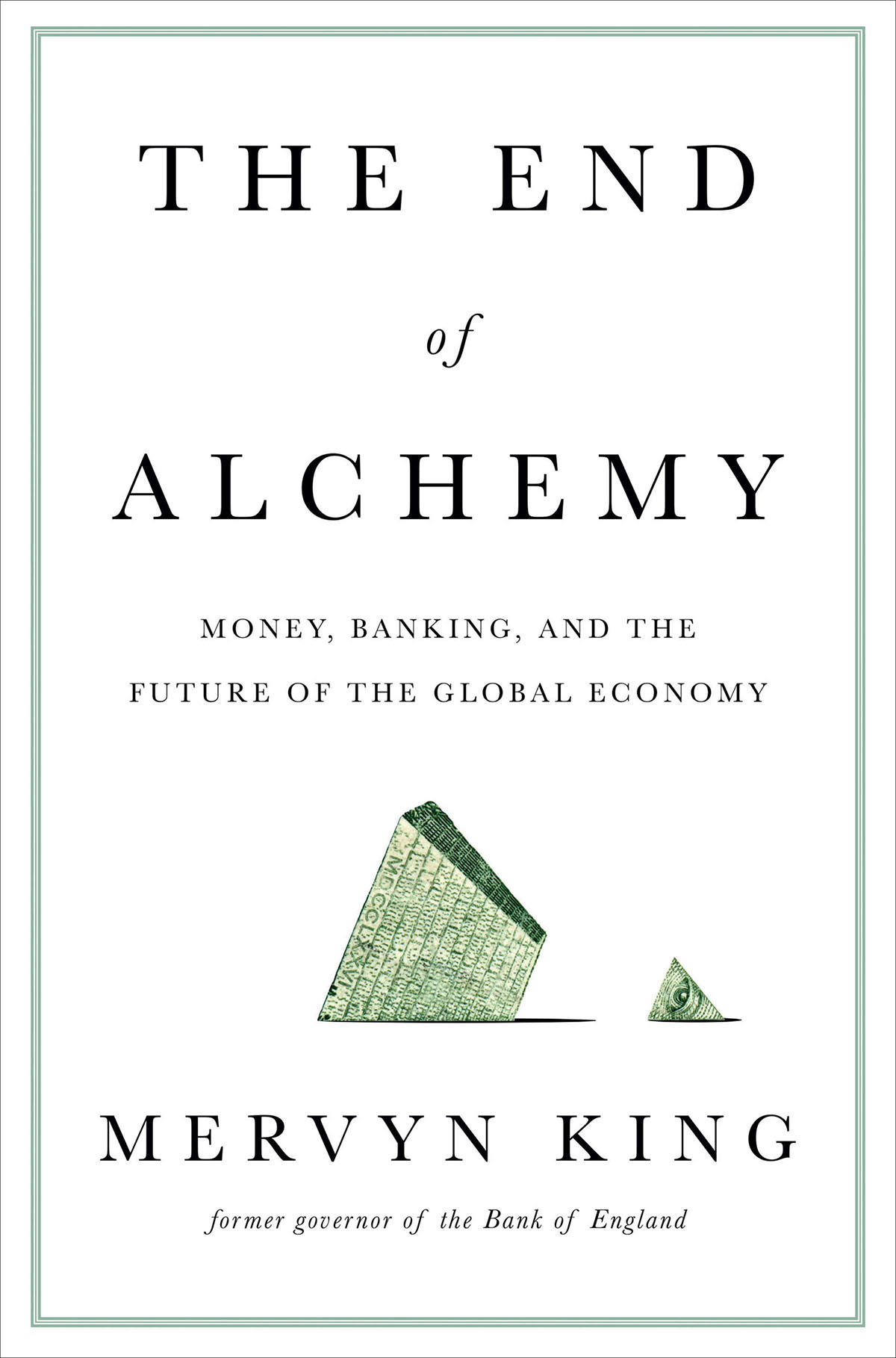

THE END OF

ALCHEMY

Money, Banking, and the Future

of the Global Economy

MERVYN KING

W. W. Norton & Company

Independent Publishers Since 1923

New York London

Copyright 2016 by Mervyn King

All rights reserved

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce selections from

this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton Company, Inc.,

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please

contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com

or 800-233-4830

Production manager: Beth Steidle

ISBN 978-0-393-24702-2

ISBN 978-0-393-24703-9 (e-book)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.,

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.,

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

FOR

Otto, Alexander, Livia and Sofie

The endless cycle of idea and action,

Endless invention, endless experiment,

Brings knowledge of motion, but not of stillness;

Knowledge of speech, but not of silence;

Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge?

Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?

