Copyright 2007 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

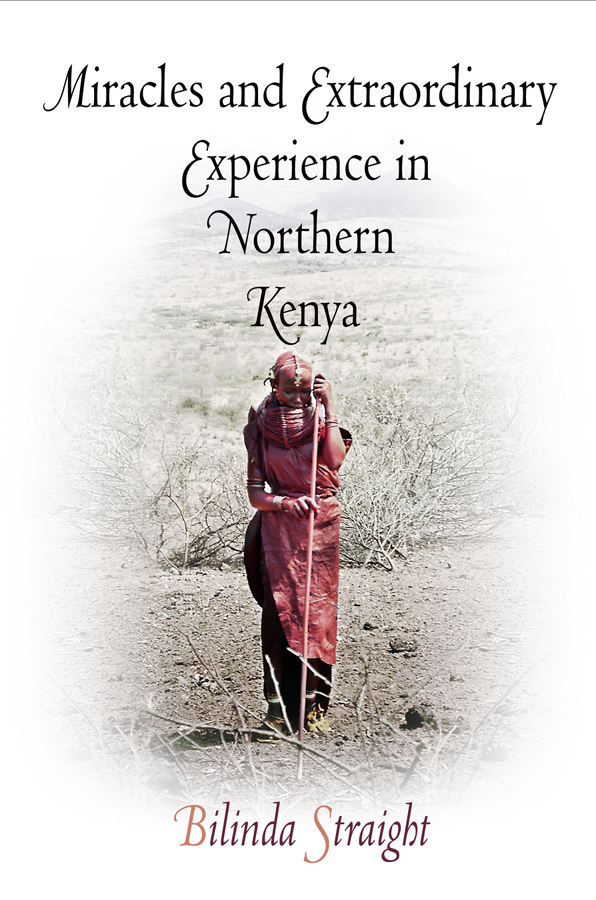

Straight, Bilinda, 1964-

Miracles and extraordinary experience in northern Kenya / Bilinda Straight.

p cm.(Contemporary ethnography)

ISBN-13: 978-0-8122-3964-5 (alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-8122-3964-4 (alk. paper)

Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index.

1. Samburu (African people)Religion. 2. MiraclesKenyaSamburu District.

3. DeathReligious aspects. 4. Resurrection. I. Title. II. Series

BL2480.S235 S73 2007

299.6'85 22dc22

2006042182

For Paul Adler, who put philosophy and poetry into the mind of a ten-year-old, Homeric Greek into the hands of a fifteen-year-old, and the entire world of being into the heart of the child who became a woman who became a lifelong friend.

And in Memory of Roy Rappaport, who inspired me from the very beginning of graduate school, told me what he thought, taught me that anthropology could ask the hard, human questions, and encouraged me with wonderful earnestness and kindness. Kind words go a long way.

Authors Note

We cannot begin with complete doubt. We must begin with all of the prejudices which we actually have when we enter upon the study of philosophy.

Peirce (1958: 40)

What you are about to read is an extended meditation on human experience that is simultaneously philosophical and ethnographic. I wrote most of this books early chapter drafts during a second extended (one-year) field stay in 20012002. At that time, in the midst of partaking of Samburu experiences, I found myself meeting Samburu philosophical reflections with my own. And I returned, in my mind, to my earlier fieldwork (two years, from 1992 to 1994), when I first became overwhelmed by the daily grittiness, joys, and profound sufferings of others. Thus, those earlier experiences were seeping into these later ones, and my earlier thoughts, readings, and writings were as well. My first response in 2001, then, to being utterly surrounded and profoundlyas in, at the core of my beingaffected by my Samburu friends way of being in the world, was to return to my 1993 musings on magical realism and a dream:

I first discovered Borges in Kenya in 1993. In The Aleph Borges compressed the universe into a single point; in The Book of Sand he pressed infinity between the pages of an ancient book. In The Writing of the God he summed up the universe in forty syllables.

I understood these parables in a particular way because at the age of sixteen I had an oft-recurring dream in which the universe revealed itself to me. Omniscient, omnipresent, it told me everything at once. Afraid that I would lose the revelation upon waking, I had repeated the secret over and over, but all of a sudden it had gotten away before Id realized. At first, it seemed retrievable, like it was on the tip of my tongue, as if I could reconjure it with a word. But no, it had slipped away like a living thing, leaving just some fantastic feeling in its place.

