Introduction

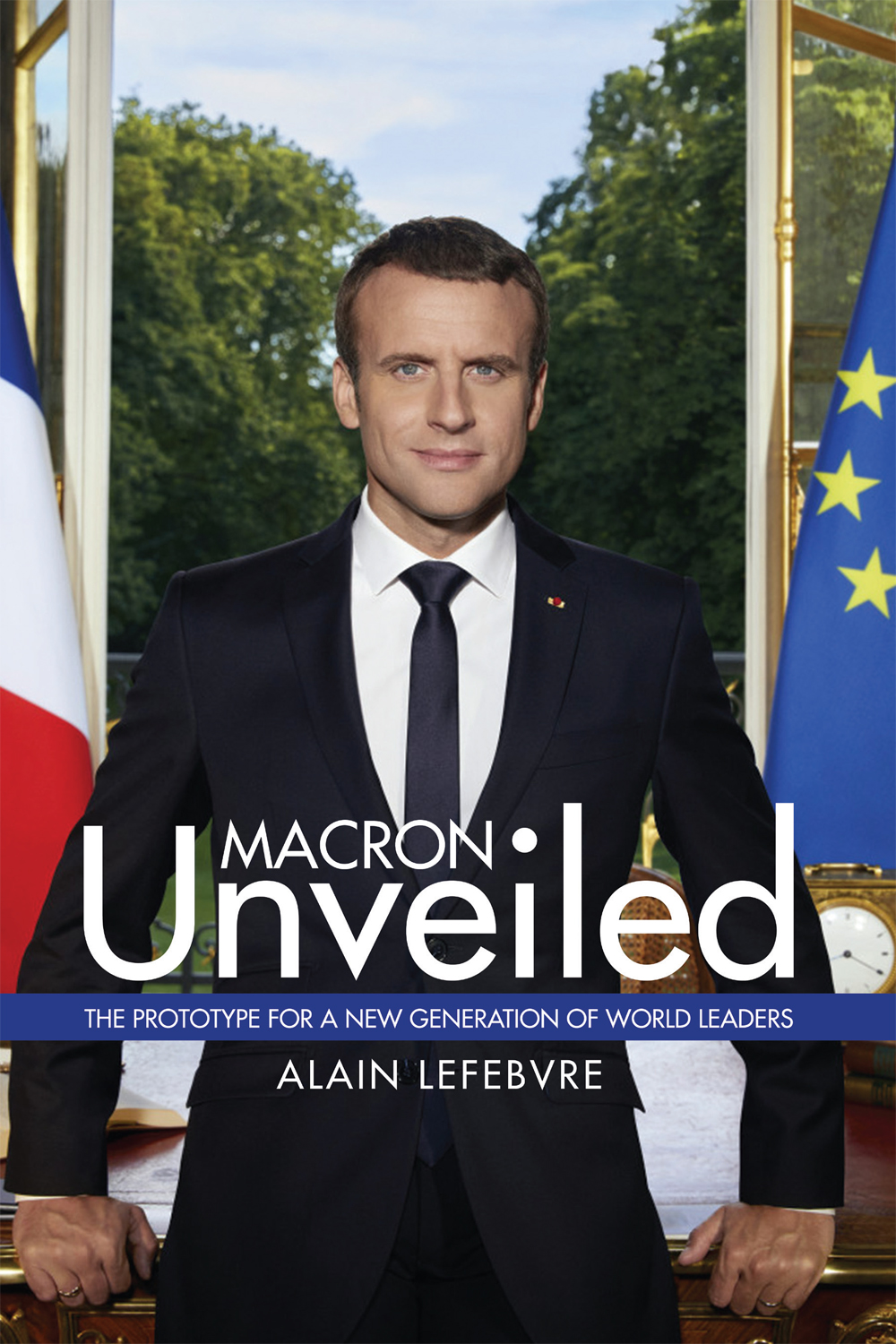

Emmanuel Macron knows that the world of the twenty-first century is changing with unforeseen rapidity. From the start of his presidency, Macrons strategic independence was evident. The first head of state that he invited to France for an official visit was President Putin. And Europe is central to Macrons vision of an effective multilateral world order. In this respect, he exhibits similarities to Charles de Gaulle, who challenged American hegemony within NATO and strived to make France an independent European power. Macron is more diplomatic, more nuanced, and more modern, but like de Gaulle, he aspires to make France an independent, humanist, European power; one that is a global force for good within the limits of its ability and influence, without unrealistic objectives, without overreach, without making the mistake of trying to solve all the worlds problems.

The United States recent ignominious withdrawal from Afghanistan after 20 years and almost $3 trillion in expenditure was a watershed moment in history, one that will not be lost on Emmanuel Macron. The American failure in Afghanistan serves to reinforce the overwhelming lesson of the past 75 years since World War II, that military solutions are rarely if ever a successful long-term answer to political conflicts, even when there is short-term success. The use of military means to make other sovereign regimes, foreign cultures, and different civilizations conform to a particular world view whether under the guise of spreading democracy or dressed up as nation-building or masquerading as a force for common good never was, and never could be justified. Macron knows that too.

