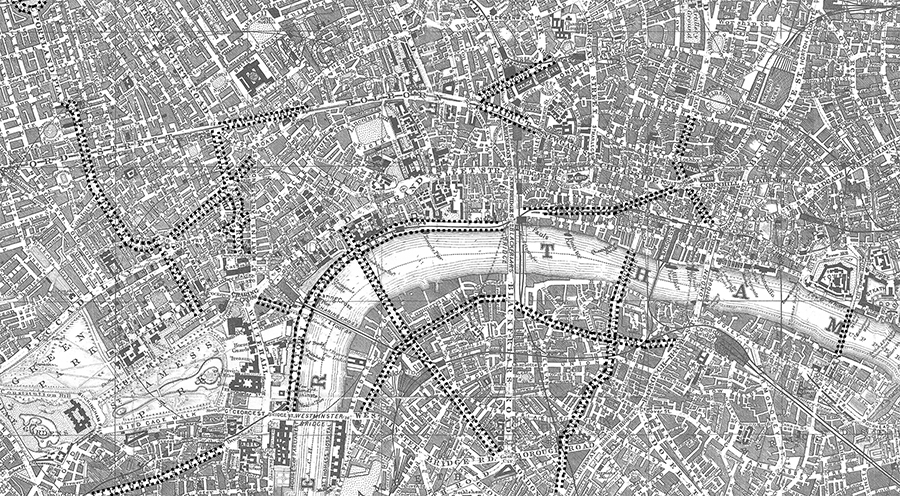

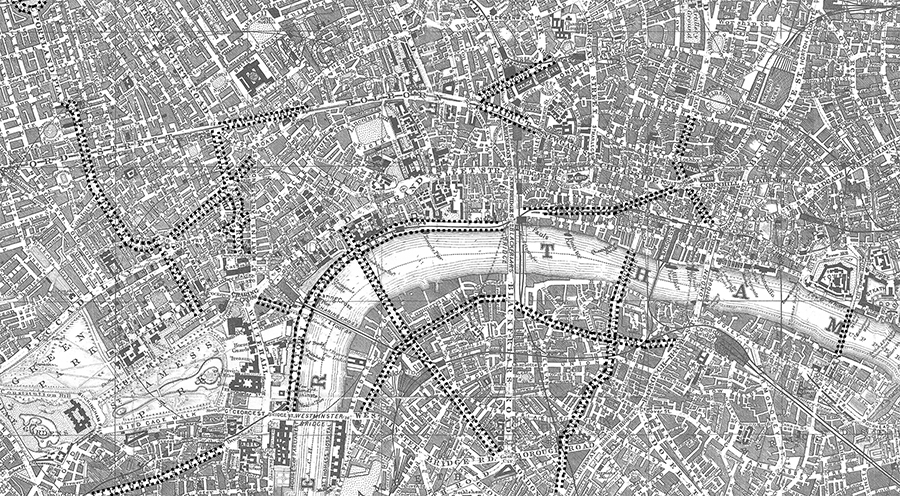

MAP 1. Central London, 1899, with bold dotted lines highlighting new streets built during the nineteenth century.

MAP 2. Central Paris, 1892, highlighting eighteenth-century circuit of Grands Boulevards (dotted lines) and new post-1850 streets (solid lines).

