Contents

Guide

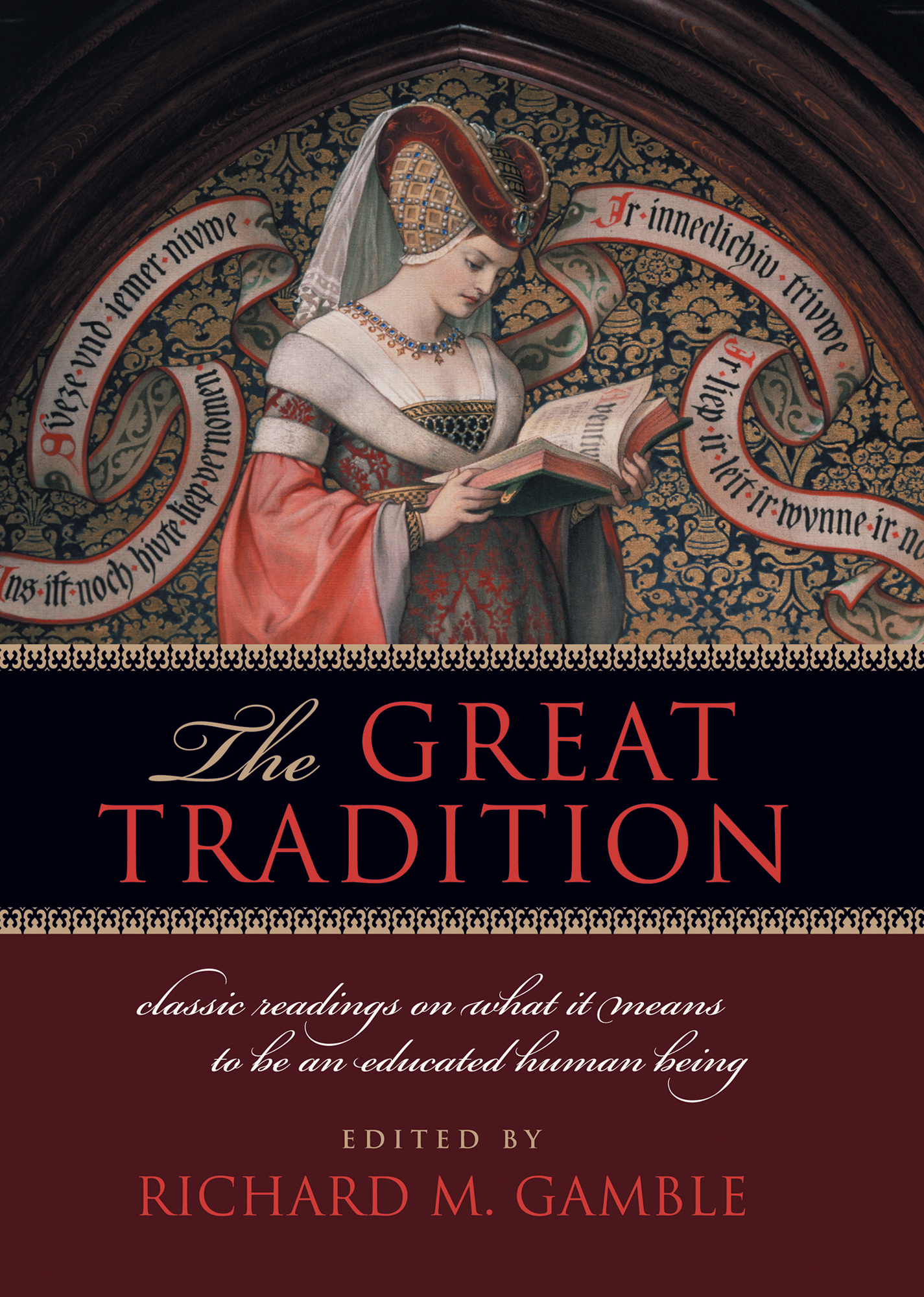

The Great Tradition

Classic readings on what it means to be an educated human being

Edited by Richard M. Gamble

To Thomas J. St. Antoine,

a teacher with the courage to make students unfit

for the modern world

Acknowledgments

C redit for this anthology belongs to the authors included herein. My task as compiler and editor has been merely to reap a harvest that others have sown and tended over millennia. I can offer no better thanks to the faithful teachers within the Great Tradition than to pass on their legacy to others.

This project began while I was on sabbatical leave from Palm Beach Atlantic University in the spring of 2003. The board of trustees and then-president Paul Corts awarded me the inestimable privilege of time away from the daily duties of teaching simply to think, to read, and to begin piecing together what I only vaguely knew as the Great Tradition. A generous grant from the H. B. Earhart Foundation enabled me to spend my sabbatical at Cambridge University. I am indebted to several friends and institutions in Cambridge who welcomed me into their venerable academic community that semester. Bruce Winter, at that time warden of Tyndall House, provided me with an appointment as reader, a comfortable home, a quiet library, and the companionship of an international group of scholars. His generous assistance also opened the way to my appointment as visiting scholar at St. Edmunds College. There is no more hospitable college in all of Cambridge. Also, two dear friends, Chad and Emily Van Dixhoorn, always made room for me in their growing family.