Shortly after his election, he took an early and emphatic stand on the U.S.-led offensives against Iraq and Libya, stating that: Democracy is not built from the outside without the support of the people. France did not participate in the war in Iraq, and it was right. And it was wrong to wage war in this way in Libya.

Few would now doubt the wisdom of Macrons position on the conflicts in Iraq and Syria. Democracy may be the most desirable form of government but it cannot be imposed from the outside, let alone by military force. And it is not necessarily practicable or appropriate for every country. The variety and diversity of the worlds cultures, political systems, and civilizations defy ready categorization, let alone simplistic ones. Many political systems and forms of government may not meet our approval. Some are positively distasteful; others egregious; a few iniquitous. And many forms of folly and malevolence masquerade as democracies; while many authoritarian regimes are benign and others far less so. There are no simple solutions. Emmanuel Macron understands that.

After decades of American unilateralism culminating with President Trumps America First mantra, France and Germany, guided by President Macron and Chancellor Merkel respectively, have been active in promoting the return of a multilateral world order, based on a framework of international cooperation underpinned by strong and effective institutions, in which Europe plays a key role. In Macrons vision of a future world order, the best guarantee of global security and prosperity is a multilateral rules-based order, not exclusively a U.S.-led rules based order. For Macron, one consequence of the diminution of the power, prestige, and authority of the United States is the need for a strengthening of international institutions and increased global cooperation. In the new and unfolding world after Afghanistan, American power and influence will remain significant, although not as pervasive or pre-eminent as it has been, while the European Union, Russia, China, and the United Nations Security Council will also be important cornerstones of a multilateral world order. The European Union, China, and Russia are all working, for example, on ways of challenging the primacy of the U.S. dollar as the worlds dominant reserve currency, including, in the cases of China and Russia, on the adoption of new financial instruments and digital currencies.

The recent diplomatic contribution of France in the war-ravaged Middle East, provides another insight into how the future might look when there is a lighter American footprint. As the United States military presence in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria ends or is reduced, diplomacy is returning. The recent Baghdad Conference for Cooperation & Partnership hosted by Iraq which Macron was instrumental in organizing was a remarkable historic victory in itself. America was not invited to the table. The conference brought together friends and foes: Iran and its sometime enemy Saudi Arabia; Qatar and its recent adversaries the UAE, Egypt and Kuwait; as well as Turkey and Jordan. All participants agreed to support Iraq in preserving security, reconstruction, and economic reform and stressed the necessity for regional cooperation in dealing with common challenges. King Abdullah of Jordan noted that Iraq was the priority of all participants. The conference for which Macron can take much credit was a significant step for Iraq towards a post-American era in the region.

Similarly, European Union diplomacy, especially from France and Germany, has been instrumental in maintaining engagement with Iran despite Washingtons vilification of Iran, the painful provocation caused by the unilateral withdrawal of the United States from the nuclear deal, its re-imposition of sanctions, and its assassination of Iranian General Qasem Suleimani. On this issue as well, Macron has placed France at the center of the negotiations. The European efforts are providing a bridge for U.S.-Iranian re-engagement, which may regrettably still come to nothing given the bitterness of some hardliners in the Iranian regime. But the prospect of normalized economic relations with Europe provides an incentive for Iran to commit to some form of reconstituted deal limiting its nuclear weapons aspirations. France is playing an indispensable role.

In relations with China also, Macron has shown pragmatic leadership in contrast to the binary and often antagonistic approach of the United States. Europe has its disputes with China currently reflected in subsisting mutual sanctions but France and Germany in particular are careful to avoid demonizing China. President Macron has warned that ganging up on China would be counterproductive and that it is necessary to find the right way to engage. The ratification of the China-E.U. trade treaty is currently on hold but each is the others largest trading partner and analysts believe that the agreement will eventually come into force. An economic resolution between China and Europe seems more likely than any resolution with America.

When necessary, Macron is realistic and firm with China. He is not afraid to criticize Beijing but he avoids unnecessary confrontation. His forceful response to the constant clamor for action over the treatment of Uighurs in Xinjiang, was icily direct: I am not going to start a war with China on this subject. The Uighur issue is a troubling domestic question, unique to China, that arises inside a sovereign country. Macron knows that there are other ways of attempting to influence Chinas behavior. He also knows that it is a mistake to conflate moral issues with strategic concerns; and that human rights abuses and moral objections to them do not provide a legitimate basis for invasion and war.

In the Indo-Pacific, Macron has grand ambitions. France was once a colonial power in the region and Macron clearly aspires to increase its strategic presence there in the future. In fact, France was the first European Union country to embrace the Indo-Pacific concept in 2018. By 2021, the French Navys operational activity in the region had become particularly intense. Macron wants France to be a mediating, inclusive, and stabilizing Indo-Pacific power, striking an equilibrium between the importance of balancing against China with the need to avoid an escalatory posture towards Beijing; promoting a stable, law-based, multipolar order in the region, and not one solely focused on Americas perceived security interests. Frances Indo-Pacific stretches from Djibouti on the Horn of Africa to Polynesia in the South Pacific and covers a larger area than that over which the United States seeks to extend its influence. Through Frances extensive territorial presence, its growing naval projection capabilities, and its active diplomatic engagement, Macron seeks to make France a committed regional actor and a moderating force that serves as a bridge to Europe.