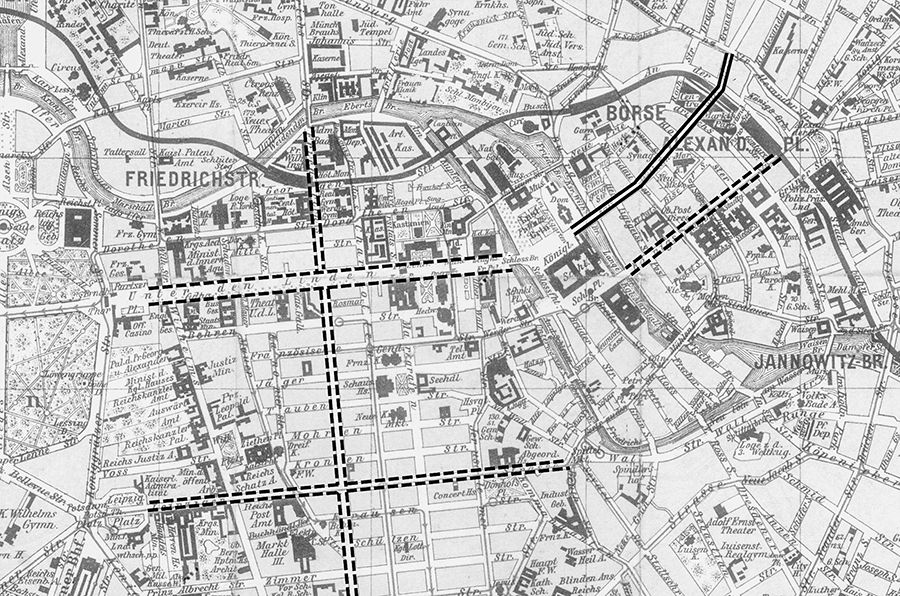

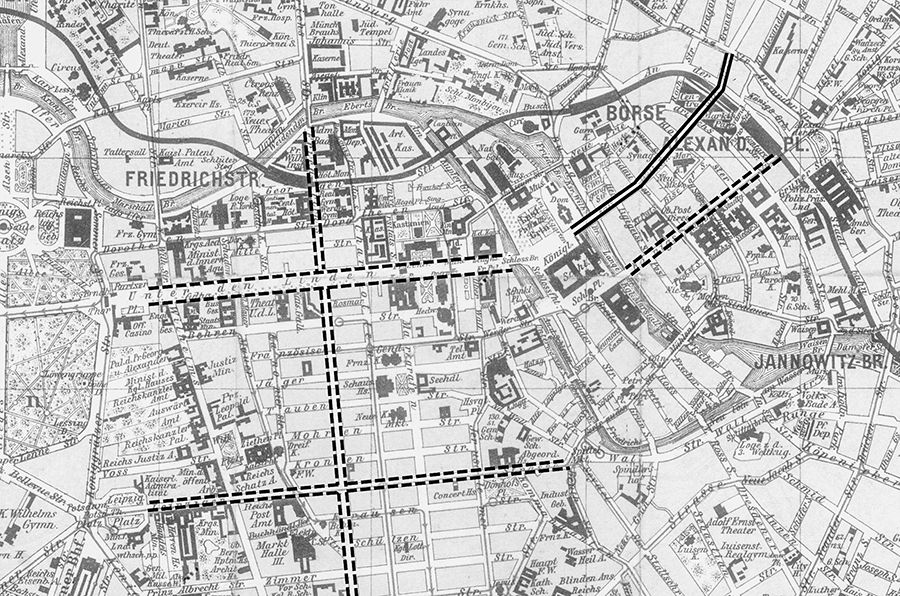

MAP 3. Central Berlin, 1902.