T.S. Eliot, The Rock, 1934

My biggest debt of gratitude is to the team with which I worked in the Bank of England for twenty-two years. When I arrived in the Bank in 1991 to become its Chief Economist, I soon realised how lucky I was. I was surrounded by a group of extraordinarily bright young economists who worked together as a team. Over the years, the Bank has managed to recruit exceptionally congenial as well as talented people. Without such committed staff, none of the achievements of the past twenty years during which the Bank of England has changed from an institution operating in the shadows and behind the scenes to an independent central bank wielding enormous power would have been possible. From my arrival on 1 March 1991, I was totally absorbed in a turbulent, yet ultimately constructive period for economic policy in the United Kingdom. Most of that period was spent in the magnificent Herbert Baker building, which fronts Threadneedle Street, with many weekends spent in international meetings in a range of windowless rooms from Basel to New York and Frankfurt to Washington. On the day of my departure on 30 June 2013, which coincided with the annual Governors Day party for Bank staff and their families at the Roehampton sports ground, I knew that I was leaving one family to return to my own. The warmth of our send-off was reciprocated.

All of my colleagues over the years deserve thanks for making my job much easier than it would otherwise have been. They include everyone on the staff of the Bank, as well as the members of the Monetary Policy Committee from 1997 to 2013, the Financial Policy Committee from 2011 to 2013, and the Board of the Prudential Regulation Authority in 2013. Because the Bank is a team, it would be invidious to pick out names, with the exception of one group. As I explain in the Introduction, this is not a memoir. Indeed, the recollections of the crisis that would be of most interest and importance are not those of the principals but of their private secretaries. Through their conversations with opposite numbers in government, at home and abroad, and the private sector, and with a wide range of people inside their own institution, their memoirs would be much more revealing, and dare I say it objective, than those of their bosses. I shall forever be indebted to my private secretaries and economic assistants during my time at the Bank: Alex Brazier, Alex Bowen, Mark Cornelius, Spencer Dale, Phil Evans, Neal Hatch, Andrew Hauser, James Proudman, Chris Salmon, Tim Taylor, Roland Wales, Jan de Vlieghe and Iain de Weymarn. As they move up the ladder in their respective careers, I shall watch with pride and friendship.

I am still asked how I coped with the stress of life at the Bank of England during the crisis. My reply then and now is that stress comes when you lose your job and have the responsibility of a family to support, not when you have a job with the wonderful dedicated and loyal support over many years from my office team including Aishah Aslam, Nikki Bennett, Ian Buggins, Carol Elliott, Alexandra Ellis, Sue Hartnett, Michelle Hersom, Lucy Letts, Michelle Major, Jo Merritt, Nicole Morey, Verina Oxley, Frances Pearce, Vicky Purkiss, Lisa Samwell and Jane Webster. Since leaving the Bank I have been indebted to my personal assistants, Rachel Lawrence in England and Gail Thomas in New York, for replacing that support team.

I am very grateful to both the Stern School of Business and the Law School at New York University for allowing me to join the community of faculty and students, and to participate in the broader intellectual life in that most extraordinary city. It could not have been a better adjustment path to integrate back into civilian life. Robert S. Pirie encouraged and helped to facilitate my spending time in New York. He was a great friend until his sad death in early 2015. He is missed by so many. I am also grateful to the London School of Economics for allowing me to return to a place with happy memories and a most stimulating intellectual atmosphere.

Over the years I have learned an enormous amount from conversations with colleagues in academia and the policy world, many of whom straddled both. They are too numerous to mention, but among those with whom I spoke frequently are Alan Budd, my opposite number in the UK Treasury and then a fellow member of the Monetary Policy Committee; Martin Feldstein, my tutor at Harvard and with his wife Kate friends for over forty years; Stanley Fischer, who as Governor of the Bank of Israel and long-time friend was someone in whom it was possible to confide and discuss; Charles Goodhart, who was co-director with me of the LSE Financial Markets Group for several years and whose knowledge and judgement of central banking is legendary; Otmar Issing, who was the intellectual leader of the European Central Bank during its first critical years; Larry Summers, whose intellectual brilliance and imagination in policy analysis are unmatched; and John Vickers, who followed me as Chief Economist at the Bank of England and under whose chairmanship the Independent Commission on Banking produced a most effective report on the reform of banking in the UK. There are many others, and I can only apologise for not including their names. I have also benefited greatly from conversations over many years with Bernard Connolly, one of the most perceptive writers on the global economy in recent years; Nick Stern, whose friendship both personal and intellectual over many years afforded great support; Adair Turner, who while Chairman of the UK Financial Services Authority worked with me during the crisis and whose ability to produce at speed incisive and innovative reports and books never ceases to amaze me; and not least Martin Wolf, whose books and columns for the Financial Times add up to one of the most important commentaries on our world.

Among those who provided detailed comments on earlier drafts of the manuscript are Alan Budd, Marvin Goodfriend, Otmar Issing, Bethany McLean, Geoffrey Miller, Ed Smith, and graduate students from the Stern School of Business and the Law School at New York University. I also benefited from visits to the University of Chicago, Princeton University, Stanford University and seminars with students at the London School of Economics. Invaluable research assistance was provided by David Low, Diego Daruich and Daniel Katz.