Then, much later, the universe returned, this time in a dream of my own passing. I dreamed me in several places and timesone in the Middle Agesand the near and distant in time and place converged in a single death. I dreamed the pain, the receding vision, the voices disappearing around me. And then, I dreamed myself moving toward a total becoming that I knew was total completion. I felt myself dissolving into each individual atom simultaneously, infinite particles carried somewhere, joining with every other in the universe. And in that joining I awoke, knowing that in that death, I would remember nothing and everything.

What I understood by 1993 was that, for my friends in the lowlands in particular, life was often experienced as being at risk of slipping away, and an understanding of the relationship between the living and the dead was at once necessary and occasionally horrifying. At the same time, I recognized what my dreams were telling me: that writing about Samburu experiences, or anyones experiences including my own, was also about a slipping away, about conjuring something that had just been on the tip of my tongue. So I wrote most of this book in the field, putting stories in as soon as they happened, letting myself be driven along by the many points of wisdom of my Samburu friends as they revealed them to me. And this animal of a book grew. As soon as I started it, though, I knew that I could not separate myself from their experiences, nor could I separate my thoughts from theirs. My thought as a scholar began to mature during those first two years of fieldwork, and there was no going back to a time when I could distinguish my Euro-American ideas from those of my Samburu friends. Do we ever start fieldwork with a clean philosophical and political slate? I do not believe so. What I have written here is a textual culmination of a joint project of illumination.

And that means I have many people to thank, beginning with my Samburu friends. I cannot thank you all enough, and I cannot name every one of you as individuals. I am indebted to everyone in Samburu District I have known from 1992 to the present. In particular, I would like to thank Musa Letuaa for being more than a friend and always my philosophical challenger. I simply cannot praise you enough, Musa. Our 2001 reunion embrace expressed our friendship better than these words, but these words are for you anyway: Thank you. I would also like to thank Timothy Loishopoko and Augustine Lengerded for likewise extending me very warm friendships and for pushing my understandings of Samburu philosophy and experience in profound ways. In addition, I am grateful to Joy, John Letiwa, Jonathan and Paul Lepoora, and John Lesepe for research assistance. I also cherish the memories of Lydia Lemelita, my first research assistant, and Damaris Lalampaa, my research assistant and friend, whose cheerful personality and sweet generosity I shall always miss. Also in Samburu District I would like to thank Adamson Lanyasunya for transcription assistance in the 1990s and for the many kinds of hospitality and assistance he has extended since then. In addition, Barnabas Lanyasunya has been wonderful (as has Lengerded) in transcribing interviews, and Sammy Letoole has just been a joy to interact with.

My hosts also deserve appreciation, and thus my thanks go out to Lekeren (in the highlands) and the members of his family who have made me feel welcome since 2001, including his wives Meruni and Alenii, his sister Yaniko, who has also been very helpful as a research assistant since 2004, and his brother Stimu. As Lekeren has often said, we are one family. My gratitude also goes to Lkonten Lemarash (in the lowlands) and his familymy familywho adopted me as their own in 1992 and have kept me ever since. I cannot name you all, but I want to thank Naliapu (oto Ropili) Lemarash for her kindness and friendship, including taking care of me and my sons when we were ill: I have felt like a daughter, and I will always remember that night you cared for my son Jen when we were both very concerned and help was a full day away. I want to also thank Namaita (oto Tampia) Lemarash for hospitality and humor, Naismari Lemarash for putting up with my video camera, Tampia and Narimu for being sweet younger sisters to me, Ropili for lasting friendship with Jesse, Kokoso for being fun, funny, and always trying to be helpful, and yes, Nolwara, I thank you for being the incredible, warm friend that you are. I love you. I would like also to name Lekanapan and his wife for extraordinary hospitality and friendship over the years, and the same goes for Lopeleu Lekupano and his wives. And a special thanks to Lopeleus father for being a philosopher king. The Lesirayon family also deserve thanks, and Mepukori Lesirayon deserves particular gratitude for carrying the log that became my big calabash that time. A huge thank-you goes to Josephine Nokorod for caring for and loving my children from 1992 to the present and keeping the house together while I did research. In short, I thank you all, including all of you I cannot take more space to name. Then I want to thank Father Francis Viotto for kindly storing my research vehicle, and Father Marco Prastaro for warm conversations and many kindnesses. Finally, although by no means last in my thoughts, I would like to express my gratitude to Carolyn and Lolkitari Lesorogol for endless hospitality and logistical help over the years, including overseeing the building of a house! My thanks to Carolyn as well for a friendship that has meant a lot and for support as a colleague.