Dialogue with Europe, Dialogue with the Past

Colonial Nahua and Quechua Elites in Their Own Words

Edited by

Justyna Olko, John Sullivan, and Jan Szemiski

University Press of Colorado

Louisville

2018 by University Press of Colorado

Published by University Press of Colorado

245 Century Circle, Suite 202

Louisville, Colorado 80027

All rights reserved

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of

the Association of University Presses.

The University Press of Colorado is a cooperative publishing enterprise supported, in part, by Adams State University, Colorado State University, Fort Lewis College, Metropolitan State University of Denver, Regis University, University of Colorado, University of Northern Colorado, Utah State University, and Western State Colorado University.

ISBN: 978-1-60732-832-2 (cloth)

ISBN: 978-1-60732-833-9 (pbk.)

ISBN: 978-1-60732-834-6 (ebook)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5876/9781607328346

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Olko, Justyna, editor. | Sullivan, John, 1956 editor. | Szeminski, Jan, editor.

Title: Dialogue with Europe, dialogue with the past : colonial Nahua and Quechua elites in their own words / edited by Justyna Olko, John Sullivan and Jan Szeminski.

Description: Boulder : University Press of Colorado, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018045831| ISBN 9781607328322 (cloth) | ISBN 9781607328339 (pbk.)

| ISBN 9781607328346 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: MexicoHistorySpanish colony, 15401810Sources. | PeruHistoryConquest, 15221548Sources. | NahuasMexicoHistorySources. | Quechua IndiansPeruHistorySources. | Nahuatl languageTexts. | Quechua languageTexts. | Spanish languageTexts. | Elite (Social sciences)MexicoHistory. | Elite (Social sciences)PeruHistory.

Classification: LCC F1219 .D4595 2018 | DDC 972/.02dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018045831

The University Press of Colorado gratefully acknowledges the generous support of the University of Warsaw toward the publication of this book.

The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Research Council under the European Unions Seventh Framework Program (FP7/20072013)/ERC grant agreement no. 312795.

Cover photograph: Contemporary ritual offering on the floor of the colonial church in Huahquechula (the former Nahua state of Cuauhquechollan), Puebla, Justyna Olko.

In loving memory of Jim Lockhart (19332014)

Contents

Justyna Olko and Jan Szemiski

Justyna Olko and Jan Szemiski

Legal Proceedings

Maria Castaeda de la Paz

Julia Madajczak

Agnieszka Brylak

Agnieszka Brylak

Agnieszka Brylak

Agnieszka Brylak

Agnieszka Brylak

Justyna Olko and John Sullivan

Justyna Olko

John Sullivan

Justyna Olko and John Sullivan

Wills

Justyna Olko

Agnieszka Brylak

Justyna Olko

Patrycja Przdka-Giersz, Jan Szemiski, and John Sullivan

Patrycja Przdka-Giersz, Jan Szemiski, and John Sullivan

Patrycja Przdka-Giersz, Jan Szemiski, and John Sullivan

John Sullivan

Julia Madajczak

Patrycja Przdka-Giersz, Jan Szemiski, and John Sullivan

Justyna Olko

Petitions and Letters

Julia Madajczak, Jan Szemiski, and John Sullivan

Julia Madajczak, Jan Szemiski, and John Sullivan

Anastasia Kalyuta

Julia Madajczak, Jan Szemiski, and John Sullivan

Justyna Olko

Agnieszka Brylak

Agnieszka Brylak

John Sullivan

Justyna Olko

Accounts and Ecclesiastical Writing

Katarzyna Granicka

Agnieszka Brylak

Jan Szemiski

Gregory Haimovich

Jan Szemiski

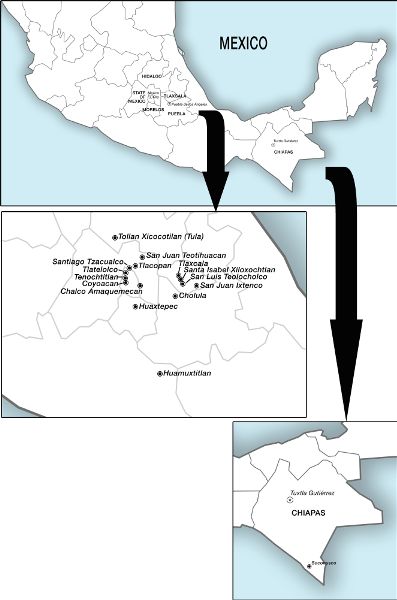

Locations in Mexico discussed in the text

Locations in South America discussed in the text

Justyna Olko and Jan Szemiski

Simultaneously subjects and officials of the Crown, it was they who truly carried out the daily governance of the entire Amerindian population where it survived in New Spain and most parts of the Viceroyalty of Peru. Without the service and collaboration of these members of the dynasties of former kings, lords, and other indigenous leaders, Spanish administrators, and conquerors, who had neither the knowledge nor the ability to govern a local populationinitially of tens of millions but crashing later to only several millionwould not have succeeded. They were too few. However, it is clear from indigenous documents that native elites looked at this process, as well as their position, roles, goals, and advantages in it, in a much different way than was perceived by the Spaniards and, later, the historians who relied exclusively on Spanish sources.

These processes were obviously also directly influenced by the Crowns strategies and the attitudes of its representatives. The conquerors wanted native Americans alive and economically productive. In Haiti (Hispaniola, Espaola, Santo Domingo), the Spaniards had already discovered that they desperately needed the cooperation of the local leaders, called caciques in the Taino language. Without them they would not get food, much less gold, women, or other precious goods. This initial experience must have had lasting impact, because the word cacique became the general name for all indigenous leaders in the Spanish empire, from California and Florida to Chile and Buenos Aires, from Navajos and Seminoles in the north to Mapuches and Tehuelches in the south. Indigenous elites, however, were not composed of only caciques and their families. Administration in native states and chiefdoms was much more complex because local rulers relied on various kinds of functionaries to administer their own possessions, organize and supervise the work of their subjects, and collect their taxes. Thus all local states in Mexico and Guatemala had their calpixqueh (administrators) and scribes, while all local officials in the Inca empire had their khipu kamayuqs, specialists in knot notations for keeping track of statistics, calendars, properties, and histories. These are not exhaustive: native elites needed many more types of specialists, including artisans, agronomists, and engineers. On the other hand, the kings of Castile and Leon, both of whose kingdoms rather than Spain as a whole shared rights to the American possessions, recognized Amerindian elites as nobility. This was extremely important to native noblemen because it meant that, solely because of their birth status, they were exempt from head tax and could not be obliged to participate in forced labor, as were all other indigenous subjects. For this reason, the numbers of local nobility quickly swelled. Everyone sought to be included, just as did those Spaniards in America who cited Asturias, inhabited exclusively by