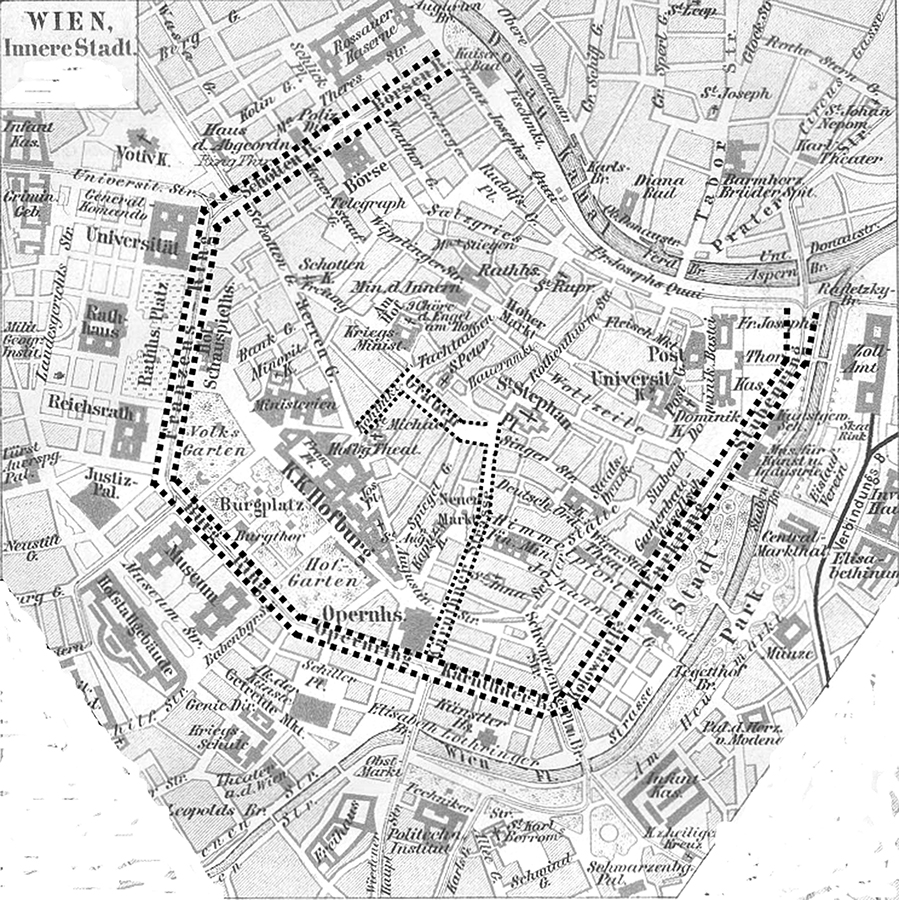

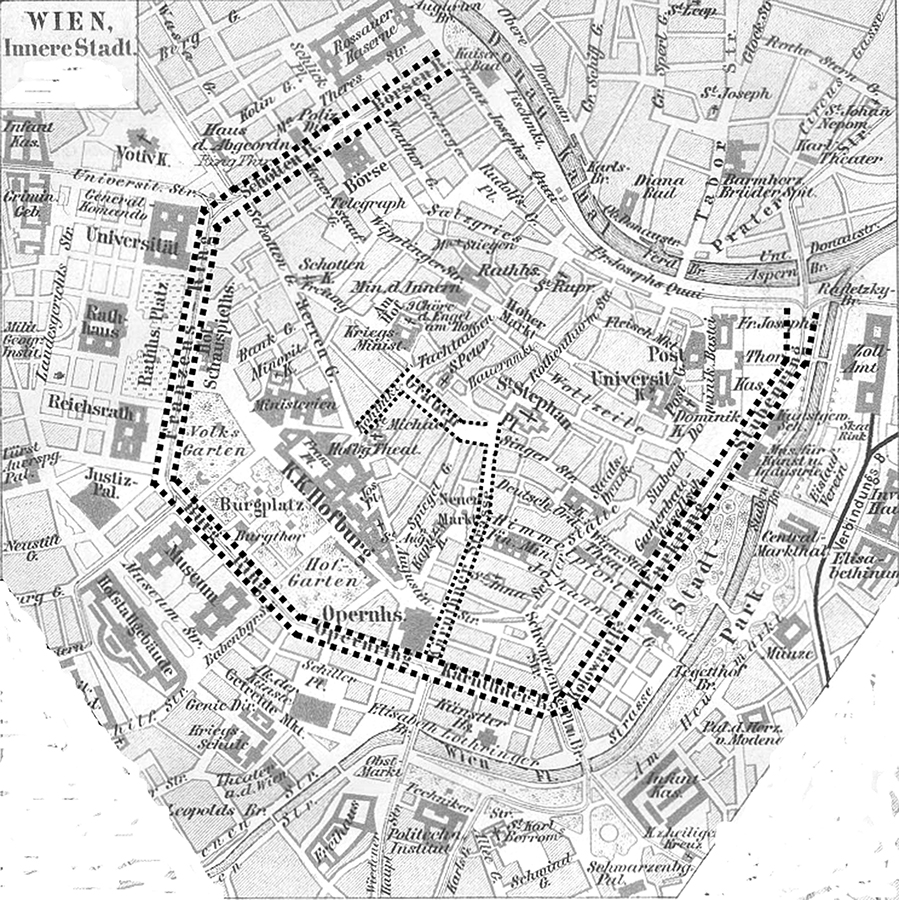

MAP 4. Central Vienna, 1878, with bold dotted lines showing circuit of new Ringstrasse and major inner-city shopping streets: Krtnerstrasse, Graben, and Kohlmarkt.

