CONTENTS

The fundamental urge to alter our consciousness in significant but controllable ways is, it seems, part of our hard-wiring. Very few people live their lives without using some kind of mind-altering substance, be it a cup of coffee, a glass of wine, sleeping pills, cigarettes or betel. The abundance of intoxicants and the myriad ways in which they are woven into the fabric of cultures around the world have left an extremely rich visual and material record, which this book explores. Moreover, drugs have significantly influenced social and cultural movements, defining entire subcultures from coffeehouses and opium dens to modern-day raves. Mind-altering substances answer the deep desire need, even we have to enhance and extend our ordinary experience of life.

As a habit, taking drugs seems directly related to our core interest in experimentation: the indulgence of our inclination to wonder What if?. Accordingly, scientific enquiry into this aspect of human experience has progressively deepened and broadened in modern times. Since the eighteenth century, the development of new drugs has played out against a backdrop of pharmacological investigation and application, with traditional substances derived from plants and herbs augmented and then supplanted by synthetic chemicals. Though inevitably more subjective, the actual experience of drug consumption has also become an increasing focus of enquiry, frequently through self-experiment. Here the approach of science has gone hand in hand with the practices of art to explore the impact of drugs on creativity. More recently, in a century when the social impact of drug consumption has emerged as an ever-more-threatening social menace, science has also been called upon for guidance in tackling the problem of addiction.

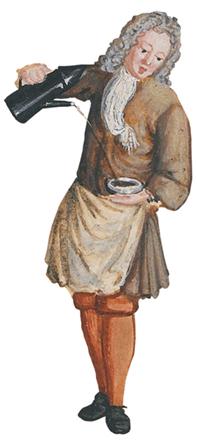

A waiter pours a drink for a customer in a painting of an eighteenth-century London coffee house (detail). ( The Trustees of the British Museum)

Ceremonial drinking of kava in the Friendly Islands (Tonga), engraving by W. Sharp after John Webber (detail). (Wellcome Library, London)

A Mandarin sits on a mat, smoking a long opium pipe, in a coloured aquatint by Swiss artist Sigismond Himely, c. 1820. (Wellcome Library, London)

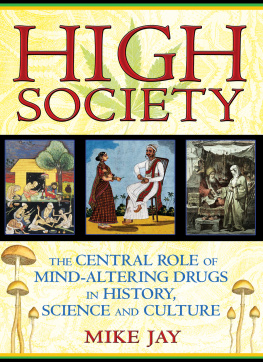

High Society is an intriguingly multi-layered account of humanitys long and elaborate dance with mind-altering drugs. It was written as an extension of Mike Jays advisory and curatorial work on an exhibition of the same name presented at Wellcome Collection, London. Wellcome Collection was not conceived as a conventional venue for the dissemination and popularization of scientific knowledge. Instead its approach has been to think in public out loud, as it were about medical science and its connections with art and the rest of life. The subject of drugs, with its rich history of scientific experimentation, literary and artistic inspiration, economic opportunity, societally encoded behaviour and fundamental biological effects, is an ideal focus for an institution dedicated to investigating science as a vibrant part of culture.

Ken Arnold

Head of Public Programmes, Wellcome Collection, London

Illustration of a cannabis plant from De historia stirpivm commentarii insignes by the Bavarian physician Leonhart Fuchs (1542). (Wellcome Library, London)

Every society on earth is a high society. As the sun rises in the east, caffeine is infused and sipped across China in countless forms of dried, smoked and fermented tea. From the archipelagos of Indonesia and New Guinea through Thailand, Burma and India, a hundred million chewers of betel prepare their quids of areca nut, pepper leaf and caustic lime ash, press it between their teeth and expectorate the days first mouthful of crimson saliva. Across the cities of Thailand, Korea and China, potent and illicit preparations such as yaaba, home-cooked amphetamine pills swallowed or smoked, propel a young generation through the double working shifts of economic boomtime, or burn up the empty hours of unemployment, before igniting the clubs and bars of the urban nightscape.

As the sun tracks across towards the afternoon, the rooftop terraces of Yemens medieval mud-brick cities fill with men gathering to converse and chew khat through the scorching heat of the day. Across the concrete jungles of the Middle East, millions without the means for a midday meal make do with a heap of sugar stirred into a small cup of strong black tea. As the working day in Europe draws to a close, the traffic through the bars of the city squares begins to pick up, and high-denomination euro notes are surreptitiously exchanged for wraps of cocaine and ecstasy. In the cities of West Africa, the highlife clubs are thick with cannabis smoke, while in the forests initiates of the Bwiti religion sweat their way through their three-day intoxication by the hallucinogenic root iboga, during which they see the visions that will guide them through the passage to adulthood.

When daylight reaches the western hemisphere, it illuminates the broadest spectrum of drug cultures on the planet. Across North Americas cities, the sidewalks throng with office workers clutching lattes and espressos, while giant trucks thunder down interstate highways delivering tobacco and alcohol on a scale now rivalled by the industrial marijuana plantations concealed in giant polytunnels and warehouses among the forest tracts of California and Canada. Further south, the Huichol people of Mexico, despite the mesh fences and enclosures spreading across their ancient hunting grounds, still make their desert pilgrimage to harvest peyote cactus for their rituals, while street children in the barrios of Colombia and Brazil stupefy themselves with petrol-soaked cocaine residue and aerosol sprays. And in the Amazon, dozens of tribes, as they have since time immemorial, squat around fires powdering, toasting and brewing the seeds, roots and leaves of the worlds most diverse mind-altering flora.

Finally the sun sets across the islands of the south Pacific, the most remote outposts of humanity. Here, almost all the drugs consumed by the rest of the world remain unknown: even alcohol and tobacco are costly imports, rare outside the urban centres. But from the middle of the afternoon, the men have been drifting in from their gardens and plantations to grate, chew and soak kava root for their evening brew. As the sun sets, they congregate in huts to drink it from coconut shells and share some whispered conversation, or squat alone on the beach to listen to its voice in the surf, as the sunset fades to darkness.

Drug cultures are endlessly varied, but drugs in general are more or less ubiquitous among our species. The celebrated list of human universals compiled by the anthropologist Donald E. Brown includes mood- or consciousness-altering techniques and/or substances as one of the essential components of human culture, along with music, conflict resolution, language and play. But there is little consensus regarding the origins of this universal impulse, which essential human traits it serves and how far back into our past its roots extend. Some have posited a primordial moment of discovery when proto-humans first encountered plants that expanded their minds to generate new forms of thought and language. Others have argued that such a moment may be encoded in our shared origin myths, perhaps in stories of a fruit that bestowed the knowledge of good and evil. Nevertheless, it seems that the discovery of intoxicants is a drama in which even the remote human past is a very recent episode. The plants that contain these substances evolved alongside our animal antecedents, and many developed such chemicals because of their physiological effects on creatures like ourselves. We were taking drugs long before we were human.

Next page