At ISI Books, editor in chief Jeremy Beer guided this project from the time it was barely a mental sketch. His enthusiasm, good humor, and attention to detail make it an ongoing privilege to work with him. Managing editor Jennifer Connolly hunted down copyright holders and brought order and coherence to an unwieldy mass of material. In every facet of its operations, ISI Books blends professionalism and informality in a way that makes an author feel at home.

If this anthology has any single point of origin, it is in the vibrant conversation that took place among the faculty and students in the honors program at Palm Beach Atlantic University. Together, in rare camaraderie, my former colleagues and I struggled to reassemble the liberal arts tradition, to teach ourselves in a comprehensive and systematic way what many of us had been taught only in fragments. The simple joy of discovery sustained us through years of hard work. Our students patiently endured our earnest attempts to teach ourselves in the guise of teaching them. But it was the students, of course, who gave it all meaning and enduring significance. By singling out the programs current director, Tom St. Antoine, to whom this volume is dedicated, I wish to express my indebtedness to all my former colleagues and students. May they continue to give what they have received.

H ILLSDALE , M ICHIGAN

J UNE 2007

Introduction

E velyn Waughs gently satirical Scott-Kings Modern Europe follows the declining career of a classics teacher at Granchester, a fictional English public school. Granchester is entirely respectable but in need of a bit of modernizing, at least in the opinion of its pragmatic headmaster, who is attuned to consumer demands. The story ends with a poignant conversation between Scott-King and the headmaster:

You know, [the headmaster] said, we are starting this year with fifteen fewer classical specialists than we had last term?

I thought that would be about the number.

As you know Im an old Greats man myself. I deplore it as much as you do. But what are we to do? Parents are not interested in producing the complete man any more. They want to qualify their boys for jobs in the modern world. You can hardly blame them, can you?

Oh yes, said Scott-King. I can and do.

I always say you are a much more important man here than I am. One couldnt conceive of Granchester without Scott-King. But has it ever occurred to you that a time may come when there will be no more classical boys at all?

Oh yes. Often.

What I was going to suggest wasI wonder if you will consider taking some other subject as well as the classics? History, for example, preferably economic history?

No, headmaster.

But, you know, there may be something of a crisis ahead.

Yes, headmaster.

Then what do you intend to do?

If you approve, headmaster, I will stay as I am here as long as any boy wants to read the classics. I think it would be very wicked indeed to do anything to fit a boy for the modern world.

Its a short-sighted view, Scott-King.

There, headmaster, with all respect, I differ from you profoundly. I think it the most long-sighted view it is possible to take.

And there ends the story of Scott-Kings misadventures in the modern world. Any teacher who has endured a similar conversation sympathizes instinctively with poor Scott-King. His dignified but stubborn resistance to the wickedness of making students fit for the modern world speaks to the heart of teachers who, like Scott-King, take the long view. It is to these teachers, thenand to like-minded students, parents, and administratorsthat this anthology of classic writings on education is addressed. This collection from what has been called the Great Tradition is intended to supply an arsenal of the liberal arts for those who would wage warcovertly or openlyon the side of an education rooted in the classical and Christian heritage. It will, I hope, inspire modern misfits who seek to initiate themselves and their students into an ancient way of teaching and learning much larger than themselves, and who recognize that their task is chiefly formative rather than instrumental. Readers looking for up-to-the-minute advice about innovative teaching methods and classroom technology, or about how to prepare students for the real world and tomorrows top-ten careers, will be gravely disappointed.

By design, this anthology offers nothing new. As C. S. Lewis remarked in his preface to The Problem of Pain, any originality here is unintentional. Furthermore, this anthology is meant neither to be a documentary history of education in the West nor a comprehensive survey of competing philosophies of education. It excludes utilitarians, romantics, and progressives; there is nothing here by John Locke, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, or John Dewey. Instead, it follows the trail of an older, more noble, and continual conversation about what it means to be a truly educated human being.

More than two hundred years ago, the utilitarians disconnected themselves from liberal education and the Great Tradition, redefining and redirecting the useful away from that which forms the complete man, and toward that which primarily promotes mans material well-being. Of course, education has always aimed to be useful. The question has been, and continues to be, useful to what end? The modern age, often with good intentions, has defined educational usefulness as that which leads to material results that can be weighed and measured and counted. Thus, it is no surprise that it has been darkened by the spiritual eclipse that Saint Augustine warned us against so long ago in his Confessions. The Great Tradition, in contrast, anchored in the classical and Christian humanism of liberal education, has taken the broader view that what is useful is that which helps men and women to flourish in nonmaterial ways as wellin other words, that which helps them to be happy. Indeed, what the Great Tradition has meant by the words humanism, liberal, and education will emerge from the full contextspanning a breathtaking twenty-four centuriesof the remarkably intelligible, unified, and coherent conversation that unfolds in these pages.