The Form and Use of City Streets

The twenty-first century is the urban century. For the first time in history, a majority of the worlds population lives in cities, with all the amenities and all the nuisances they have to offer. Life in close proximity to so many strangers demands compromises but also provides opportunities. Despite worries about their growth and crowding, cities may be more appealing than ever before. For ambitious young people in particular, the economic and cultural attractions of city life seem to outweigh the fears of crime, grime, and slime that repelled many of their elders.

Cities are, or can be, the places where everyone coexists, where old hierarchies crumble, and where barriers of ethnicity, class, and gender break down. One of their attractions is the possibility of human contactvisual, verbal, and tactile, especially the serendipitous encounters that happen only in crowds and public places. Theorists of economic development and of psychological well-being argue that opportunities for face-to-face contact are beneficial, and that they can be further enriched by the ethnic diversity of urban populations.

The quintessential place of crowds and strangers, of stimulation and surprises, is the city street, especially in the enclosed form it developed up to the nineteenth century. There has been a recent revival of interest in this kind of street, as cities across the world have proclaimed or pursued a resurgence of street life. Civic leaders hope to recover something that was lost during the twentieth century when street life was deliberately impoverished or abandoned. For much of that century, disgust with streets, if not fear of them, outweighed any lingering affection. Urban development broke radically with tradition, dispersing buildings away from streets and from each other. Advocates of urban revitalization, aghast at the results, believe that old streets can bring new life to cities, and they have sought to revise the historical picture by recalling both the pleasures and the practical advantages of the public street. They offer a useful corrective to older prejudices. The rosy history they tell can, however, be as one-sided as the bleak image they seek to counter, which portrayed streets as filthy and dangerous. Apart, perhaps, from exceptional and fleeting moments of political or religious alchemy, the street has rarely been a place of harmony. Friction and conflict have been more typicaland in fact are essential to productive urban life. To understand the appeal and the value of streets, we need to acknowledge their inherent tension but also to understand how it contributes to their pleasures and benefits.

An old painting or photo or film of a crowded street can appeal to many of us because it seems to promise a thrilling social experience. But a desire to recover the glories of the past also risks ignoring the deep chasm that separates us from it. The resemblance between urban crowds of different eras may be less than meets the eye. Pictures and descriptions of apparently harmonious street scenes from the nineteenth century can be deceiving because they do not reveal that the visible order depended on participants who observed invisible distinctions of deference and subservience, with nearly everyone conforming to more or less clearly defined class and gender roles that constrained their behavior. Some of those roles live on, but most have changed beyond recognition, replaced by other tacit or even unconscious rules that ensure outward harmony in our own streets today. As a result, many of us can be drawn to a charming street because either physical designs or visible authorities keep the poor, the homeless, or the ethnically other at a safe distance. As in the past, for many women a sense of comfort in the streets still depends on obvious or subtle signals that make them feel safe from harassment and sexual violence. In this we find echoes of the nineteenth century: although profound changes in gender roles and womens expectations entail different signals and customs, bold women are once again rewriting codes of public conduct.

We can learn from the urban past only if we remember that our needs have changedin dwelling, working, and shopping. Our expectations, too, are different: for privacy or solitude; for sights and smells we welcome and others that we dont. Across the centuries, we can trace gradual changes in the ways people of different classes and genders used their streets and interacted with, or avoided, their neighbors. It is obvious that people in the twenty-first century can satisfy more of their needs without leaving their homes or coming into direct contact with strangers. A torrent of manifestos at the turn of the new century declared our imminent liberation from space and locality and even materiality. Some of them also predicted the imminent death of city life, reviving an old anti-urban tradition that feeds on fears of crowds and strangers. Of that demise there is little sign, but the use of urban spaceits role in our livescontinues to change.

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).